Give It Up For Our Glorious Autumn Issue – Out Now!

- Words by Peppermint

Drum roll, please… the richly hued, autumnal beauty that is our latest issue is finally here!

From the resplendent cover – created in collaboration with photographer, illustrator and proud Aboriginal creator Bobbi Lockyer – to the FREE printed pattern nestled within the pages of the mag for the first time ever, you’ll find so many things to inspire you to think, do and make…

We’re as overjoyed as ever to deliver this glorious, lush-paged baby to the world bursting with all the usual considered goodness. It’s the answer to all your pre-snuggle season questions – and a preamble to switching off and settling in for some well-deserved quiet time… In this issue’s pages you’ll dive into an undersea world with a crew of passionate citizen scientists working to rescue the Great Barrier Reef; be inspired by TikTok star and model AJ Clementine as she talks self-acceptance and gender identity; meet the bio-artist collaborating with Mother Nature by growing clothing from grass roots; read about Clothing the Gaps’ journey to freeing the Aboriginal flag; discover how social enterprise Second Stitch is empowering women from diverse backgrounds through the magic of sewing; go behind the seams of Afrofuturistic label Remuse Designs; talk trash about dirt with three local compost champions; discover the secrets of soapmaking with Washpool Skin Wellness; colour yourself happy with queen of chaotic, joyful hues Katie Kortman; and laugh as we try switching off from social media for a week.

Plus you’ll meet the founder of the #MeMadeMay movement; get making a cute DIY (and pattern-free) bucket hat; learn from artist and activist Brenna Quinlan who draws to inspire action; embrace the cosy art of hygge – minus the commercialism; bite into a sweeter tomorrow thanks to Fairtrade chocolate; waddle to the little town of Penguin, Tasmania; lean into the leaf trend with a curation of botanical beauties; plus cook with Indigenous chef Nornie Bero who brings big island vibes to Australian pantries with native ingredients! And for those in the back row: the free pattern is in the issue!

Get your copy today by visiting our shop or your closest stockist (and for the digital version, head here).

Take a peek inside this issue!

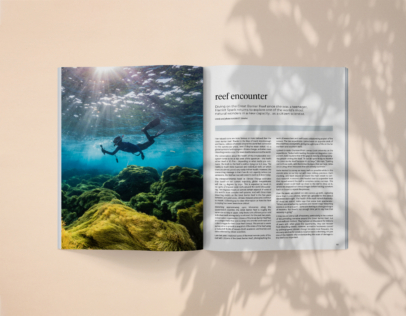

‘REEF ENCOUNTER’ Diving on the Great Barrier Reef since she was a teenager, Harriet Spark returns to explore one of the world’s most natural wonders in a new capacity… as a citizen scientist. Words and photos by Harriet Spark.

Few natural icons are more famous or more beloved than the Great Barrier Reef. Thanks to the likes of David Attenborough and Nemo, millions of people around the world feel connected to this spectacular place, even if they’ve never visited. It’s a global symbol of anthropogenic climate change, and when mass bleaching events occur, the news reverberates across the world.

The conversation about the health of this irreplaceable ecosystem tends to be at two ends of the spectrum – the Reef’s either dead or it’s fine – depending on what media you consume. The truth is, the Reef is neither dying nor is it okay. The reality is much more nuanced and individual reefs (of which there are almost 3000) vary vastly in their health. However, the overarching message is that if we do not urgently reduce our emissions, the Reef we love will cease to exist as it does today.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that based on our current trajectory, global temperatures will rise 1.5 degrees by 2030. This is expected to result in 70–90% of tropical coral reefs around the world disappearing. Two degrees means an almost certain wipeout of some of the world’s most complex reef systems. And with three mass bleaching events on the Great Barrier Reef in the five years between 2015 and 2020, climate-induced pressures continue to mount. Collecting up-to-date information on how the Reef is coping has never been more critical.

‘MIND THE GAP’ Just two years into its life, Aboriginal social enterprise and ethical fashion brand Clothing the Gaps is at the forefront of making real, lasting change for some of Australia’s most important national conversations. Words by Nick Harvey-Doyle

We all love clothes that make us feel good. In reaching for something that both celebrates our bodies and reflects our personalities, we often make a silent yet illustrative statement about who we are. But in a world where virtue signalling and value washing is rife, can our clothes reach deeper and create real change? Aboriginal social enterprise and fashion brand Clothing The Gaps (CTG) is proving its case – socially and legally – from a buzzing retail and distribution space on Wurundjeri Country in Brunswick, Victoria.

In a world where virtue signalling and value washing is rife, can our clothes reach deeper and create real change?

