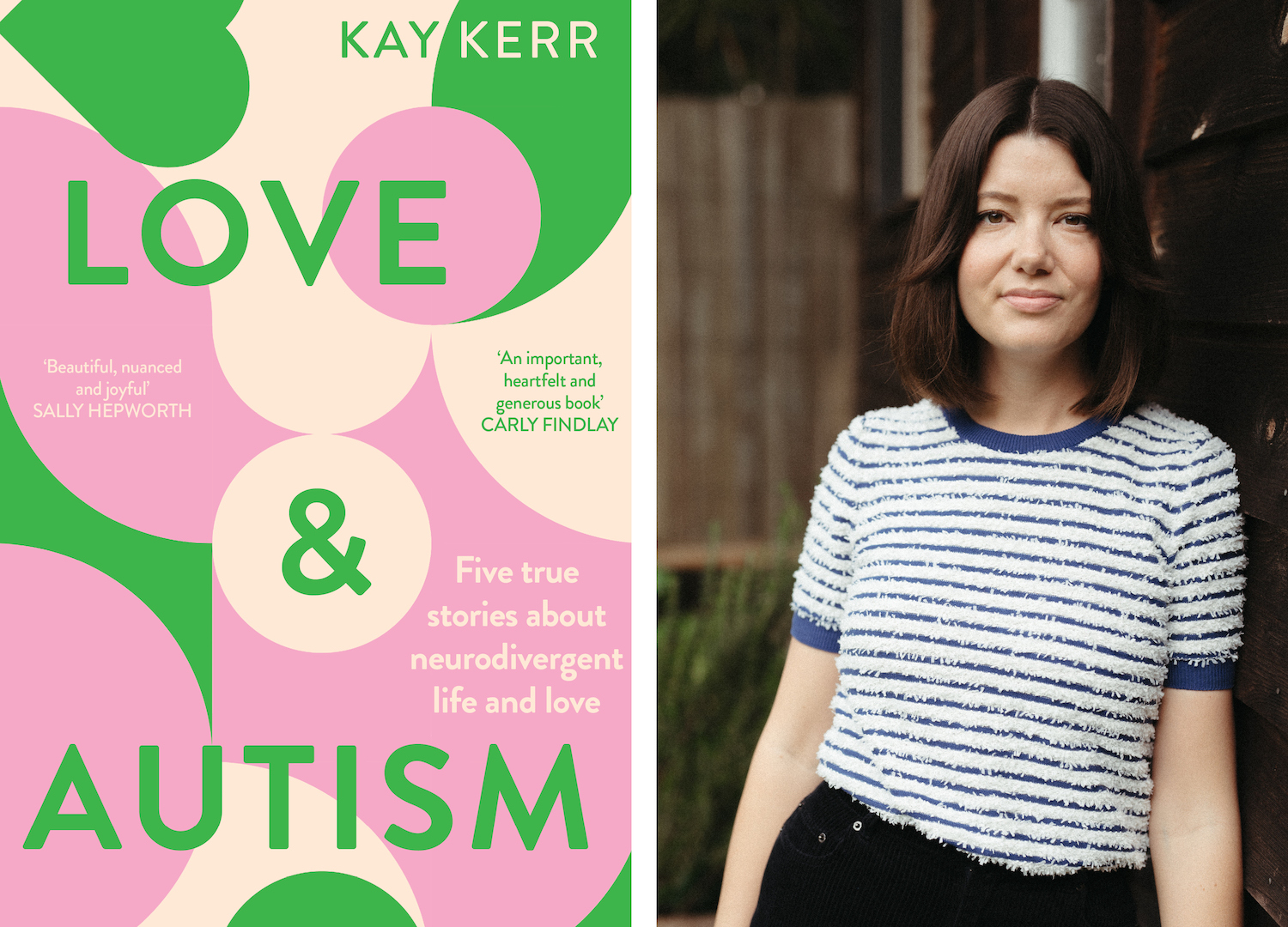

“The Knowledge Felt Revolutionary”: Kay Kerr on Love and Autism

words KAY KERR photos JESS KEARNEY

“Why are eye contact and ‘I love you’ considered the markers of love in Western culture?” It’s a question posed by autistic author and journalist Kay Kerr in her latest book, Love and Autism. Indeed when you consider broad, mainstream conversation regarding neurodivergent people, it’s fair to say our understanding of autism remains limited. But through her work, Kay sets out to bridge this gap by exploring the commonality of love – in all its forms.

Hello there. As you have no doubt gathered by now, I am Kay and I am an autistic writer. I have always been autistic, and, bar a couple of years at the start there, I suppose I have always been a writer as well. Or, more accurately, I have always been obsessed with stories. And books. Books, books, glorious books. Books don’t call you poor for having the wrong sneakers on sports day, and books would never dump you over MSN Messenger right before you have to start a shift at McDonald’s, forcing you to spend four hours mixing entirely too many McFlurrys and serving them with tears streaming down your face. No, books are the best. And the best books, to me, are the ones that explore ideas around or teach me something about love.

