A Letter on Gender by Queer Rights Activist Deni Todorovič

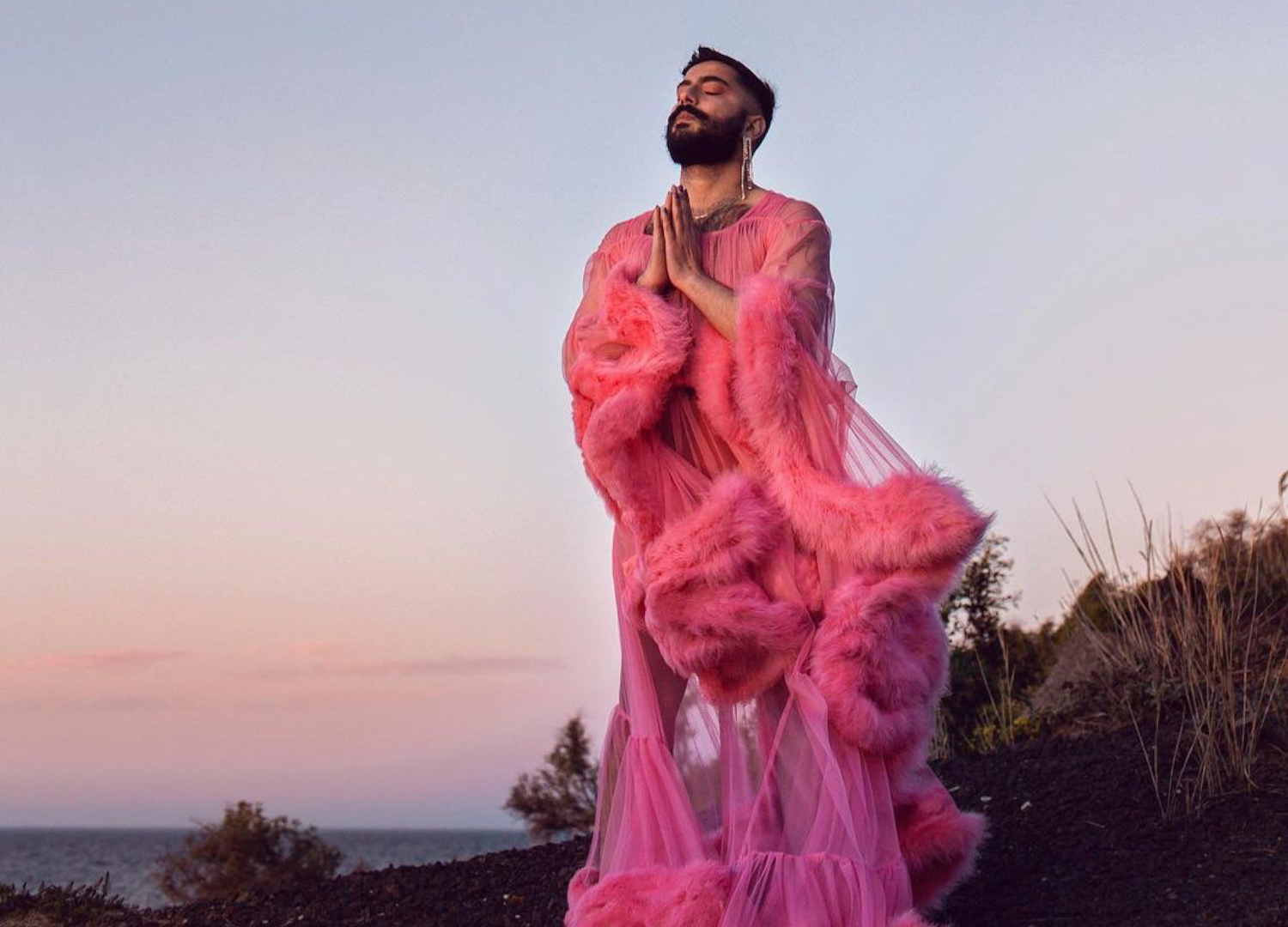

words DENI TODOROVIČ photos SUPPLIED

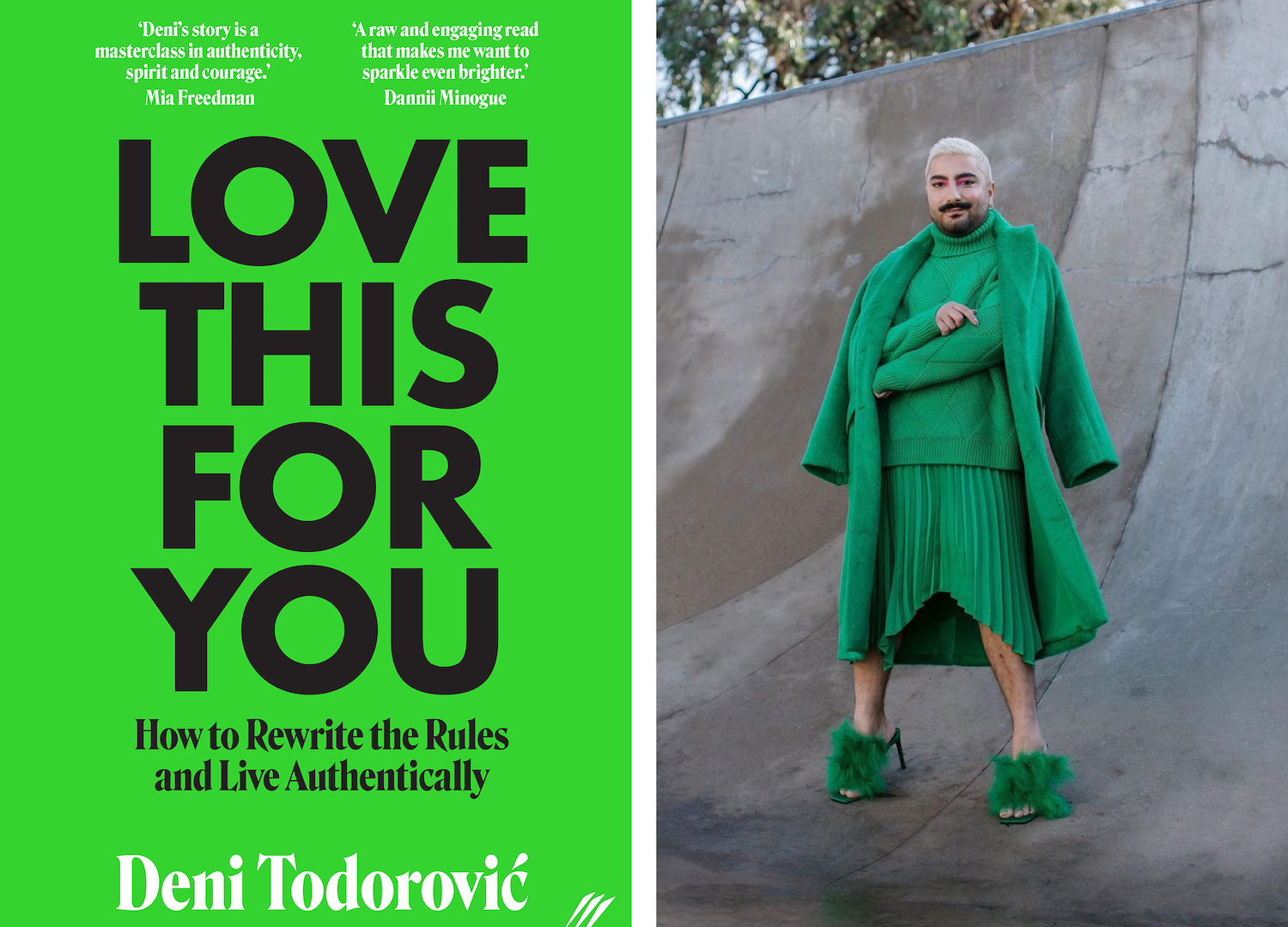

A vocal activist for queer rights, co-host of the podcast What Are You Wearing? and the human behind popular style Instagram account @StyleByDeni, Deni Todorovič is candid about their difficult journey to self-acceptance. In this powerful extract from their first book, I Love This for You – a tome about writing your own rules and living life authentically – they speak to breaking away from the binary and the power of being kind.

