Come Out and Play… Peppermint Issue 58 is Here to Make Your Day!

- Words by Peppermint

words LAUREN BAXTER, EDITOR

Football has always been a big part of my life. However, a ruptured ACL a few years back took me out of the game. With a knee reconstruction and rehabilitation, I was back on my feet, but, as I’m sure you will empathise, life gets busy and my boots sat gathering dust in the garage. This year, for one reason or another, I felt compelled to get back on the pitch. And the simple joy of gathering with mates, both new and old, a few times a week to kick a ball has reminded me of the importance of engaging with a ‘third place’.

Coined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg in the 1980s, a ‘third place’ refers to the social surroundings that are separate from the usual environments of home and work. A place of conversation and connection while sharing common ground. They, as Ray describes, are “anchors of community life and facilitate and foster broader, more creative interaction”. Indeed as we as a society become more and more isolated, it seems to me the ‘third place’ could be an antidote to civic disengagement.

My hope for Peppermint is that it too acts as a sort of third place. A place to turn when the weight of the world hangs heavy and a reminder of the importance, and comfort, of community.

That feeling of comfort, I hope you’ll find, is stitched into every page of our new issue, which should be in your hot little hands very soon. We go behind the seams with Cardigang and break the sweater curse with a generational tale of love and knitting. We return to slow, artisanal principles as we ponder the future of retail. We embrace the pleasures of leisure and go green beyond the grave. We bake vegan pies and walk with the giants of the forest alongside Bob Brown. And, I’m so very pleased to say, we meet a whole lotta animals that are back from the brink of extinction.

My hope for Peppermint is that it too acts as a sort of third place. A place to turn when the weight of the world hangs heavy and a reminder of the importance, and comfort, of community.

I hope you’ll see this new issue as an invitation to take a moment for yourself. It is a reminder that we must continue showing up – for ourselves, for one another, for the planet – to broaden and strengthen our sense of community: whether that’s chatting with a stranger, sharing a me-made make on Instagram or lacing up your boots.

Happy reading,

Lauren x

Subscribe (and never miss an issue).

Take a peek inside this issue!

‘SEW TO GROW’ Our editor has a secret… she doesn’t know how to sew. Words by Lauren Baxter.

“But I’m going to learn.” It was a commitment I made with verve – boldly, and hiding the slight embarrassment I felt to be almost 30 without the basic know-how to mend a loose button.

Despite many opportunities, I never picked up the ol’ needle and thread. Textiles had been an elective at school – I preferred to spend home economics in the kitchen making, and then eating, lemon meringue pie. My great-grandmother was a seamstress during the war – sadly, no wholesome matriarchal-learning stories here. Hell, I even work at Peppermint – the home of style, sustainability, substance and sewing! One could argue it was a classic case of millennial ennui. That I had the privilege of financial security and could afford a tailor to hem my pants. There was most definitely a disdain for ‘traditional’ gender roles. Perhaps, too, a broader cognitive dissonance because of the disconnect I felt with the people who made my clothes.

Dropping its dowdy hobbyist image, the home sewing movement has shifted to become something that is considered thoroughly modern, sustainably minded and socially gratifying. Craft, in general, feels cool.

Recent years, however, have seen a groundswell in all things me-made – spurred on by lockdowns, spending time at home and a growing cultural awareness of the true cost of fashion. Dropping its dowdy hobbyist image, the home sewing movement has shifted to become something that is considered thoroughly modern, sustainably minded and socially gratifying. Craft, in general, feels cool.

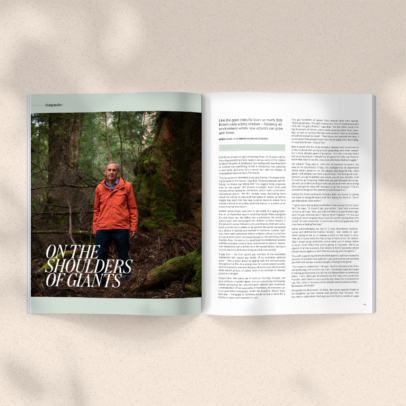

‘ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS’ Like the giant trees he loves so much, Bob Brown casts a long shadow – fostering an environment where new activists can grow and thrive. Words by Bonnie Liston.

