Strength, Resilience and Success: The Game-Changing Rise of Women’s Sport

- Words by Peppermint

words CHLOE DALTON above VIA INSTAGRAM

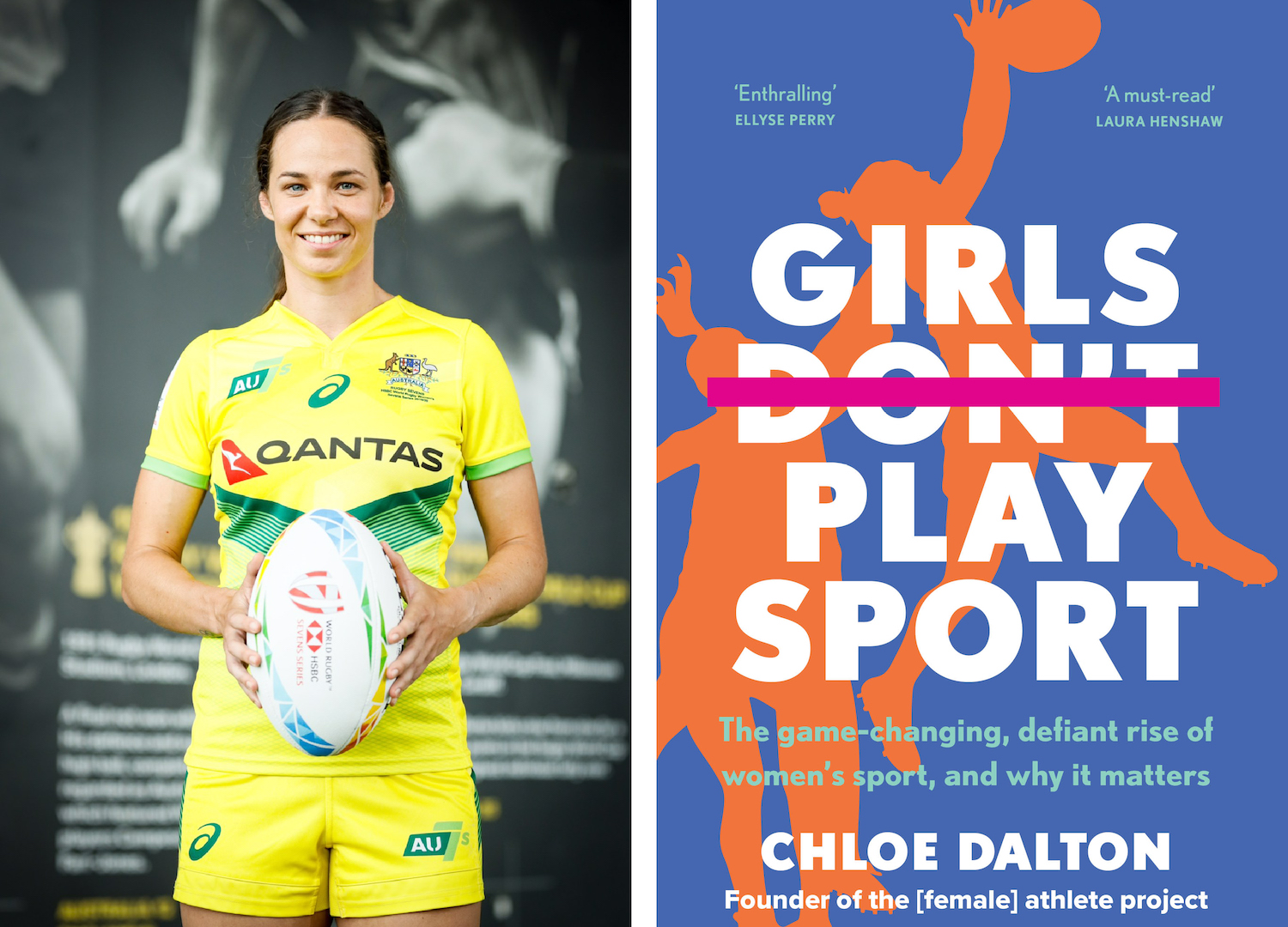

While Tillies fever rightly catapulted the Women’s World Cup into living rooms and front pages across the country, athletes have long been fighting for an equal playing field. In her debut book, Girls Don’t Play Sport, Chloe Dalton – a professional AFL and rugby union player who won gold with the rugby sevens at the 2016 Olympics, and the founder of The [Female] Athlete Project – explores the game-changing, defiant rise of women’s sport, and why it matters.

