“Compromised and in Decline”: A Tragic Tipping Point for Our Reef

- Words by Peppermint

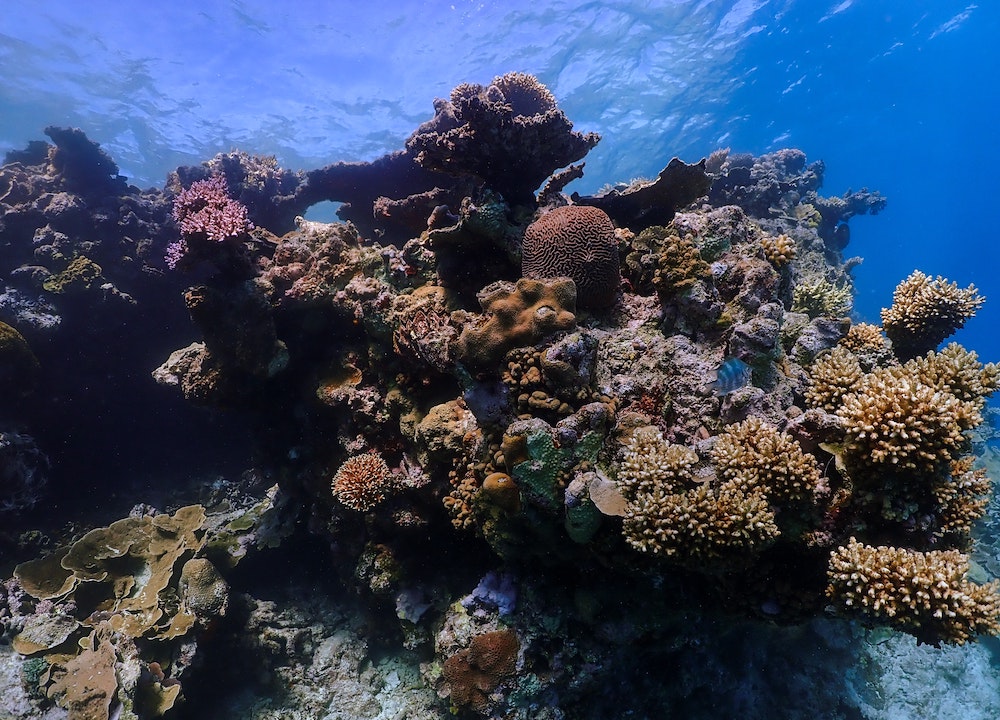

The world’s largest coral reef system, the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), has officially lost 50% of its total coral coverage, new research reveals.

The groundbreaking study, conducted by researchers from the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence’s Coral Reef Studies unit, draws on two decades’ worth of data collected between 1995 and 2017.

Findings published earlier this month in the Proceedings of the Royal Society confirm what many scientists have long feared: corals on the GBR are dying at an alarming rate.

Populations of small, medium and large corals were all found to have decreased along the length of the 340,000 square-kilometre reef, with an average depletion rate of 50%. The authors added that in some areas, all the corals had been wiped out.

We used to think the Great Barrier Reef is protected by its sheer size – but our results show that even the world’s largest and relatively well-protected reef system is increasingly compromised and in decline.

The study links declining populations with coral bleaching, which has in turn been tied to rising water temperatures and global warming. Perhaps most disturbing of all, the study purports that the GBR’s ability to regenerate after a shock event such as a mass coral bleaching has been compromised.

Up until now, many scientists subscribed to the ‘strength in numbers’ principle. Now we know this might not be the case. “We used to think the Great Barrier Reef is protected by its sheer size – but our results show that even the world’s largest and relatively well-protected reef system is increasingly compromised and in decline,” Professor Terry Hughes, former director of the centre and co-author of the report, said.

What it means for our reef…

Unfortunately, the news gets worse. As if an overall loss of coral coverage wasn’t bad enough, the study showed marked declines in large breeding adult corals as well. Fewer adults means fewer coral larvae, which will impact population trajectories for decades to come.

Of the many thousands of organisms that make up a reef’s ecosystem, corals play a critical role. They’re fundamental to biodiversity, and their loss has a cascading effect, the impacts of which we’re only just beginning to see.