Bob Brown shows no signs of slowing down. At 78 years old, he has a bag packed and tent ready to set up camp in the Tarkine to block the path of bulldozers; he’s sailing with Sea Shepherd to combat the overfishing of krill in Antarctica; he’s planning a new book; and now, he’s a movie star with the release of biographical documentary The Giants.

The film reveals many fascinating facts about the nature of trees and their place in nature, as well as insight into Bob’s life that may surprise those to whom he is merely a fixture in Australia’s political history, or a name on an environmental foundation.

“I’m not so much interested in my past history; I’m always looking forward to the future,” says Bob. Characteristically self-effacing, he shares top billing with “the biggest living creatures ever on the planet”, the ancient eucalypts, huon pines and myrtles of the Tasmanian rainforests, which make up the other eponymous giants. The film reveals many fascinating facts about the nature of trees and their place in nature, as well as insight into Bob’s life that may surprise those to whom he is merely a fixture in Australia’s political history, or a name on an environmental foundation.

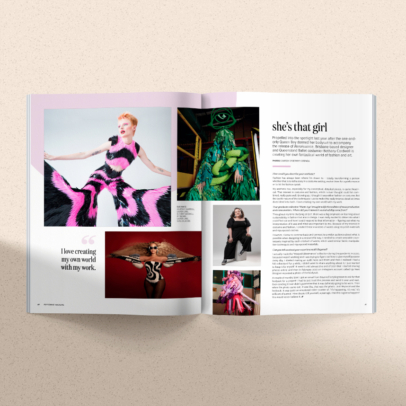

‘THE GIRL AND THE ROBOT’ Artificial intelligence is all over the news. And it’s raising serious questions about art, ethics and our future. So what does AI mean for creativity? Words by Nirrimi Firebrace.

It makes sense that artists feel threatened. Committing to a creative process takes dedication. When you pour yourself into your work, it becomes a part of you, and sharing those parts of yourself means facing vulnerability and risk. To reduce the process to a string of words and a soulless machine feels both sacrilegious and unfair.

As a photographer, I’ve sacrificed sleep for time to work and groceries to afford the expensive equipment I needed. I’ve had my photography stolen by global fashion brands and never received a credit or a cent. My creative techniques and body of work took years to build; AI can do it all in mere seconds. I imagine almost every creative is feeling at least slightly threatened.

To reduce the process to a string of words and a soulless machine feels both sacrilegious and unfair.

But this feeling isn’t new. When photography gained popularity, the painter Paul Delaroche famously declared, “From today, painting is dead.” There were debates over whether it could even be considered an art form. Next to painting, the act of pressing a button on a machine and calling the instant images “art” must have seemed mechanical, lazy and devoid of creative depth. There is no longer any debate that photography is art, but AI-generated art is stirring up similar fears and challenging our preconceptions.

‘BEYOND THE BINARY’ As anti-trans rhetoric runs rife both online and off, award-winning author and trans educator Nevo Zisin (they/them) explores what creating a liberated society beyond gender binaries might look like. Words by Nevo Zisin.

Gender is a bit like clothing – some of us are very intentional with the clothes we wear. We have a lot of identity wrapped up in them. We think about aesthetics and design. Others treat clothes mechanically: “What can I put on my flesh prison today?”

Once you start to pull the threads of the things people feel are objective – the things people feel are entirely stable – everything begins to unravel.

Similar to clothing, we have normalised gender conformity in our modern lives. Because we have normalised the gender binary so deeply, we don’t even realise that we are performing gender. We don’t realise that we are subscribing to gender norms. We don’t see things such as going to the gym as being a form of gender-normative subscription for men. We don’t see getting Botox, getting a labiaplasty, getting hair replacement therapy, doing our makeup or choosing our clothing as performances of gender. We invisibilise and create a default of a certain kind of existence.

Now, when I say a performance of gender, I’m not putting a judgement statement on it. There’s nothing judgmental about that. It just purely is. But once you start to pull the threads of the things people feel are objective – the things people feel are entirely stable – everything begins to unravel.

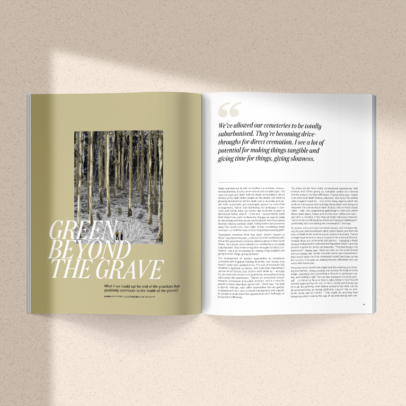

‘GREEN BEYOND THE GRAVE’ What if we could opt for end-of-life practices that positively contribute to the health of the planet? Words by Linsey Rendell.