Already facing multiple legal battles in its short life, CTG’s fashion – which includes bold streetwear apparel featuring Aboriginal designs and messages – is the gateway to “bringing people into the conversation and engaging with content that they perhaps didn’t get taught at school,” says Sarah Sheridan, one of the brand’s co-founders. Created together with Gunditjmara woman Laura Thompson, the brand is on a mission to influence social change for First Nations peoples and communities, encouraging all Australians to wear their values on their tees.

Since both co-founders have backgrounds in health, the fashion industry might seem an unexpected realm for them to have landed in. Having first crossed paths working at the Victorian Aboriginal Health Service (VAHS) in 2014, Laura and Sarah developed a strong connection while delivering preventative health care programs in Aboriginal communities – an experience that shaped the social enterprise they oversee today.

‘MATERIAL GIRL’ Changing the way we think about waste, and its potential for inspiration and creation, is both a life’s calling and an obsession for inventor and materials scientist Professor Veena Sahajwalla. Words by Lauren Baxter.

“I love that scientific challenge that asks, ‘If it no longer can be used as a piece of clothing or if it’s a broken bit of glass, but your town or the town next door doesn’t have a smelter, what else can you do with it?’” she enthuses. “Our solution, in the case of green ceramics, was a complete game changer in that we’ve actually shown that you don’t need to smelt glass to make that product. So it’s also about then challenging the notion that this is how traditional, conventional manufacturing is done. And what we’re saying is, ‘No, actually if you were doing it in a microfactory, you could do it in a completely different way.’ Because it all comes down to how you manufacture and for what purpose.”

These microfactories are intended to be used in the real world to produce these products in real time, turning consumer waste into commercially viable products and creating local jobs. The premise is to set them up alongside disposal centres and process the waste at the source, reducing carbon miles. “It was always about performance and quality of the product. The assumption that everything has to be mass-scaled and mass-produced to make money is what I wanted to show is not necessarily right,” Veena says. “Importantly,” she continues, “[the microfactories] only make as much as we need. You can literally get it in micro time and micro batches.”

On-the-ground, practical solutions that anybody in the world can deploy have always been Veena’s motivation.

“In my mind, waste shouldn’t be seen as waste,” she explains. “It’s a resource. But it only becomes a resource when it can actually come back to life as a manufactured product. And when we think about circular manufacturing, it’s not just one circular loop. It’s multiple circularity solutions.”

It brings into question how we view waste in the first place. “Growing up in a place like Mumbai, it was always about, to some extent, appreciating what you had because there was a sentimental value attached to it,” Veena reflects. “I remember the story of every piece of clothing that I got, and some things I still hang on to because they were from days when I was a student. There’s a photo of me wearing this t-shirt that I have in one of my albums. And the fact that it’s still hanging in my wardrobe, I mean, that’s the stuff that, I think, for all of us is important.”

“In my mind, waste shouldn’t be seen as waste. It’s a resource. But it only becomes a resource when it can actually come back to life as a manufactured product.”

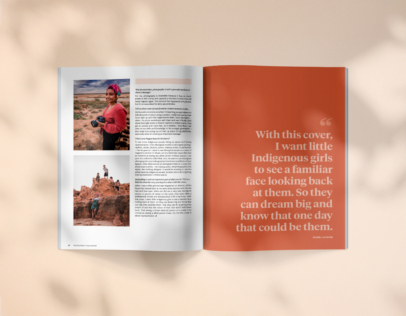

‘A SHIFTING LENS’ Last year’s NAIDOC Artist of the Year, Ngarluma, Kariyarra, Nyulnyul and Yawuru photographer and illustrator Bobbi Lockyer is the creative behind our autumnal, richly hued cover.

Why do you believe photography is such a powerful medium to share a message?

For me, photography is incredible because it has so much power to tell a story and captures a moment in time that will never happen again. The moment has happened and passed, but it’s encapsulated for all to see and relive.

Tell us about some of your favourite creative moments so far…

My favourite moments are when I’m teaching young Indigenous kids about art or about using a camera. I really love seeing their faces light up and their eagerness to learn. Even teenagers – when I do photo workshops with them and see it finally click about how light works or how to capture a certain scene, they get so excited and I love that. As a creative, I love that I can pass on my skills and knowledge to the younger generation. I also really love seeing my art take up space on big platforms, especially when it’s sharing an important message.

What’s your biggest hope for the future?

