“Darling, I Want My Gay Rights Now” – Why Pride Is More Than a Party

- Words by Peppermint

words HANNAH MCELHINNEY

As World Pride celebrations begin to wind down in Sydney, it’s important to consider the history of Pride and remember the history of LGBTQIA+ rights in Australia. In this extract from Rainbow History Class, Hannah McElhinney reflects on the radical origins of rainbow celebrations.

Today, Pride celebrations occur all over the world and are usually marked by flamboyant dress, dance music, posturing and (eco-friendly) glitter that never leaves your clothes – or your bed sheets. We go to be visible and to celebrate our community, with parties so big they fill stadiums and close down city streets.

It’s heady and intoxicating, but if you were to look closely at the crowd, you might spy an older person in their seventies or even eighties reflecting on the fact that these few hundred thousand strangers have all converged in one place to mark the anniversary of a night they were arrested…

above AUSTRALIAN GAY AND LESBIAN ACTIVISTS AT THE MORNING MARCH HELD ON 24 JUNE 1978 IN COMMEMORATION OF THE STONEWALL UPRISING. LOOK CLOSELY AT THE FLAG IN THE FOREGROUND AND YOU’LL RECOGNISE A PINK INVERTED TRIANGLE. IT MIGHT SEEM PERVERSE THAT THIS NAZI HATE SYMBOL WOULD BE WAVED AROUND BY A YOUNG CHILD AMONG SMILING GAY AND LESBIAN ACTIVISTS, BUT THE PINK TRIANGLE WAS RECLAIMED BY THE COMMUNITY AS A SYMBOL OF RESILIENCE AND IN AUSTRALIA WAS THE PRIMARY SYMBOL OF LGBTQ+ PRIDE UNTIL THE MID-1990S, WHEN THE RAINBOW TOOK OVER.

In Australia, the psychiatry industry said homosexuality should be treated as a mental illness. Homosexual people would still be arrested, but they could often have their sentences reduced or commuted if they submitted to treatment. Such ‘treatments’ would involve aversion therapy – a horrific process where a person would be given drugs to induce nausea and vomiting before being shown photos of their lovers in an attempt to rewire their brain, replacing love with disgust. Sometimes, they resorted to brain surgery.

It’s heady and intoxicating, but if you were to look closely at the crowd, you might spy an older person in their seventies or even eighties reflecting on the fact that these few hundred thousand strangers have all converged in one place to mark the anniversary of a night they were arrested…

Traditional lobotomies had fallen out of favour by then, but psychosurgery was common in the 1970s, particularly if you were a lesbian. Lesbians were often forced to undergo an amygdalotomy, which involved the removal of part or all of the amygdala (a pretty important part of the brain) in order to cure a patient’s attraction. In the early 1970s, one Sydney hospital was responsible for performing two amygdalotomies a week on lesbians, under the knife of a Dr Harry Bailey. To protest Bailey’s butchery of the community, activists dumped a bucket of bloody sheep’s brains in the foyer of his offices.

READ MORE: The Art of Resistance – How Sewing is Stitched into Pride’s History

Activists in Australia were in close contact with their international counterparts, and took inspiration from actions overseas. But solidarity and unity was a given; with just a fraction of the US population, numbers were everything. Members of the gay liberation movement would also be present at women’s demonstrations, anti-war demonstrations and anti-capitalist demonstrations. They were all in it together.

If the movie Mean Girls had been about 1970s activists, one character would have proclaimed, “On Saturdays, we wear combat boots.” Weekly protests were routine for the angry and idealistic, but they were anything but mundane. Demonstrations frequently escalated to police violence and arrests, but also featured dancing and celebration. Gay and lesbian people were determined to match hatred and violence with pride and fun.

In 1978, US-based activists reached out to the international community requesting solidarity action as part of their Christopher Street Liberation Day plans. In Australia, an organisation called Campaign Against Moral Persecution (CAMP) agreed to hold a solidarity protest in Sydney, followed by a celebratory parade.

If the movie Mean Girls had been about 1970s activists, one character would have proclaimed, “On Saturdays, we wear combat boots.”

A permit was issued for the event, the protest went smoothly and the community was looking forward to the evening’s celebration.

But it soon became clear that despite granting a permit for the event, the police were not in the mood to party. They began to urge the parade on, pushing the revellers to move swiftly through the streets of Sydney. Many believe what came next was because the police couldn’t stand the sight of gay and lesbian people celebrating themselves. Peaceful picketing may have been one thing, but pride was a bridge too far.