The report’s authors compare corals to old-growth trees in a forest: they are the foundation on which countless other organisms, from the tiniest algae to the largest mammals, depend.

Their data shows that none of the 400-odd species of corals found on the GBR are immune from coral bleaching, but that branched and flat-topped corals are particularly vulnerable. These are the same corals that form the overall structure of the reef.

As they thin out, the ‘bones’ of the marine habitat that 1,500 species of fish depend on get smaller and smaller, as if trees in a rainforest were being logged.

PHOTO BY KRISTIN HOEL VIA UNSPLASH.

The root of the problem

What’s causing so many corals to die? During the course of the longitudinal study, several documented “reef disturbances” occurred, including a few localised cyclones and two outbreaks of deadly crown-of-thorns starfish.

But researchers point to coral bleaching as a major driver of coral loss. Two mass-bleaching events occurred in 2016 and 2017, just as the study was getting underway.

What is coral bleaching?

We’ve all seen images of pale, anaemic corals that look as if they’ve been drained of colour and life. This is coral bleaching in action, a process that causes corals to lose their vibrant colours by forcing algae from their tissues.

Coral bleaching occurs when the coral is put under stress. There are many triggers for this phenomenon, including a sudden change in ocean temperature (either an increase or a drop), overexposure to sunlight, and low tides. Coral bleaching has also been connected to water pollution from chemical runoff.

Human-induced climate change has been linked to more frequent and more intense marine heatwaves like the worst bleaching event in recorded history, which hit the GBR in 2016.

When a coral is stripped of its algae – its main food source – it is more susceptible to disease. Infectious disease outbreaks are more likely to occur in warmer waters, too. Corals can recover after a bleaching, but it often takes decades. If the bleaching is prolonged, the coral is likely to die.

This new research shows that corals on the GBR probably aren’t as resilient as scientists previously thought. Of those impacted by the bleaching events of 2016 and 2017, a large number simply died from stress.

Ocean acidification, another phenomenon that’s been linked to human-induced climate change, plays a role in reef stunting. When CO2 from the atmosphere is absorbed into the ocean, it reduces coral calcification, impacting growth rates.

It’s difficult to compare the results of this study with coral death rates pre-1995 because researchers lack the data. But it is known that coral bleaching and ocean acidification have both amped up in recent years as our oceans have become progressively warmer.

In the first months of 2020, another bleaching event occurred, and is feared to be the most widespread yet, impacting all three major sections of the reef.

PHOTO BY SAM POWER VIA UNSPLASH.

Is this the point of no return?

Although the prognosis sounds grim, authors of this latest study have been quick to point out that the Great Barrier Reef isn’t a write off. Billions of corals are still thriving on the reef and are in need of protection. Scientists are using these latest findings to call for urgent action to stabilise ocean temperatures and give damaged corals a chance to recover.

Two years ago to the week, a monumental IPCC Report warned that we have a 12-year window to curb global warming and avoid a full-blown climate crisis. The call to action has never been more urgent: if we fail to put a dint in global emissions, scientists believe that deadly coral bleaching events could become an annual occurrence.

The fate of the GBR, and other reefs around the world, hinges on the pace of climate change over the coming years. Globally, 33% of reef-building corals are threatened according to the IUCN, and UNESCO has stated all 29 World Heritage-listed reefs, including the GBR, would cease to exist by the end of the century should the status quo prevail.

The good news

Hard data like that released by the ARC this month is exactly what’s needed to spark meaningful policy change and spur civic action to safeguard the reef.

As this latest study was being digested, Citizens of the Great Barrier Reef began the process of collecting more evidence of coral decay, dispatching a fleet of tourist boats and yachts for a 10-week census of populations. A team of snorkelers and divers, many of them citizen scientists, are currently photographing and documenting coral loss in the most critical parts of the reef.

Hard data like that released by the ARC this month is exactly what’s needed to spark meaningful policy change and spur civic action to safeguard the reef.

There are some promising signs of progress in the policy world, too. Twelve months ago, groundbreaking legislation was passed in Queensland to better regulate agricultural runoff into the rivers that feed the GBR. Now a new initiative is underway to enhance water quality, with the Sydney Morning Herald reporting on a Reef Credit Scheme in the days after the research was made public. Similar to carbon offsets, the plan would incentivise landholders to work towards improved water quality.