To see more Indigenous people taking up space and having representation. From Aboriginal models to Aboriginal photographers, artists, doctors, actors, makeup artists, in parliament – the list goes on. I want to see Aboriginal people on covers of magazines and on TV shows, not as a tokenistic space filler but as common as seeing any white person in those spaces. I am part of a collective called Blak Lens; we want to see Aboriginal photographers and videographers hired and amplified in these spaces. Often when we see an Aboriginal model on a cover, the whole team is white – the makeup artist, the photographer, the stylist, the clothing designer. It would be amazing to see the whole team be Indigenous as well. So Blak Lens is about getting that representation in these spaces.

‘STITCHED TOGETHER’ Empowering women from diverse backgrounds both economically and socially, Melbourne’s Second Stitch harnesses the magic of sewing to stitch together a community. Words by Mireille Stahle.

Jaffna Tamil refugee Mary graduated from the certificate program which, in addition to her 15 years of tailoring experience, gave her the confidence to start her own baby clothing business.

“They were so supportive of my learning,” says Mary, who continues to work at the studio to stay connected to the community and practise speaking English.

For Rohini, also a Tamil refugee, the highlight of working at Second Stitch is the strong community focus. “I have been making my own clothes and clothes for my family since I was 12 years old,” she explains. “I escaped war with my son, and I struggled as a single mother with very little English. I love working with the community – we share skills, but also take care of each other. When I wake up in the morning, I’m excited to see my friends at Second Stitch.”

Rohini’s favourite part of work is meeting customers to discuss their alterations. “Talking to customers is how I’ve learned how to speak English!” she says proudly. “I love alterations because I love chatting to the customers.”

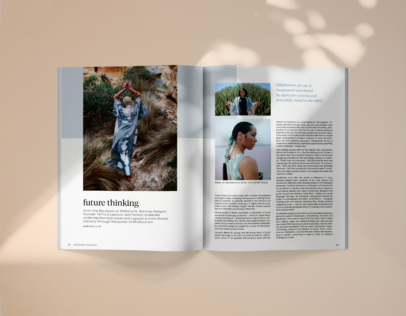

‘FUTURE THINKING’ From the Big Apple to Melbourne, Remuse Designs’ founder Tamara Leacock uses fashion to elevate underrepresented voices and support a more diverse industry through the power of Afrofuturism. Words by Emily Lush

Folds of linen and cotton ripple with a mosaic of eucalyptus and organic indigo, emulating cresting waves or shifting dunes. With an aesthetic so perfectly attuned to the contours and colours of the Australian landscape, it might come as a surprise to learn that Remuse Designs’ founder Tamara Leacock was born and bred a world away in New York.

Having worked in fashion journalism, in wholesale, on trade shows and in backstage production – in the UK, South Africa, Jamaica and beyond – Tamara has had an opportunity to contemplate the industry from almost every angle throughout her career. Yet as a creative director, her drive towards sustainability and ethical design isn’t guided by a sense of disenchantment, but rather by divine forces.

“Afrofuturism, for me, is imagination untethered by oppressive systems and powerfully rooted in the stars.”

Tamara’s affinity for ecology and the strong sense of social justice she brings to her work can both be traced to Afrofuturism, which is “an aesthetic that positions space and the cosmos as inspiration for social liberation,” she explains. Primarily expressed through music and art (and perhaps most commonly associated with the 2018 film Black Panther), Afrofuturism is a movement that has its roots in African diasporic experience, though the term was coined in the US in the 1990s. It harnesses technoculture and fantastical elements to inspire Black communities to imagine solutions to very real problems born from systemic oppression. “Afrofuturism, for me, is imagination untethered by oppressive systems and powerfully rooted in the stars,” Tamara says.

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Brighten up your inbox with our not-too-frequent emails featuring Peppermint-related news, events, competitions and more!

explore

More articles

Look, I don’t want to make anyone panic but IT’S DECEMBER!!! If you’re planning to give homemade gifts, you’re going to have to act fast. …

Hang out with us on Instagram

“In the 1940’s, Norwegians made and wore red pointed hats with a tassel as a form of visual protest against Nazi occupation of their country. Within two years, the Nazis made these protest hats illegal and punishable by law to wear, make, or distribute. As purveyors of traditional craft, we felt it appropriate to revisit this design.”

Crafters have often been at the heart of many protest movements, often serving as a powerful means of political expression. @NeedleAndSkein, a yarn store in Minnesota, are helping to mobilise the craftivists of the world with a ‘Melt The Ice’ knitting pattern created by @Yarn_Cult (with a crochet pattern too), as a way of peaceful protest.

The proceeds from the $5 pattern will go to local immigrant aid organisations – or you can donate without buying the pattern.

Raise those needles, folks – art and craft can change the world. 🧶

Link in bio for the pattern.