I receive DMs from parents almost daily asking me to write a book themed on gender, and in many ways that would have been the expectation for this book. Since coming out as non-binary two years ago, I have dedicated a whole lot of space to conversations around gender and living beyond the binary. Social media space, podcast space, written space.

The truth is, though, I am still very much on my own gender journey, and there are other humans much further down their journey with non-binary identities, with far greater expertise on the subject than me at present. Humans like Jeffrey Marsh and Alok V Menon. If you are unfamiliar with either of them, I encourage you to look them up and devour both their books and content. That being said, it would be weird if I didn’t cover the biggest sliding-door moment of my life thus far to some capacity. As I’ve mentioned, I credit the long hours of lockdown for this turning point in my life; it was that blessing of time and space that really allowed me to look inwards and really do the work. So, in an attempt to give you a breather before we jump into another very meaty chapter, I wanted to share some of my thoughts on gender with you.

The first thing to note is that sex and gender are two very separate things that often get confused as the same. When we each enter this world, we are assigned a sex at birth, traditionally declared male or female or intersex, based on the genitals between our legs. In delivery rooms the world over, obstetricians will traditionally announce one of two sentences to eagerly anticipating parents: “It’s a GIRL” or “It’s a BOY”.

An important note here: being intersex is not my lived experience, but people living with intersex variations are constantly overlooked in conversations about sex and gender, even though research tells us that 1.7% of the population are born with intersex variations, which is the same number of people born with red hair! For more information and resources on the intersex community, I highly recommend you head over to the Intersex Human Rights Australia website.

Why is there such universal pressure and expectation placed on humans who have barely opened their eyes to possess a certain gender identity?

My mum has told me that during her pregnancy when she heard I was going to be a ‘boy’, she felt waves of sadness, having hoped that she would be blessed with a daughter. I’ve heard stories of parents’ genuine anguish over the sex of their children.

But why is there such universal pressure and expectation placed on humans who have barely opened their eyes to possess a certain gender identity?

This, my darlings, is where gender comes into play and sex assigned at birth is left far behind. In my very first session with Elise [Reiki, a trauma-specialist psychotherapist, healer and holistic practitioner], she described me as someone with more feminine energy than she had seen in even some of her cisgender female clients. She said this existed in me alongside the masculine, creating a combination that went beyond the male/female divide. In many ways, it was this session that led me towards my own journey of gender discovery.

To explain it very simply, I identify as non-binary. To make that make sense, I will first explain to you what a binary system means. The word binary is used when referring to a system that consists of two things. In the case of gender identity, it has for a long time, especially in western history, been considered to consist of only male and female. But we know of many examples across First Nations and eastern cultures of gender identities that transcend these rigid binary norms. What’s more, people who live with what we understand in western terms as trans or gender-diverse identities have often been celebrated or lifted up within their communities, seen to possess invaluable insight based on their unique experiences with gender. A few examples include Brotherboys and Sistergirls from First Nations communities in Australia, to two-spirit Native Americans and the ‘third gender’ Fa‘afafine peoples of the Samoan diaspora.

Non-binary means that I, and individuals like me, can’t exist within traditional societal categories of man or woman. Within the non-binary umbrella there is a variation of identities, from gender nonconforming to genderfluid and genderqueer. Gender expression and gender identity are unique to each individual’s lived experience, and there’s a great deal of nuance to understand here. Let’s start by defining those ideas.