Love has always intrigued me, in part because I have carried for a long time a feeling that I am doing love wrong. I am not emotional enough in the ways people expect, and too emotional in ways they do not like to see. My tears come too late, and never for the right reasons. The McFlurry tears weren’t even about the boy; they were born of sheer frustration at having a choice (to be in a teen relationship or not) taken out of my hands. Knowing how things are going to go has always been important – too important, some would say. I don’t ask the right questions or care about the right things. I don’t thank people as much as they seem to want to be thanked. I like to be alone a lot more than other people, and I need things to be a certain way. How I feel in the moment is so big it often convinces me this is how I will feel forever. And that goes for all kinds of love. I have felt like the wrong kind of daughter, the wrong kind of sister and the wrong kind of friend. My mouth and my moods have got me in all kinds of trouble. Sensory processing distress can present as anger, and a meltdown can look a lot like rage. My direct communication style has embarrassed my mother in precarious social situations, like when a set of my Enid Blyton books were returned full of scribbles. “It’s fine,” she assured them. “It’s definitely not,” I raged.

How I feel in the moment is so big it often convinces me this is how I will feel forever.

At a time and place where everything was a behaviour, and behaviour was everything, I am not quite sure how many of my parents’ friendships I detonated. To my older brother, I was the spoiled child who demanded the things I wanted and was often given them above him because it meant keeping the peace. Things like the chicken breast instead of the leg, the mini box of Fruit Loops from the variety pack at Christmas and, in my teenage years, most of the parental attention, because I was not handling things well and he seemed to be doing just fine. My younger brother was my playmate, my dress-up doll and my favourite little person, but I observed from social situations that it was more acceptable to torment younger siblings, and so that was what I began to do. I can still picture his face breaking when I made fun of his appearance right at a time when those things matter most, and I feel as crushed by it now as I did all those years ago. I dropped real friendships in favour of the ones I thought I needed to have, and took far too many years to figure out this is a very good way to find yourself all alone.

Most relationships have, at one stage or another, been similarly fraught. Well, similar in that they have been fraught – the manifestations of which have been wholly original, I will give them that. But the point is, the feedback I received on a loop from childhood through to becoming a young adult was that, nope, that is not how it is done. You are doing it wrong. This propelled me to study love – in other people, in movies and books and on television. I committed to it in an intense way I can see now is typical of my not-typical brain. I absorbed the lines and the gestures, the tropes and the endings. I repeated the words, again and again. An interesting approach, you might think, to something we are supposed to feel more than learn. But it is learned, as those of us who struggle to get it right realise. I can see with hindsight how I have tripped up, how I have failed to follow ‘the rules’ and said and done some incomprehensible things. In a lot of ways, I was doing love wrong. This was because I was intent on acting like a neurotypical person, and in order to do that I needed to smother, bury, deny and hide my autistic tendencies and needs.

And the thing is, I never passed as ‘normal’ for long; not really. “Sometimes the sound of electricity keeps me up at night,” is certainly a bold choice of conversation starter. It goes down about as well as trying to explain why I am pulling out of a commitment at the last minute because I have already allocated my social energy for the day. Or why I get so mad if I am in a car where two different conversations are happening around me at once. I cannot think of something that fills me with more rage. The one thing I will give myself credit for, though, is that I have tried. I have tried unbelievably hard. I spent years pretending I was not trying, while trying so hard and wearing myself out with both the trying and the hiding of the trying. Phew – exhausting. I put so much effort into what I thought I had to be for other people that I failed to figure out who I wanted to be for me.

My autism diagnosis gave me a context through which to understand my seemingly random struggles. The knowledge felt revolutionary. It still does.

For about 20 years, give or take, I floated so many of what I thought were my own weird little idiosyncrasies in conversations, hoping that someone else might respond with “me too” rather than a strange look and a sudden need to go and get another drink. I was starting to feel like the person in the apocalypse movie who broadcasts a radio message every day and never gets a response.

Getting an autism diagnosis in my twenties gave me the channel to tune into. It gave me people, a community at the end of my world, and it gave me hope with a new place to begin. My autism diagnosis gave me a context through which to understand my seemingly random struggles. The knowledge felt revolutionary.

It still does. I was a journalist who knew the who, where, what (me, in the drawing room, with a meltdown) and finally discovered the how and why (sensory overload, autism).