Pollution, of course, is just one part of the problem – we still have a long way to go before rising ocean temperatures and climate change more broadly is brought under control.

words EMILY LUSH top image MANNY MORENO via UNSPLASH

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Brighten up your inbox with our not-too-frequent emails featuring Peppermint-related news, events, competitions and more!

explore

More articles

It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas…. Which means we are officially entering party season. Work parties, friend-dos, family get-togethers and then we’re straight into New Year festivities. If you’re lucky enough, you might be staring down the barrel…

Look, I don’t want to make anyone panic but IT’S DECEMBER!!! If you’re planning to give homemade gifts, you’re going to have to act fast. …

Furred, feathered, fishy, scaled… The pets we choose are as diverse as our personalities. (And apparently, quite often we resemble each other.) But they all…

When you hang a painting on a wall, the story stays put. But when you wear a beautifully made garment that may as well be…

Hang out with us on Instagram

Any New Year’s resolutions on your list? We love this from @OtterBeeStitching - “be brave enough to suck at something new”.

There’s no points for perfection, but you’ll get a trophy for trying. If nothing else this year, take the leap and try something new.

#OtterBeeStitching #Embroidery #BeBrave #TrySomethingNew #EmbroideryArt

Sunday serving suggestion ☀️

Gorgeous photos from @JolieFemmeStore - who make sweet garments from vintage bedsheets.

#PeppermintMagazine #SlowSunday #SwitchOff #Unplug #ReadAMagazine

A toast to the old you 🥂

We wholeheartedly love this post from the brilliant @EmilyOnLife:

“2026: Reinvent, burn it down, let it go (whatever it is). Year of the Snake it up. Exercise your boundaries, exercise your body, take one teeny step every day towards a life that feels better to be in.

But don’t you dare shit on your old self while you do it.

Hold yourself with reverence and tenderness and respect, because you got you this far. You did your very best with the information and tools you had at the time. You scraped yourself together, you made it work, you survived what felt impossible to survive: again and again and again.

You are perpetually in the process of becoming, whether you can feel it or not, whether or not you add it to your 2026 to-do list.“

Some very wise words from @Damon.Gameau to take us into 2026 🙌🏼

⭐️ We made it!!! ⭐️

Happy New Year, friends. To those who smashed their goals and achieved their dreams, and to those who are crawling over the finish line hoping to never speak of this year again (and everyone else in between): we made it. However you got here is enough. Be proud.

It’s been a tough year for many of us in small business, so here’s to a better year in 2026. We’re forever grateful for all your support and are jumping for joy to still be here bringing you creativity, kindness and community.

We’re also excited to be leaping into the NY with our special release sewing pattern – the Waratah Wrap Dress!

How great are our fabulous models: @Melt.Stitches, @KatieMakesADress and @Tricky.Pockets - and also our incredible Sewing Manager @Laura_The_Maker! 🙌🏼

Ok 2026: let’s do this. 💪🏼

#PeppermintWaratahWrapDress #PeppermintPatterns #SewingPattern #MeMade #WrapDress #WrapDressPattern

Putting together our annual Stitch Up brings on all the feels! We feel humbled that you’ve chosen to sew Peppermint patterns, we feel inspired by the versions you’ve created and we feel proud of you.

Where to begin?! As always, there has been a plethora of Peppermint patterns flooding our feeds this year, and we wish we could showcase more than just a handful of magnificent makes from you, our clever community. We encourage you to flip through the me-made items in your wardrobe or scroll through your grid and remind yourself of the beauty you’ve created with your own two hands (and maybe a seam ripper and some choice words). Congratulations to all of us for our creative achievements this year!

We’ve put together some (but absolutely not all) of our favourites from 2025 over on our website. We hope it inspires your next make!

🪡 Link in bio 🪡

Pictured: @FrocksAndFrouFrou @MazzlesMakes @KatieMakesADress @_Marueli_ @IUsedToBeACurtain @Nanalevine.Couture @PiperInFullColour @MadeByMeJessieB @SarahMalkawi @Made.By.Little.Mama

#PeppermintPatterns #SewingPatterns #MeMade #MeMadeEveryday