Gender expression refers to the ways that a person’s behaviour, mannerisms and appearance come to be associated with feminine or masculine gender roles. This is about someone’s external presentation (think clothing, hair, makeup, etc), and these categories often rely on gendered assumptions and stereotypes about how ‘men’ or ‘women’ should behave in our society.

Gender identity is more of an inward-facing concept about how we understand our own gender. When someone is cisgender, their gender identity correlates with their assigned sex; when they are trans and/or non-binary, their gender differs from their assigned sex. Our gender identity is who we know ourselves to be.

Every non-binary journey is different…

Non-binary humans also sometimes use the term trans to describe themselves, as by definition transgender means not identifying with the sex assigned to you at birth. So within the trans umbrella, you have binary transitions – think Caitlyn Jenner, a rather problematic woman most globally known for a transition many of us witnessed via her family’s television show. May I point you in the direction of the exceptional Laverne Cox instead? Thank me later.

In these binary transitions, it can be common to pursue medical intervention, such as hormones and surgery – though not always. An operation or injection does not validate or invalidate someone’s gender, but it can do a great deal in helping them to outwardly express their internal sense of self. For non-binary folks, medical interventions are less common, but as with any identity group, there are huge variations between experiences of non-binary identity. Some transitions involve medical intervention with hormones for example, but other people might not tie their non-binary identity to external changes in our bodies. Every non-binary journey is different; this all varies from person to person.

A lot to digest? I know, it was for me too.

READ MORE: Five Reasons Why Being Kind Makes You Feel Good – According to Science

You may have noticed that I introduced myself in this book with my pronouns, they/them, just as they’re displayed on my Instagram and on the Instagram bios of many humans, both cishet or not. The reason you might have noticed this ‘trend’ of late is because with an increasing awareness of the complex nature of gender identity comes a rising consciousness that we cannot judge any human by how they present themselves. So by me and others being very clear with our identity and the pronouns we use, there is no room for misgendering. That’s when you use pronouns or a form of address that doesn’t reflect a person’s gender identity.

With an increasing awareness of the complex nature of gender identity comes a rising consciousness that we cannot judge any human by how they present themselves.

Not only is misgendering harmful to the trans community – research shows a direct correlation between misgendering and poor mental health, self-harm and suicide – it can also stir up feelings of gender dysphoria in trans people, amplifying their discomfort or distress over the sense of mismatch between their gender identity and their sex. Imagine being perceived and spoken to every single day with language that doesn’t reflect the way you identify. You’d feel hurt, invisible, unappreciated and disrespected. The other great benefit of being both vocal and visible with your pronouns is that it shows allyship, and it gives space for those around you to do the same safely.

If you take one thing away from this, I would love for it to be the following: no two people share the same lived experience, but every single person in this world is, in some way, shape or form, either benefiting from or carrying baggage based on their gender.

Get to know the nuanced, intersectional nature of feminism. Become familiar with the fact that feminism must include all women, including trans women, because trans women are women. Know that the journey of a white woman will never be the same as that of an Indigenous or Black woman, or women of colour. We must understand that a trans person doesn’t have the same social privilege as a cis person.

No two people share the same lived experience, but every single person in this world is, in some way, shape or form, either benefiting from or carrying baggage based on their gender.

Never underestimate the impact that even your micro-expressions of allyship can have on queer people. Put your pronouns in your bios and email signatures. Use them in team meetings. Wear those rainbow lanyards with pride, pin those pronoun badges to your uniform. Smile at that trans person opposite you in the line at Starbucks. It all goes such a long way and means more to us than you may ever know.

So please, be kind. Lead with empathy and respect, and a knowledge that while you may never understand the lived experience of another, you can still very much stand alongside them with your support and allyship. No matter the pronouns we use.

Extract from Love This for You (Pantera Press) by Deni Todorović, RRP $32.99, on sale now!