Death and what we do with our bodies is a universal, environmental dilemma. It’s also an emotional and complex topic. The ways we approach death and the rituals surrounding it are as diverse as the eight billion people on this planet. But there’s a growing movement to rethink death care in Australia and create more sustainable and meaningful options for end-of-life arrangements. Rather than blanketing the landscape in concrete and marble while our bodies take hundreds of years to decompose below, what if – in the end – we put Mother Earth first? What if we could combine the changes we need to make for the climate with how we are memorialised? And if the current funerary industry sanitises death, hiding bodies and processes away from loved ones, how might closely considering death care open up healthier ways of mourning and processing grief?

We’ve allowed our cemeteries to be totally suburbanised. They’re becoming drive-throughs for direct cremation. I see a lot of potential for making things tangible and giving time for things, giving slowness.

“Australians somehow think that death doesn’t happen to them,” says David Neustein, a director at Other Architects who sits on the government cemetery advisory group in New South Wales. “As a result, we’ve allowed our cemeteries to be totally suburbanised. They’re becoming drive-throughs for direct cremation. I see a lot of potential for making things tangible and giving time for things, giving slowness.”

‘CLOSE-KNIT FRIENDS’ Started as a way to busy idle hands and minds during lockdown, knitting has quickly become a raison d’être for besties Cat Bloxsom and Morgan Collins of Cardigang. Words by Mireille Stahle.

Morgan Collins and Cat Bloxsom jokingly describe their friendship as forged over many lifetimes. They met while working in insurance marketing – not the first career one might envisage for the brains behind Melbourne-based cult knitting brand, Cardigang.

“In our corporate careers, we felt as if we were running a rat race, working towards a goal that wasn’t necessarily personal,” says Morgan. Then came the game-changer that absolutely nobody asked for – COVID-19.

More than just busying idle hands, the act of knitting brought Cat and Morgan a sense of calm and wellbeing, and they wanted to tell the world.

Like many long-suffering Melburnians, Cat and Morgan were bored, anxious and looking for a way to alleviate rising stress levels during lockdowns. No longer working together, Cat explains they “needed a way to stay connected”.

Armed with YouTube and a vision of wrapping themselves in something bright and fluffy, the pair dove headfirst into knitting jumpers. “I’m certainly not great in the kitchen, and everyone was doing sourdough,” says Cat. “We wanted something we could do that we could actually keep and use after making it.” More than just busying idle hands, the act of knitting brought Cat and Morgan a sense of calm and wellbeing, and they wanted to tell the world.

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Brighten up your inbox with our not-too-frequent emails featuring Peppermint-related news, events, competitions and more!

explore

More articles

Look, I don’t want to make anyone panic but IT’S DECEMBER!!! If you’re planning to give homemade gifts, you’re going to have to act fast. …

Hang out with us on Instagram

🌻 The Paddington 🌻

This is a much-loved staple, created for Issue 50 in 2021. We love seeing the #PeppermintPaddingtonTop continually popping up in our feeds!

How stunning is our model Elon MelaninGoddessEfon – she told us it was one of the first times she had been asked to come to a shoot with her natural hair. 🌻

We worked with South African patternmaker Sarah Steenkamp of @FrenchNavyNow_ to create this wardrobe essential – the perfect puff-sleeve blouse. Raglan sleeves make it the ultimate beginner sew, plus the gorgeous back buttons let you add your own personal twist.

Pattern via the link in bio! 🪡

Photos: @KelleySheenan

Fabric: @Spoonflower

Model: MelaninGoddessEfon

“In the 1940’s, Norwegians made and wore red pointed hats with a tassel as a form of visual protest against Nazi occupation of their country. Within two years, the Nazis made these protest hats illegal and punishable by law to wear, make, or distribute. As purveyors of traditional craft, we felt it appropriate to revisit this design.”