READ MORE: Five Reasons Why Being Kind Makes You Feel Good – According to Science

My diagnosis did not come from nowhere. It was the inevitable endpoint of a lot of years spent careening towards burnout and breakdown. My life was unsustainable as it was, with my career workload, unfathomably busy weekends, and never a minute to stop, to rest, to process. And it was all cumulative, every week harder than the one before. I was Artax sinking slowly into the swamp. Without any real understanding of my own support needs, I dulled sensory input with alcohol, I pushed down my emotions as a way to try and avoid dealing with them, and I was not really present in the relationships that meant the most to me. Burnout was the moment when all of that stopped working – not that it had ever really worked. I could no longer work, sleep, socialise, or function as I did before. Diagnosis was the starting point for undoing some of that damage.

Before I had the label ‘autistic’, there were many others I wore. Some given to me by other people, under their breath or to my face, and some I bestowed on myself through the worst kind of worth-eroding self-talk. Labels like sensitive, difficult, particular, snobby, rude, blunt, angry, emotional, dramatic, crazy and bad. I like autistic a lot more.

There are no right or wrong brains, all forms of neurological development are equally valid, and equally valuable. All people are entitled to full and equal human rights, and to be treated with dignity and respect.

Autistic research psychologist Jac den Houting talks about the paradigm shift around autism and neurodiversity from the medical assumption that there is one ‘right’ way to be, and any other way of being is wrong and needs to be fixed, to the view of neurodiversity as part of the range of natural variation in human neurology. They say in their 2019 TED Talk, “Just like biodiversity helps to sustain a healthy physical environment, neurodiversity can help to create a healthy and sustainable cognitive environment. There are no right or wrong brains, all forms of neurological development are equally valid, and equally valuable. All people are entitled to full and equal human rights, and to be treated with dignity and respect.”

To understand this, I needed to reframe my thinking. Reading, listening to, connecting with and talking to other autistic people about their lives and their experience of love has changed my life. Because love does not have to look like a well-behaved child, a large friendship group maintained since school, public displays of affection or the parent who turns up to all the after-school events. It can look like that, sure, but that is not the only way. What one person deems the ‘right’ way to love is ultimately subjective, and there are neuronormative expectations at every turn. Why are eye contact and “I love you” considered the markers of love in Western culture? Why not look at all the other ways an autistic person might show their love, such as being comfortable enough to be their full selves, turning to you when they are struggling, sharing their interests and wanting to be near you? Other people’s versions of showing love have not always felt like love to me. Forced hugs and “You’re fine,” and talking about that person we both like in a way that makes me wonder how you talk about me when I leave the room. I see how the word ‘autism’ is used to strip the humanity of others, how a person becomes a walking autism, to be kept over there and treated with caution or scorn. I do not like it. I want to change it. This is my attempt to change it.

“You are not like my autistic child,” is something autistic adults might hear if they start to talk about their experiences, particularly in online spaces. For some, the rise of autistic voices advocating for themselves feels like a threat to a conversation they have become used to dominating. (I am looking at you, Senator Hollie Hughes.) It seems like a no-brainer – I do not find it strange that an adult does not show many similarities to a small child, and I do not know of many non-autistic adults who resemble non-autistic children. Through this book, you will see autistic children become autistic adults, and how different they are now from their childhood selves. People who say that one autistic person is not representative of another because of the many different ways autism can present are both right and wrong – but, more importantly, they are missing the point.

To access support, of course there needs to be differentiation, although I do not believe any autistic person is at risk of being over-supported in our society. But to truly understand autism is something else entirely. It is not about how these traits look from the outside; it is not even about there being ‘traits’ or ‘presentations’ at all. A neurotype is not defined by how it looks to or impacts on other people. It is about how we feel and how we function from the inside. I cannot see the world any other way, but when I look at an emotionally dysregulated child with daily one-on-one support, or a teenager struggling socially with the high school hierarchy, or a burnt-out adult who is just finding themselves after diagnosis, I see them all as points on the same plane. I see the shared experiences and feelings, not the differences in the ways these look to other people.

A neurotype is not defined by how it looks to or impacts on other people. It is about how we feel and how we function from the inside.

Of course autism is not going to present in the same ways for everyone. People have different backgrounds, cultures, upbringings, personalities and experiences. People are at different stages of their lives. Some people need more support than others; some need lifelong support and have other coexisting conditions. But we share a way of being, a way of processing, that unites us in more ways than it separates us. And anyway, people who see autism as a list of symptoms are missing out on the best part – knowing an autistic person.

Autistic people are often criticised (I could end the sentence there) for being selfish, or self-obsessed, or tuning out other people. I worried when writing this that sharing snippets of my own story would be read as taking the spotlight away from the stories included in these pages. But I have come to understand that both the form and content of this book are autistic in nature. It is natural for me to think, and write, in tangential, associative ways. When people share their stories – gift me with their vulnerability and their open hearts – my brain rushes to bring forward the experiences of my own that match in theme or emotion. What other people often hear is “Now let me make this about me”, but what I mean is “You are not alone.” Because you really aren’t. I promise.