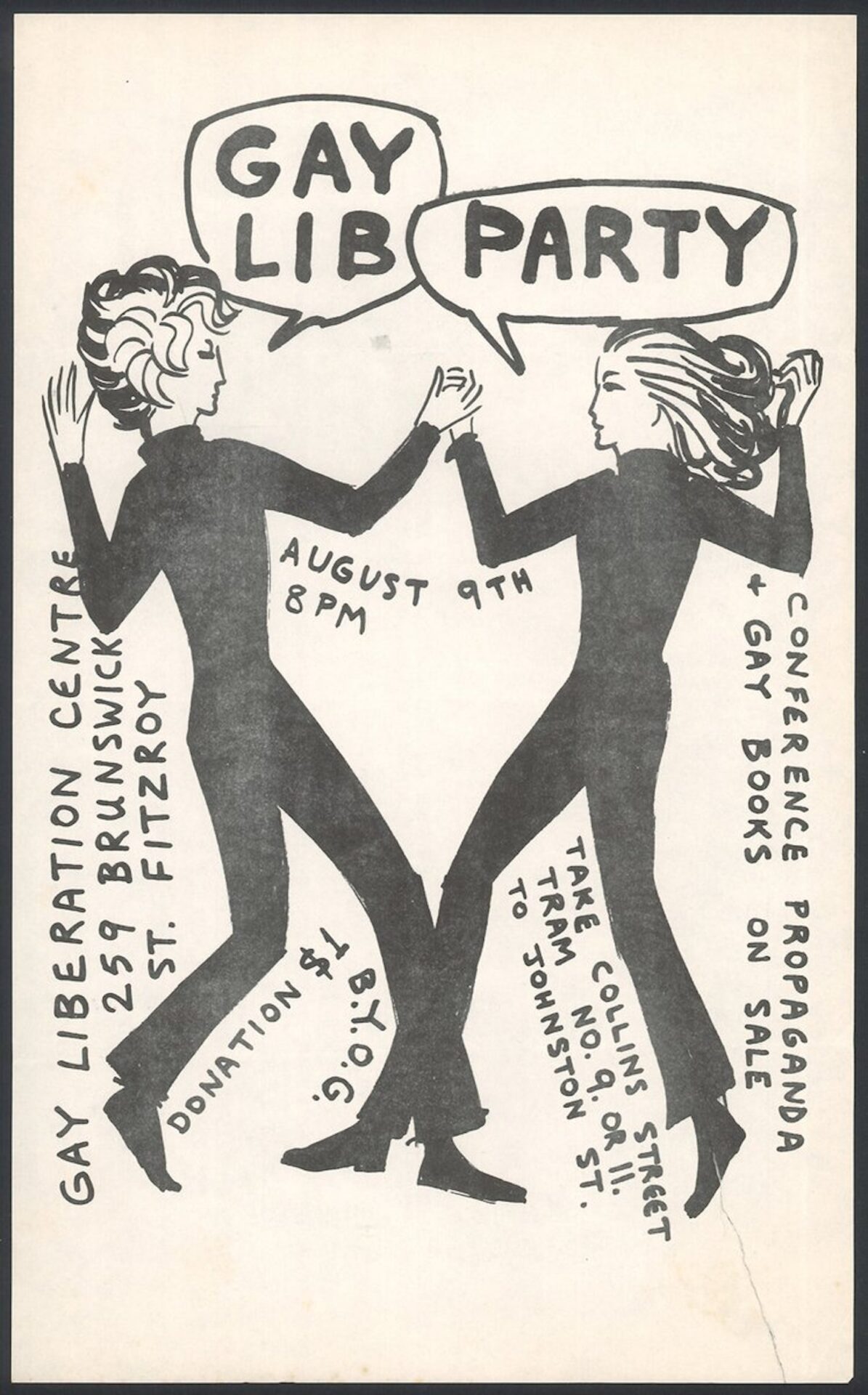

above IN AUSTRALIA, DANCES AND PARTIES BROUGHT ACTIVISTS TOGETHER, BUT POLICE HARASSMENT WAS A FREQUENT OCCURRENCE – AS IT WAS DURING THE EVENT ADVERTISED ON THIS POSTER.

The police confiscated the truck and stereo at the head of the parade, shifting the buoyant mood to one of anger and uncertainty. As the group made their way towards Kings Cross, the police began beating and arresting people. In the ensuing days the media released the names and occupations of all those arrested. Many lost their jobs, their families, their rental tenancies. Some died by suicide.

READ MORE: How to Be a Good Ally All Year Round… Not Just During Pride Month

The cruelty that occurred that night left a vicious scar on the lives of lesbian, bisexual, gay and transgender people in Australia, but it did change something. Just like the Stonewall Uprising stirred the people of New York, the event triggered a stream of protests (and a fair few more arrests) that gathered momentum across Sydney, and eventually resulted in most of the charges being dropped. The following year, the community braced themselves for a repeat of 1978, but their carefully collected bail fund remained untouched. The parade was peaceful and these brave activists celebrated what came to be known as the second Sydney Mardi Gras.