As a young kid, I would sit on the hill at my local rugby club and watch my brothers play. At half-time, I would take a cone out, put the ball on it, and try to kick it from the sideline. I wasn’t too bad at all. Grown men would come up to me and say, “You should play rugby.” I would turn to them, a confused look on my face, and say, “Girls don’t play rugby.”

Sixteen years later, at the 2016 Rio Olympics, I stood on top of the Olympic podium, arm in arm with my teammates, an Olympic Gold Medal around my neck, after defeating New Zealand 24–17 in the rugby sevens’ Games debut.

Many of my own teammates were forced to stop playing the game they loved at 12, because at that age they were no longer allowed to play with the boys.

But throughout my childhood, I couldn’t see female sporting idols on television or in the newspaper, or hear about them on the radio. For decades, women have been underrepresented across all facets of sport, from playing to coaching to administration and management. Many of my own teammates were forced to stop playing the game they loved at 12, because at that age they were no longer allowed to play with the boys. As grown women, they returned to the game to wear uniforms designed for men, use change rooms without appropriate amenities and train on the backfield with inadequate lighting.

above VIA INSTAGRAM

Some men’s sports, clubs and teams have existed for over a century. I recently saw a post by the Carlton Football Club celebrating three generations of footballers from the same family. One of Carlton’s young players, Jack Silvagni, had become the third footballer in his family to play 100 games for the club, as both his father and grandfather had done before him. As a former Carlton player myself, I couldn’t help but feel so happy for Jack, who gives his all every time he steps out onto the ground. But the second thing that came to mind was that it will be years before the first AFLW player even hits 100 games, let alone her daughter and her daughter’s daughter. Women’s sport is often entire generations behind the men’s game, and yet they are constantly compared in terms of score lines, skill execution, entertainment factor and crowd numbers. It’s like comparing the revenue and success of McDonald’s (which opened in the 1950s) with that of a small, Australian-owned burger business in its infancy. They are completely different propositions.

For decades, men’s sport has been the default. Often, when a new women’s competition is introduced, a ‘W’ is simply added to the default name of the league or club. Think of Australian rules football: we have the AFL, and then we have the AFLW. When Australia’s men’s domestic basketball league was formed in 1979, it was named the National Basketball League. When the Women’s Interstate Basketball Conference became a nation-wide league in 1982, however, it was named the Women’s National Basketball League. Yet the men’s competition has never rebranded to include the word ‘men’s’.

For female athletes, language can be a harmful tool that reminds them that they are not part of the fabric of sport – that their contribution is added in, second string.

To many, I am known as a female athlete who plays women’s sport. Have you ever heard Tiger Woods referred to as a male athlete who plays men’s golf? That sentence sounds ridiculous because it is never used. Yet for female athletes, language can be a harmful tool that reminds them that they are not part of the fabric of sport – that their contribution is added in, second string.

In research conducted by Mikaela Wapman and Deborah Belle through Boston University, 197 psychology students and 103 children aged seven to seventeen were given a riddle: “A father and son are in a horrible car crash that kills the dad. The son is rushed to the hospital. But just as he’s about to go under the knife, the surgeon says, ‘I can’t operate—that boy is my son!’ Explain.”

Only 15% of the children and 14% of the psychology students came up with the answer that the mother of the child was the surgeon.

READ MORE: How Owning Your Power Can Help Build a Better System From the Inside Out

The idea for the research came about when Belle asked her 10-year-old granddaughter to solve the riddle, and found she could not. Her granddaughter said, “How could this be? Well, he could have two fathers.” While that scenario was absolutely a possibility, the fact that the mother didn’t emerge as an option prompted the researchers to look into the gender ‘schemas’ – or generalisations – that help us to explain the complexities of the world. Interestingly, these gender schemas don’t necessarily reflect our personal values or the experiences we, as individuals, have had. This means that even a student whose mother is a doctor won’t necessarily propose that the surgeon in the riddle might be the boy’s mum.