Images: @Gather_Fiber @NeedleAndSkein @a2ina2 @KyraGiggles Sandi.204 @WhatTracyMakes AllieKnitsAway Auntabwi2

#MeltTheIce #Craftivism #Knitting #CraftForChange

TWO WEEKS TO GO! 🤩

"The most important shift is moving from volume-led buying to value-led curation – choosing fewer, better products with strong ethics, considered production and meaningful stories. Retailers have real influence here: what you buy signals what you stand for. At Life Instyle, this means using the event to discover and invest in small-scale, planet-considerate brands that align with your values and your customer’s conscience. Consumers don’t need more things; they need better things, and retailers play a key role in selecting, contextualising, and championing why those products matter."

Only two more weeks until @Life_Instyle – Australia`s leading boutique retail trade show. If you own a store, don`t miss this event! Connect with designers, source exquisite – and mindful – products, and see firsthand why this is Australia’s go-to trade show for creatives and retailers alike. And it`s free! ✨️

Life Instyle – Sydney/Eora Country

14-17 February 2026

ICC, Darling Harbour

Photos: @Samsette

#LifeInstyle #SustainableShopping #SustainableShop #RetailTradeEvent

Calling all sewists! 📞

Have you made the Peppermint Waratah Wrap Dress yet? Call *1800 I NEED THIS NOW to get making!

This gorgeous green number was modelled (and made) by the fabulous Lisa of @Tricky.Pockets 🙌🏼

If you need a nudge, @ePrintOnline are offering Peppermint sewists a huge 🌟 30% off ALL A0 printing 🌟 when you purchase the Special Release Waratah Wrap Dress pattern – how generous is that?!

Head to the link in bio now 📞

*Not a real number in case that wasn`t clear 😂

#PeppermintWaratahWrapDress #PeppermintPatterns #SewingPattern #WrapDress #WrapDressPattern

8 Things to Know About January 26 - from @ClothingTheGaps:

Before you celebrate, take the time to learn the truth. January 26 is not a day of unity it’s a Day of Mourning and Survival for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It marks the beginning of invasion, dispossession, and ongoing colonial violence. It’s time for truth-telling, not whitewashed history.

Stand in solidarity. Learn. Reflect. Act.

✊🏽 Blog written by Yorta Yorta woman Taneshia Atkinson.

🔗 Link in bio of @ClothingTheGaps to read the full blog

#ChangeTheDate #InvasionDay #SurvivalDay #AlwaysWasAlwaysWillBe #ClothingTheGaps

As the world careens towards AI seeping into our feeds, finds and even friend-zones, it`s becoming increasingly hard to ignore.

We just wanted to say that here at Peppermint, we are choosing to not print or publish AI-generated art, photos, words, videos or content.

Merriam-Webster’s human editors chose `slop` as the 2025 Word of the Year – they define it as “digital content of low quality that is produced usually in quantity by means of artificial intelligence.” The problem is, as AI increases in quality, it`s becoming more and more difficult to ascertain what`s real and what`s not.

Let`s be clear here, AI absolutely has its place in science, in climate modelling, in medical breakthroughs, in many places... but not in replacing the work of artists, writers and creatives.

Can we guarantee that everything we publish is AI-free? Honestly, not really. We know we are not using it to create content, but we are also relying on the artists, makers and contributors we work with, as well as our advertisers, to supply imagery, artwork or words created by humans. AI features are also creeping into programs and apps too, making it difficult to navigate. But we will do our best to avoid it and make a stand for the artists and creatives who have had their work stolen and used to train AI machines, and those who are now losing work as they are replaced by this energy-sapping, environment-destroying magic wand.

Could using it help our productivity and bottom line? Sure. And as a small business in a difficult landscape, that`s a hard one to turn down. We know other publishers who use AI to write stories, create recipes, produce photo shoots... but this one is important to us.

`Touch grass` was also a Merriam-Webster Word of the Year. We`ll happily stick with that as a theme, thanks very much. 🌿

If your fingers are twitching for some crafting, take a peep at this massive list of marvellous makes that can be whipped up in a flash, put together by our Sewing Manager Laura. Ok yes, it was originally a roundup we created for easy Christmas gifts, but now it can be your blueprint for easy craft wins to go on your 2026 making must-do list!

If money and time are slim for you right now – as they are for many of us – these 22 projects will help you avoid the chaos and consumerism of the malls, scratch that creative itch and produce a fun me-made make that won’t break the bank.

Link in bio! 🪡🎨✂️

#PeppermintMagazine #MeMadeGifts #DIYs #EasyWins