When Peppermint Met Safia

- Words by Peppermint

It’s Fashion Revolution Week – the week where everyone has the question ‘who made my clothes’ on their lips and in their Instagram feeds. But long before this movement began, Safia Minney was the woman asking this question and spearheading many ethical and sustainable initiatives, from World Fair Trade Day in 1999 to the pioneering label People Tree in 2000. Now an expert in the field of supply chains and sustainable fashion, with many years of experience, accolades, awards, books and documentary appearances under her (ethical) belt, Safia’s turning her tireless efforts towards her role as Managing Director with Po-Zu – ‘shoes with a good sole’. Our Editor-in-chief Kelley was in London recently and caught up with Safia to chat about Po-Zu, microfibres and how the ethical fashion movement is faring in the UK.

Tell me when and why you started working with Po-Zu?

I started at Po-Zu in January 2017. Sven Segal [Po-Zu’s founder] is fabulous, because having founded People Tree, it’s great to work with a kind of male version of myself; someone who’s really committed to changing the fashion industry but in a very grassroots way – as a designer using sustainable materials and environmentally-friendly production methods and dedicated to getting a really strong product out there in the market, but also campaigning for change.

How long has Po-Zu been around for?

Po-Zu’s been going for over 11 years now. It was a very, very small niche brand, and joining Sven and the team has been really an opportunity for the business to mainstream ethical footwear.

That came about I think with a couple of things. Firstly that we were having more and more people coming to us asking for collaborations, so after the Timberland collaboration, we did the collaboration with Star Wars. And that helped us to get a whole new audience of people considering sustainable footwear and ethical fashion.

ABOVE RIGHT: SAFIA MINNEY WITH SVEN SEGAL

Were ethics and sustainability at the core of what Po-Zu was about from the beginning or did it evolve along the way?

Sven started the brand because he was really shocked at the conditions in which shoe workers were working in – there are highly toxic chemical solvents that they were inhaling in the factories. And he wanted to put a brand into the market that was the best possible practice, both in terms of how it treated the workers and the materials that were being used. There are also repair functions so that the shoes can be repaired easily.

And I think the new initiative, the new ethical Sri Lankan supply chain that I’ve set up, will have a product that’s the same price as most mainstream sneaker brands, but made using organic cotton and fair trade rubber. So I think it’s really this question of how can you bring ethical and sustainable footwear to a much, much bigger audience at an affordable price?

Tell me about the shoes themselves – what makes them ethical and sustainable?

Lots of things really! The materials – we try to not ever use any kind of synthetic. But having said that, there’s also a growing market for vegan shoes, and we’ve resisted the temptation of making shoes in plastics that are completely unbiodegradable.

So we tend to use organic cotton for the uppers, and also Pinatex which is a pineapple leaf fiber, which is a great alternative to leather for summer shoes. And we’ve been using heritage tweeds which look beautiful – it’s very much the signature of the brand – and with it things like cork, which is a beautiful sustainable material which is also local to Portugal, which is where we make a large part of the premium collection.

You mentioned about the shoes being repairable, which is an important element of sustainability. Can they be repaired by the consumer or do they need to be sent back to Po-Zu?

Alot of people are choosing to repair them themselves, because the Portuguese products are hand-stitched, which means that it can be really easily hand-stitched. And Po-Zu will also repair shoes.

The dream is that we’ll have an ability to have a repair function as part of a shop, and as we grow the business, to have shops where you can buy shoes and also get them repaired. Unfortunately, if you’re based in Australia, that’s a little more difficult for now!

Sustainable fashion is something that consumers are becoming more aware of, but shoes are often the last on the list. Do you feel that that’s the case?

Yes – certainly sustainable clothing has had a good 15 years to really grow as a market sector, there are lots of brands now. I think there are beginning to be more and more ethical shoe brands. And I think that’s a really healthy thing, it gives consumers more options. Certainly when I was running People Tree, I would be creative directing the shoots and finding it was incredibly difficult to find ethical and sustainable footwear that really looked right. And I just didn’t want to use vegan plastic shoes.