Virginia Valian, a Hunter College psychologist, has noted how people who are presented with a man and a woman with the same CV typically assume the man is more competent. Her work argues that we absorb gender schemas at a very young age. Belle, discussing Valian’s ideas, says that “when it comes to gender, we fixate on women’s reproductive functioning, and we sort of allot competence to men. Experience can have some effect in our schemas, but much less than we might anticipate.” Virginia has also observed that men and women have identical schemas when it comes to gender – which is exactly what the Boston University research found.

I’ve been part of many teams over the last two decades, and in each one there has been a strong sense of belonging and camaraderie amongst my team mates. The sense of greater purpose and community within these teams makes me feel so grateful that I’m able to play sport for a living. But beyond these tight-knit inner circles, women at all levels of sport are often told that they don’t belong. Not necessarily out loud, but in a range of indirect ways. Whether they’re being placed out on the back field with poor lighting, or being part of a club that doesn’t have female change rooms, or being given hand-me-down uniforms from the men’s team, with the excuse that the club doesn’t have enough money to cover specific uniforms for women, women constantly fight against long-held attitudes and stereotypes: “No-one wants to watch women’s sport,” “They’re nowhere near as good as the men,” “You don’t deserve equal pay.”

Disrespectful attitudes about women in sport perpetuate harmful attitudes about women in society. But I believe sport has the power to change people’s attitudes about women as a whole – our strength, our resilience and our success.

Because of these stereotypes, and a number of other factors, few elite sportswomen have crossed the line to become completely professional. Many female athletes work full-time jobs as well as play, and are glorified for the way they balance multiple roles all at once – athlete, employee, role model and sometimes mother.

On social media, female athletes are often targeted for their ability, performance or image. I read comments daily on posts about women’s sport like, “Get back in the kitchen and make me a sandwich.” Disrespectful attitudes about women in sport perpetuate harmful attitudes about women in society. But I believe sport has the power to change people’s attitudes about women as a whole – our strength, our resilience and our success. Many women have pioneered the way for the next generation of young people coming through today. At the T20 Women’s Cricket World Cup in 2020, 86,000 people watched Australia defeat India at the MCG. Over four million people tuned in to watch icon Ash Barty win the Australian Open in 2022, the most watched women’s singles final since records began in 1999. According to ESPN, in 2022, six of the top 10 “most marketable” college basketball players in the USA were women. In 2022, the AFLW saw more than one million people pass through the gates. This top-tier success has translated at a grassroots level, too: between 2016 and 2021, the number of women’s and girls’ football teams in Australia has grown from 983 to more than 2500.

The game has changed. It’s time for women in sport to receive equal opportunity, pay, representation and respect.

This is an extract from Girls Don’t Play Sport – The Game-Changing, Defiant Rise of Women’s Sport and Why It Matters by Chloe Dalton (Allen & Unwin, August 2023).

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Brighten up your inbox with our not-too-frequent emails featuring Peppermint-related news, events, competitions and more!

explore

More articles

Look, I don’t want to make anyone panic but IT’S DECEMBER!!! If you’re planning to give homemade gifts, you’re going to have to act fast. …

Hang out with us on Instagram

🌻 The Paddington 🌻

This is a much-loved staple, created for Issue 50 in 2021. We love seeing the #PeppermintPaddingtonTop continually popping up in our feeds!

How stunning is our model Elon MelaninGoddessEfon – she told us it was one of the first times she had been asked to come to a shoot with her natural hair. 🌻

We worked with South African patternmaker Sarah Steenkamp of @FrenchNavyNow_ to create this wardrobe essential – the perfect puff-sleeve blouse. Raglan sleeves make it the ultimate beginner sew, plus the gorgeous back buttons let you add your own personal twist.

Pattern via the link in bio! 🪡

Photos: @KelleySheenan

Fabric: @Spoonflower

Model: MelaninGoddessEfon

“In the 1940’s, Norwegians made and wore red pointed hats with a tassel as a form of visual protest against Nazi occupation of their country. Within two years, the Nazis made these protest hats illegal and punishable by law to wear, make, or distribute. As purveyors of traditional craft, we felt it appropriate to revisit this design.”

Crafters have often been at the heart of many protest movements, often serving as a powerful means of political expression. @NeedleAndSkein, a yarn store in Minnesota, are helping to mobilise the craftivists of the world with a ‘Melt The Ice’ knitting pattern created by @Yarn_Cult (with a crochet pattern too), as a way of peaceful protest.