Crafters have often been at the heart of many protest movements, often serving as a powerful means of political expression. @NeedleAndSkein, a yarn store in Minnesota, are helping to mobilise the craftivists of the world with a ‘Melt The Ice’ knitting pattern created by @Yarn_Cult (with a crochet pattern too), as a way of peaceful protest.

The proceeds from the $5 pattern will go to local immigrant aid organisations – or you can donate without buying the pattern.

Raise those needles, folks – art and craft can change the world. 🧶

Link in bio for the pattern.

Images: @Gather_Fiber @NeedleAndSkein @a2ina2 @KyraGiggles Sandi.204 @WhatTracyMakes AllieKnitsAway Auntabwi2

#MeltTheIce #Craftivism #Knitting #CraftForChange

TWO WEEKS TO GO! 🤩

"The most important shift is moving from volume-led buying to value-led curation – choosing fewer, better products with strong ethics, considered production and meaningful stories. Retailers have real influence here: what you buy signals what you stand for. At Life Instyle, this means using the event to discover and invest in small-scale, planet-considerate brands that align with your values and your customer’s conscience. Consumers don’t need more things; they need better things, and retailers play a key role in selecting, contextualising, and championing why those products matter."

Only two more weeks until @Life_Instyle – Australia`s leading boutique retail trade show. If you own a store, don`t miss this event! Connect with designers, source exquisite – and mindful – products, and see firsthand why this is Australia’s go-to trade show for creatives and retailers alike. And it`s free! ✨️

Life Instyle – Sydney/Eora Country

14-17 February 2026

ICC, Darling Harbour

Photos: @Samsette

#LifeInstyle #SustainableShopping #SustainableShop #RetailTradeEvent

Calling all sewists! 📞

Have you made the Peppermint Waratah Wrap Dress yet? Call *1800 I NEED THIS NOW to get making!

This gorgeous green number was modelled (and made) by the fabulous Lisa of @Tricky.Pockets 🙌🏼

If you need a nudge, @ePrintOnline are offering Peppermint sewists a huge 🌟 30% off ALL A0 printing 🌟 when you purchase the Special Release Waratah Wrap Dress pattern – how generous is that?!

Head to the link in bio now 📞

*Not a real number in case that wasn`t clear 😂

#PeppermintWaratahWrapDress #PeppermintPatterns #SewingPattern #WrapDress #WrapDressPattern

8 Things to Know About January 26 - from @ClothingTheGaps:

Before you celebrate, take the time to learn the truth. January 26 is not a day of unity it’s a Day of Mourning and Survival for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It marks the beginning of invasion, dispossession, and ongoing colonial violence. It’s time for truth-telling, not whitewashed history.

Stand in solidarity. Learn. Reflect. Act.

✊🏽 Blog written by Yorta Yorta woman Taneshia Atkinson.

🔗 Link in bio of @ClothingTheGaps to read the full blog

#ChangeTheDate #InvasionDay #SurvivalDay #AlwaysWasAlwaysWillBe #ClothingTheGaps

As the world careens towards AI seeping into our feeds, finds and even friend-zones, it`s becoming increasingly hard to ignore.

We just wanted to say that here at Peppermint, we are choosing to not print or publish AI-generated art, photos, words, videos or content.

Merriam-Webster’s human editors chose `slop` as the 2025 Word of the Year – they define it as “digital content of low quality that is produced usually in quantity by means of artificial intelligence.” The problem is, as AI increases in quality, it`s becoming more and more difficult to ascertain what`s real and what`s not.

Let`s be clear here, AI absolutely has its place in science, in climate modelling, in medical breakthroughs, in many places... but not in replacing the work of artists, writers and creatives.

Can we guarantee that everything we publish is AI-free? Honestly, not really. We know we are not using it to create content, but we are also relying on the artists, makers and contributors we work with, as well as our advertisers, to supply imagery, artwork or words created by humans. AI features are also creeping into programs and apps too, making it difficult to navigate. But we will do our best to avoid it and make a stand for the artists and creatives who have had their work stolen and used to train AI machines, and those who are now losing work as they are replaced by this energy-sapping, environment-destroying magic wand.

Could using it help our productivity and bottom line? Sure. And as a small business in a difficult landscape, that`s a hard one to turn down. We know other publishers who use AI to write stories, create recipes, produce photo shoots... but this one is important to us.

`Touch grass` was also a Merriam-Webster Word of the Year. We`ll happily stick with that as a theme, thanks very much. 🌿