A lot of the ethical footwear brands that are vegan are plastic shoes. Having lived in Japan for 20 years, which gets very hot in the summer, I didn’t want to have constant sweaty feet from wearing plastic shoes, and then the sense that this pair of shoes is around for literally 100 years or so.

So I think it’s important to find and develop those alternatives, and that’s been very exciting at Po-Zu to bring my fair trade supply chain development skills to footwear in this case, and to a great brand that’s really very much advocating for change in the fashion industry. But you’re right, shoes are way behind clothing, aren’t they?

By adding the repair element to the shoes, it helps to contribute to the closed loop concept. Why is the circular economy important?

I think we’re all consuming way too much in the way of clothing and shoes. And if we can take clothes and shoes and reuse and repair, it’s going to reduce the demand. Even though obviously it’s great, it’s also incremental – it requires for huge portions of the population to really rethink the way they consume and wear clothing and shoes.

We have a number of different initiatives now where you can rent clothing. And I think that’s really exciting. If you need a gorgeous occasion dress you might not want to buy one, you can go and rent one for a subscription fee every month to be able to wear something that you possibly couldn’t afford if you were buying it – a beautiful designer piece dress that might cost anything up to £900 pounds that you could wear once and really enjoy wearing for a very small rental fee.

I think that those kinds of initiatives are really, really exciting. And they kind of create more options around the swapping clothes events that we’ve had here, and the charity and vintage shop events that have been very, very popular – people are attending make and mend workshops and learning a bit more about how to upcycle and how to repair their clothes. It’s always surprising to me that people don’t know how to sew a button on, or sew a button shank. But these are things that are quite basic skills that really help us to reduce our consumption of new clothes.

I think we’re all consuming way too much in the way of clothing and shoes. And if we can take clothes and shoes and reuse and repair, it’s going to reduce the demand.

Do you feel the general public in the UK are aware of ethical fashion and what they can do? Or do you think it’s still quite niche?

I think awareness levels have grown phenomenally in the last five years. But it is still very niche. We talk about one in three people are cultural creatives, they have the power as consumers and as citizens and professionals in companies, workers in companies, to really change their family, their community, and their workplaces.

But I think there’s still a shyness about standing up against what seems like the status quo, the norm, and it’s making that okay. Certainly when The True Cost movie was out, a lot of fashion companies, fashion buyers, fashion merchandisers and designers showed the film in their workplace as well as in community groups and clubs and student bars. And I think that has made it a little bit easier to talk about sustainability and better practice. But it’s unfortunately still very far away from the norm.

I’ve heard you talk about microfibres – why is that such a problem for so many areas, including the food chain and the oceans?

Certainly for brand owners like myself, for People Tree, when we were very, very committedly trying to develop better prices and wages and community development for farmers so that they could switch from conventional cotton to organic cotton, we found ourselves up against a huge audience of people that would say, “Oh yeah, but it’s better to make the synthetics, cotton uses a lot of water,” which completely ignored the fact that you can drip irrigate if you need to.

And often organic cotton is rain fed, and what you’re doing is you’re keeping nutrition, and you’re keeping live matter in the soil. The soils are fertile, they’re bouncy, they’re sponge-like, so keeping the strength of soil fertility and a healthy ecosystem where it’s needed so that farmers can benefit from growing other crops alongside and often in-between the organic cotton. I’ve seen aubergine, tomatoes, and all kinds of vegetables actually grown in-between the organic cotton plants.

But I think what has been shocking is this complete denial that synthetics actually not only are very expensive to produce and are based on oil economies, but that they are completely unbiodegradable, hanging around as one to five millimeter fibers in the environment and our tap water. More than 80 percent of our tap water is now contaminated, and then in the oceans microfibers are being ingested by fish and then turning up in our food chains and food systems. This was something that we all thought was happening, but only relatively recently has there been proof of that, and it has become a public campaign to really look at plastic use and plastics that can be in fashion chains, in fashion products, and how they can be avoided.