Come Pride season, it’s important to remember who fought for our right to party, but also remember that for queer and trans people, partying will always be political.

The political element of the Sydney Mardi Gras was soon overtaken by the party focus, reflected in the decision to hold future events in summer. After all, a chilly Australian winter didn’t provide much of a backdrop for celebration. The shift drew criticism from some people who believed the event had forsaken its protest roots.

Pride marches around the world have had to contend with this concern – that the radical origins of Pride have been obscured behind the facade of a party. Come Pride season, it’s important to remember who fought for our right to party, but also remember that for queer and trans people, partying will always be political.

This is an edited extract from Rainbow History Class by Hannah McElhinney, published by Hardie Grant Books, RRP $32.99. Available in stores nationally from 8 March.

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Brighten up your inbox with our not-too-frequent emails featuring Peppermint-related news, events, competitions and more!

explore

More articles

It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas…. Which means we are officially entering party season. Work parties, friend-dos, family get-togethers and then we’re straight into New Year festivities. If you’re lucky enough, you might be staring down the barrel…

Look, I don’t want to make anyone panic but IT’S DECEMBER!!! If you’re planning to give homemade gifts, you’re going to have to act fast. …

Furred, feathered, fishy, scaled… The pets we choose are as diverse as our personalities. (And apparently, quite often we resemble each other.) But they all…

When you hang a painting on a wall, the story stays put. But when you wear a beautifully made garment that may as well be…

Hang out with us on Instagram

Any New Year’s resolutions on your list? We love this from @OtterBeeStitching - “be brave enough to suck at something new”.

There’s no points for perfection, but you’ll get a trophy for trying. If nothing else this year, take the leap and try something new.

#OtterBeeStitching #Embroidery #BeBrave #TrySomethingNew #EmbroideryArt

Sunday serving suggestion ☀️

Gorgeous photos from @JolieFemmeStore - who make sweet garments from vintage bedsheets.

#PeppermintMagazine #SlowSunday #SwitchOff #Unplug #ReadAMagazine

A toast to the old you 🥂

We wholeheartedly love this post from the brilliant @EmilyOnLife:

“2026: Reinvent, burn it down, let it go (whatever it is). Year of the Snake it up. Exercise your boundaries, exercise your body, take one teeny step every day towards a life that feels better to be in.

But don’t you dare shit on your old self while you do it.

Hold yourself with reverence and tenderness and respect, because you got you this far. You did your very best with the information and tools you had at the time. You scraped yourself together, you made it work, you survived what felt impossible to survive: again and again and again.

You are perpetually in the process of becoming, whether you can feel it or not, whether or not you add it to your 2026 to-do list.“

Some very wise words from @Damon.Gameau to take us into 2026 🙌🏼

⭐️ We made it!!! ⭐️

Happy New Year, friends. To those who smashed their goals and achieved their dreams, and to those who are crawling over the finish line hoping to never speak of this year again (and everyone else in between): we made it. However you got here is enough. Be proud.

It’s been a tough year for many of us in small business, so here’s to a better year in 2026. We’re forever grateful for all your support and are jumping for joy to still be here bringing you creativity, kindness and community.

We’re also excited to be leaping into the NY with our special release sewing pattern – the Waratah Wrap Dress!

How great are our fabulous models: @Melt.Stitches, @KatieMakesADress and @Tricky.Pockets - and also our incredible Sewing Manager @Laura_The_Maker! 🙌🏼

Ok 2026: let’s do this. 💪🏼

#PeppermintWaratahWrapDress #PeppermintPatterns #SewingPattern #MeMade #WrapDress #WrapDressPattern

Putting together our annual Stitch Up brings on all the feels! We feel humbled that you’ve chosen to sew Peppermint patterns, we feel inspired by the versions you’ve created and we feel proud of you.

Where to begin?! As always, there has been a plethora of Peppermint patterns flooding our feeds this year, and we wish we could showcase more than just a handful of magnificent makes from you, our clever community. We encourage you to flip through the me-made items in your wardrobe or scroll through your grid and remind yourself of the beauty you’ve created with your own two hands (and maybe a seam ripper and some choice words). Congratulations to all of us for our creative achievements this year!

We’ve put together some (but absolutely not all) of our favourites from 2025 over on our website. We hope it inspires your next make!

🪡 Link in bio 🪡

Pictured: @FrocksAndFrouFrou @MazzlesMakes @KatieMakesADress @_Marueli_ @IUsedToBeACurtain @Nanalevine.Couture @PiperInFullColour @MadeByMeJessieB @SarahMalkawi @Made.By.Little.Mama

#PeppermintPatterns #SewingPatterns #MeMade #MeMadeEveryday