The proceeds from the $5 pattern will go to local immigrant aid organisations – or you can donate without buying the pattern.

Raise those needles, folks – art and craft can change the world. 🧶

Link in bio for the pattern.

Images: @Gather_Fiber @NeedleAndSkein @a2ina2 @KyraGiggles Sandi.204 @WhatTracyMakes AllieKnitsAway Auntabwi2

#MeltTheIce #Craftivism #Knitting #CraftForChange

TWO WEEKS TO GO! 🤩

"The most important shift is moving from volume-led buying to value-led curation – choosing fewer, better products with strong ethics, considered production and meaningful stories. Retailers have real influence here: what you buy signals what you stand for. At Life Instyle, this means using the event to discover and invest in small-scale, planet-considerate brands that align with your values and your customer’s conscience. Consumers don’t need more things; they need better things, and retailers play a key role in selecting, contextualising, and championing why those products matter."

Only two more weeks until @Life_Instyle – Australia`s leading boutique retail trade show. If you own a store, don`t miss this event! Connect with designers, source exquisite – and mindful – products, and see firsthand why this is Australia’s go-to trade show for creatives and retailers alike. And it`s free! ✨️

Life Instyle – Sydney/Eora Country

14-17 February 2026

ICC, Darling Harbour

Photos: @Samsette

#LifeInstyle #SustainableShopping #SustainableShop #RetailTradeEvent

Calling all sewists! 📞

Have you made the Peppermint Waratah Wrap Dress yet? Call *1800 I NEED THIS NOW to get making!

This gorgeous green number was modelled (and made) by the fabulous Lisa of @Tricky.Pockets 🙌🏼

If you need a nudge, @ePrintOnline are offering Peppermint sewists a huge 🌟 30% off ALL A0 printing 🌟 when you purchase the Special Release Waratah Wrap Dress pattern – how generous is that?!

Head to the link in bio now 📞

*Not a real number in case that wasn`t clear 😂

#PeppermintWaratahWrapDress #PeppermintPatterns #SewingPattern #WrapDress #WrapDressPattern

8 Things to Know About January 26 - from @ClothingTheGaps:

Before you celebrate, take the time to learn the truth. January 26 is not a day of unity it’s a Day of Mourning and Survival for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It marks the beginning of invasion, dispossession, and ongoing colonial violence. It’s time for truth-telling, not whitewashed history.

Stand in solidarity. Learn. Reflect. Act.

✊🏽 Blog written by Yorta Yorta woman Taneshia Atkinson.

🔗 Link in bio of @ClothingTheGaps to read the full blog

#ChangeTheDate #InvasionDay #SurvivalDay #AlwaysWasAlwaysWillBe #ClothingTheGaps

As the world careens towards AI seeping into our feeds, finds and even friend-zones, it`s becoming increasingly hard to ignore.

We just wanted to say that here at Peppermint, we are choosing to not print or publish AI-generated art, photos, words, videos or content.

Merriam-Webster’s human editors chose `slop` as the 2025 Word of the Year – they define it as “digital content of low quality that is produced usually in quantity by means of artificial intelligence.” The problem is, as AI increases in quality, it`s becoming more and more difficult to ascertain what`s real and what`s not.

Let`s be clear here, AI absolutely has its place in science, in climate modelling, in medical breakthroughs, in many places... but not in replacing the work of artists, writers and creatives.

Can we guarantee that everything we publish is AI-free? Honestly, not really. We know we are not using it to create content, but we are also relying on the artists, makers and contributors we work with, as well as our advertisers, to supply imagery, artwork or words created by humans. AI features are also creeping into programs and apps too, making it difficult to navigate. But we will do our best to avoid it and make a stand for the artists and creatives who have had their work stolen and used to train AI machines, and those who are now losing work as they are replaced by this energy-sapping, environment-destroying magic wand.

Could using it help our productivity and bottom line? Sure. And as a small business in a difficult landscape, that`s a hard one to turn down. We know other publishers who use AI to write stories, create recipes, produce photo shoots... but this one is important to us.

`Touch grass` was also a Merriam-Webster Word of the Year. We`ll happily stick with that as a theme, thanks very much. 🌿