So I think, certainly for me personally, it’s this question of social justice and environmental justice coming together, and that we ask citizens – do you really have the choice of buying non-plastic and creating livelihoods for cotton farmers?

We are talking after all about a cotton economy in many African countries being more than 60 percent of GDP, and we’ve got huge cotton growing subsidies that are being paid to American farmers of more than three billion pounds a year, which meansthat it’s bringing down the international cost price of cotton by about 25 percent. This is an international trading system that’s really keeping the poor even poorer, and then the alternative of a synthetic fiber is polluting our oceans and our human health and marine health. I find it completely unjust.

What are your thoughts on recycled plastic textiles?

15 years ago I think recycled bottle initiatives were beginning to appear, and we all thought that it would somehow be useful. But clearly the number of bottles that we’re generating are way too many to be recycled into fabric that then bleeds a quarter of a million microfibers every wash into water.

So it isn’t a solution, we shouldn’t be creating plastics in the first place in the quantities that we are. I think it’s quite possible to cut plastic production by nine tenths and still manage the transition.

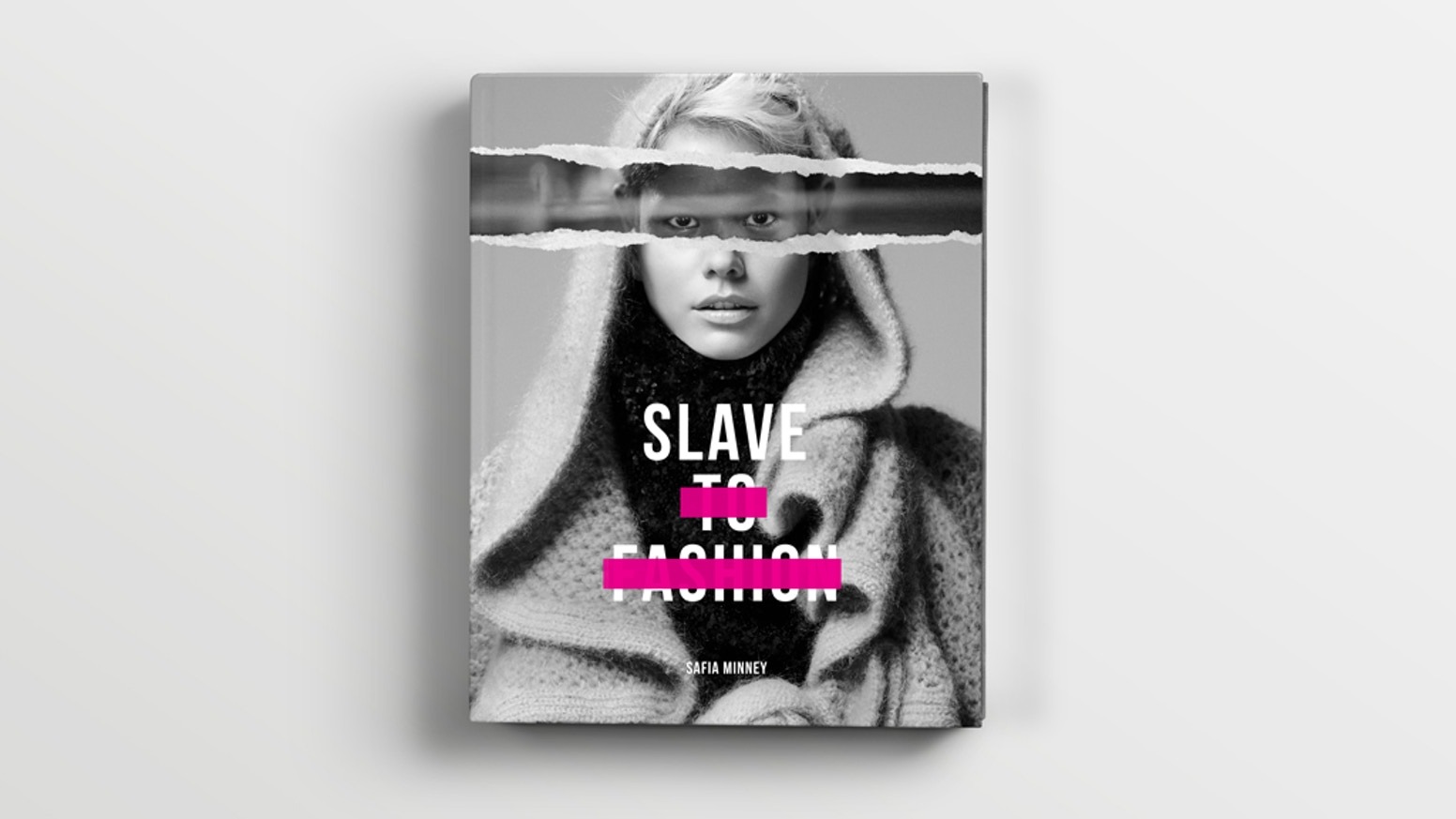

SAFIA MINNEY’S BOOK ‘SLAVE TO FASHION’ CALLS ATTENTION TO MODERN-DAY SLAVERY IN THE GARMENT INDUSTRY.

In the UK, can consumers easily find ethical brands on the high street or in department stores where the majority still shop? In Australia, David Jones is committed to ethical sourcing and many major labels have well-known certifications, like Ethical Clothing Australia. Is there anything similar in the UK mainstream?

You can find some of the larger brands – for example People Tree is available in John Lewis and Westfield, which is one of the biggest shopping areas in London. There are obviously dedicated ethical fashion boutiques that stock People Tree too, like The Keep in Brixton.

But to be honest, it’s disappointing. Ethical fashion should be way more accessible, you should be able to walk out of your door and into a market town and find it relatively easily. But unfortunately it’s still quite difficult to find.

But this is all about consumer power, isn’t it? We’ve got to create alternatives in the same way that people struggled to get fair trade coffee onto the supermarket shelves. We’ve got to do the same by demanding that sustainable and fair fashion is available in leading department stores everywhere. I also think it’s about long-term partnership and relationships. Not just in the relationships that brands have with their suppliers, but also that buyers have with the brands that they sell, and they curate, because it takes time to educate a consumer as to why a particular brand is important.

Clearly there’s a reason why ethical brands are small, we’re spending money on the product, the innovation in terms of sustainability and we don’t have as much money to spend on marketing and branding as all the big global sportswear, denim wear and clothing brands.

So consumers have to seek out and positively discriminate and buy ethical brands. At the same time, buyers should be doing the same, not expecting the small brands to put the same marketing budget behind their concessions as sometimes I’m asked in this country. Clearly we don’t have the funds, they need to be really telling the story behind the brands and why the product’s different as part of their CSR policies, as part of their sustainability policies. And that’s happening way too little.

I worked with some of the multinationals in the last couple of years to find out what they’re doing. I think the point is that they’ve built their businesses on sweated labor, and so of course they have huge profits to put behind an ethical product offer and to put money behind the branding for that ethical fashion offer.

And whilst it’s really important that they bring their customers on that journey to find sustainability within their own shops, I think for the educated conscious consumer, buying the pioneering brands and supporting really curious authentic initiatives are vital to keep the movement moving forward, because they don’t have the kind of marketing budgets that the multinational brands have.

for the educated conscious consumer, buying the pioneering brands and supporting really curious authentic initiatives are vital to keep the movement moving forward

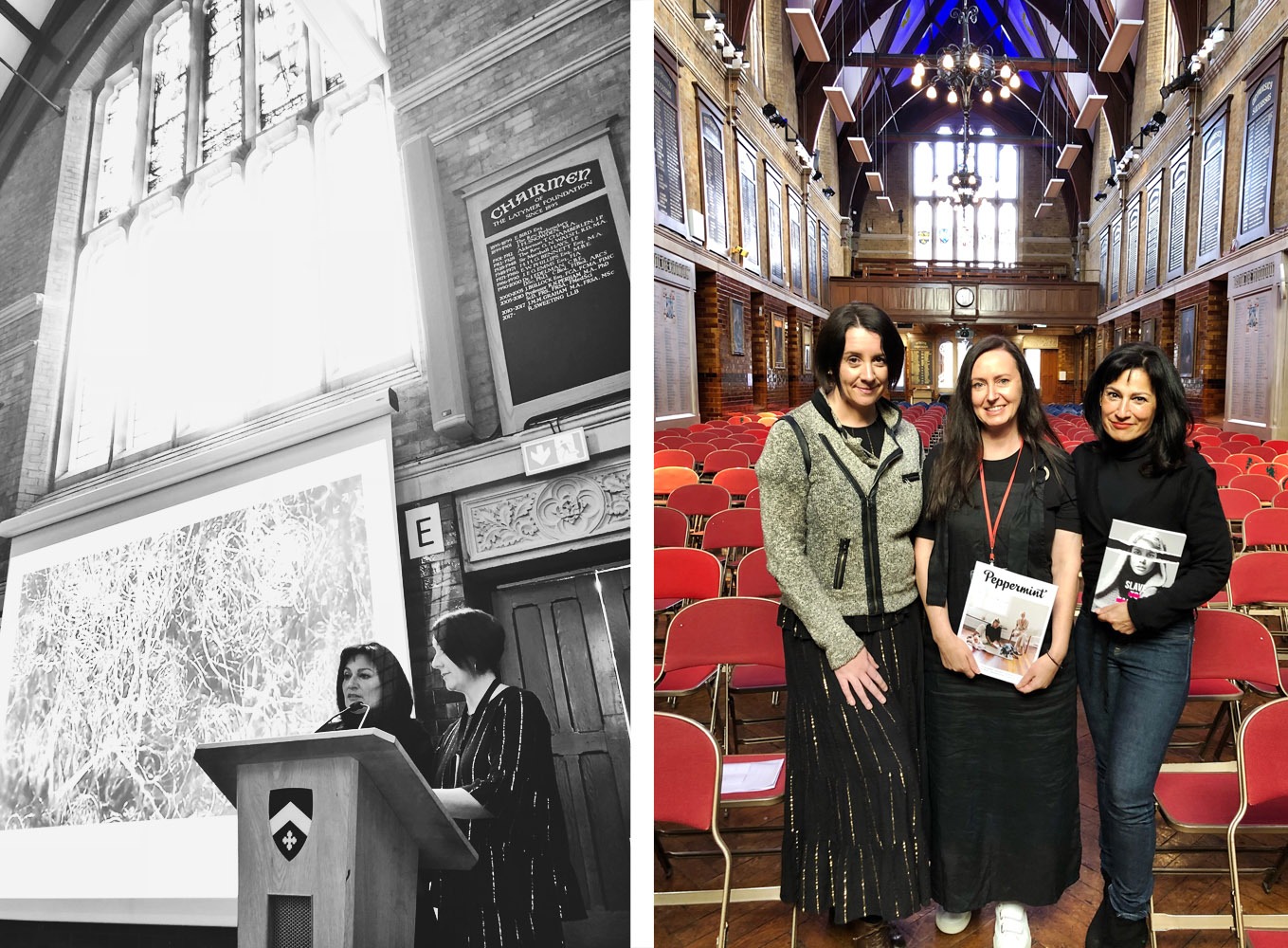

Today I heard you and [environmental author, writer and presenter] Lucy Siegle speaking at a high school – they were very lucky to have such esteemed speakers from the industry! Why is it important to reach the younger generation?

I think there’s a real mutual appreciation. I know Lucy and I really loved speaking to them, and I loved going to their classrooms afterwards and hearing their discussions about sustainability and branding. Getting really smart about business means that they’ll take control of their own consumer decisions.

I remember as a late teen coming across Noam Chomsky’s book, Manufacturing Consent, and it changed my life – I realized that we were really being brainwashed. And I think kids today have unfortunately inherited this mess of a completely faulty economic system that unfortunately my generation and older have put in place.

But wow, it’s so exciting to hear those intelligent questions [from the children], more intelligent actually than from most fashion buyers I must say. So yeah, really, really exciting, and hats off to them!

Getting really smart about business means that they’ll take control of their own consumer decisions.

ABOVE LEFT: SAFIA MINNEY (L) AND LUCY SIEGLE (R) RIGHT: SAFIA AND LUCY WITH KELLEY SHEENAN.

PHOTOS BY KELLEY SHEENAN

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Brighten up your inbox with our not-too-frequent emails featuring Peppermint-related news, events, competitions and more!

explore

More articles

It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas…. Which means we are officially entering party season. Work parties, friend-dos, family get-togethers and then we’re straight into New Year festivities. If you’re lucky enough, you might be staring down the barrel…

Look, I don’t want to make anyone panic but IT’S DECEMBER!!! If you’re planning to give homemade gifts, you’re going to have to act fast. …

Furred, feathered, fishy, scaled… The pets we choose are as diverse as our personalities. (And apparently, quite often we resemble each other.) But they all…

When you hang a painting on a wall, the story stays put. But when you wear a beautifully made garment that may as well be…

Hang out with us on Instagram

“We love that we can bring a hint of imagination and whimsy into everyday life by making ordinary objects fun. We’ve learned to appreciate the little wins and to take a moment for each step we achieve.”

Disillusioned by the realities of fast fashion, design grads Emily May and Sidonie Moore ditched clothing for a business that finds fun in the everyday. Enter @TheNonsenseMaker: a collection of unique homewares, fun wall art, greeting cards and more that breathe life into Emily’s illustrations: “I love the idea of taking real-world objects and changing your perspective in a way that brings magic and whimsy into everyday life!”

In issue 64’s feature ‘It all makes sense’, we chat to the Naarm/Melbourne-based duo about their sustainability philosophy, TV re-runs and their commitment to local makers. At stockists now!

Photos: @MeAndMyGirl

#PeppermintMagazine #TheNonsenseMaker #LocalMakers #SustainableCraft

Any New Year’s resolutions on your list? We love this from @OtterBeeStitching - “be brave enough to suck at something new”.

There’s no points for perfection, but you’ll get a trophy for trying. If nothing else this year, take the leap and try something new.

#OtterBeeStitching #Embroidery #BeBrave #TrySomethingNew #EmbroideryArt

Sunday serving suggestion ☀️

Gorgeous photos from @JolieFemmeStore - who make sweet garments from vintage bedsheets.

#PeppermintMagazine #SlowSunday #SwitchOff #Unplug #ReadAMagazine

A toast to the old you 🥂

We wholeheartedly love this post from the brilliant @EmilyOnLife:

“2026: Reinvent, burn it down, let it go (whatever it is). Year of the Snake it up. Exercise your boundaries, exercise your body, take one teeny step every day towards a life that feels better to be in.

But don’t you dare shit on your old self while you do it.

Hold yourself with reverence and tenderness and respect, because you got you this far. You did your very best with the information and tools you had at the time. You scraped yourself together, you made it work, you survived what felt impossible to survive: again and again and again.

You are perpetually in the process of becoming, whether you can feel it or not, whether or not you add it to your 2026 to-do list.“

Some very wise words from @Damon.Gameau to take us into 2026 🙌🏼

⭐️ We made it!!! ⭐️

Happy New Year, friends. To those who smashed their goals and achieved their dreams, and to those who are crawling over the finish line hoping to never speak of this year again (and everyone else in between): we made it. However you got here is enough. Be proud.

It’s been a tough year for many of us in small business, so here’s to a better year in 2026. We’re forever grateful for all your support and are jumping for joy to still be here bringing you creativity, kindness and community.

We’re also excited to be leaping into the NY with our special release sewing pattern – the Waratah Wrap Dress!

How great are our fabulous models: @Melt.Stitches, @KatieMakesADress and @Tricky.Pockets - and also our incredible Sewing Manager @Laura_The_Maker! 🙌🏼

Ok 2026: let’s do this. 💪🏼

#PeppermintWaratahWrapDress #PeppermintPatterns #SewingPattern #MeMade #WrapDress #WrapDressPattern