Right to Repair: Everything You Need to Know About the New Movement Fighting E-Waste

words EMILY LUSH images UNSPLASH

Electronic waste (e-waste) is the single fastest growing waste stream in the world. According to the UN’s e-waste monitor, we generated a whopping 53.6 million tonnes of e-waste globally in 2019, representing a 21% increase over the course of five years. There are numerous reasons why the volume of e-waste is growing – not least of all conspicuous consumerism, our desire to have the latest and greatest tech at our fingertips. But the reality that electronics are becoming more and more difficult to repair is no small part of the problem either.

In the past few months, Europe, the UK and the US have all made significant strides on ‘Right to Repair’ legislation designed to curb e-waste by giving consumers greater control over electronics. But how far has the movement come and how does Australia compare? Emily Lush takes a look under the hood of ‘Right to Repair’.

In the 2018-2019 financial year, Australians sent an estimated 539,000 tonnes of e-waste to the tip. According to CleanUp.org, the vast majority of our household electronics are destined for landfill: 88% of computers and televisions sold every year wind up as e-waste.

Some of us are guilty of ditching working items in favour of the latest upgrade. But oftentimes, we don’t have much of a choice. When things go awry, replacing your phone or fridge can be more economical (and certainly a lot easier) than repairing it.

How did we get here?

The lifespan of electronics and white goods has been decreasing since the 1950s, when ‘planned obsolescence’ (the idea that products should become obsolete before they fail) first emerged as a principle. Similarly, ‘designing to fail’ is a cynical strategy deployed by many electronics companies in a bid to boost sales.

Even when we’d much prefer to fix something, the monopoly electronics companies have over how, where and when repairs can be made often makes it impossible. Backward compatibility (when manufacturers drop support for otherwise functional devices), use of non-standard or proprietary parts, discontinuing access to spare parts – these are all common ‘tricks’ to make us buy new.

According to the UN’s e-waste monitor, we generated a whopping 53.6 million tonnes of e-waste globally in 2019, representing a 21% increase over the course of five years.

The rise of ‘smart’ technology has only amplified the problem, with items that contain a computer chip notoriously difficult to take apart and repair.

Alongside the issue of e-waste, increased demand for new electronics is putting more strain on raw materials – including rare earth metals. This is in turn associated with a whole host of other issues, from workers’ health to conflict metals and damaging extraction processes.

Enter the ‘Right to Repair’

In the midst of mounting concerns, ‘Right to Repair’ – both a piece of proposed legislation and a consumer-led movement – has been gaining traction.

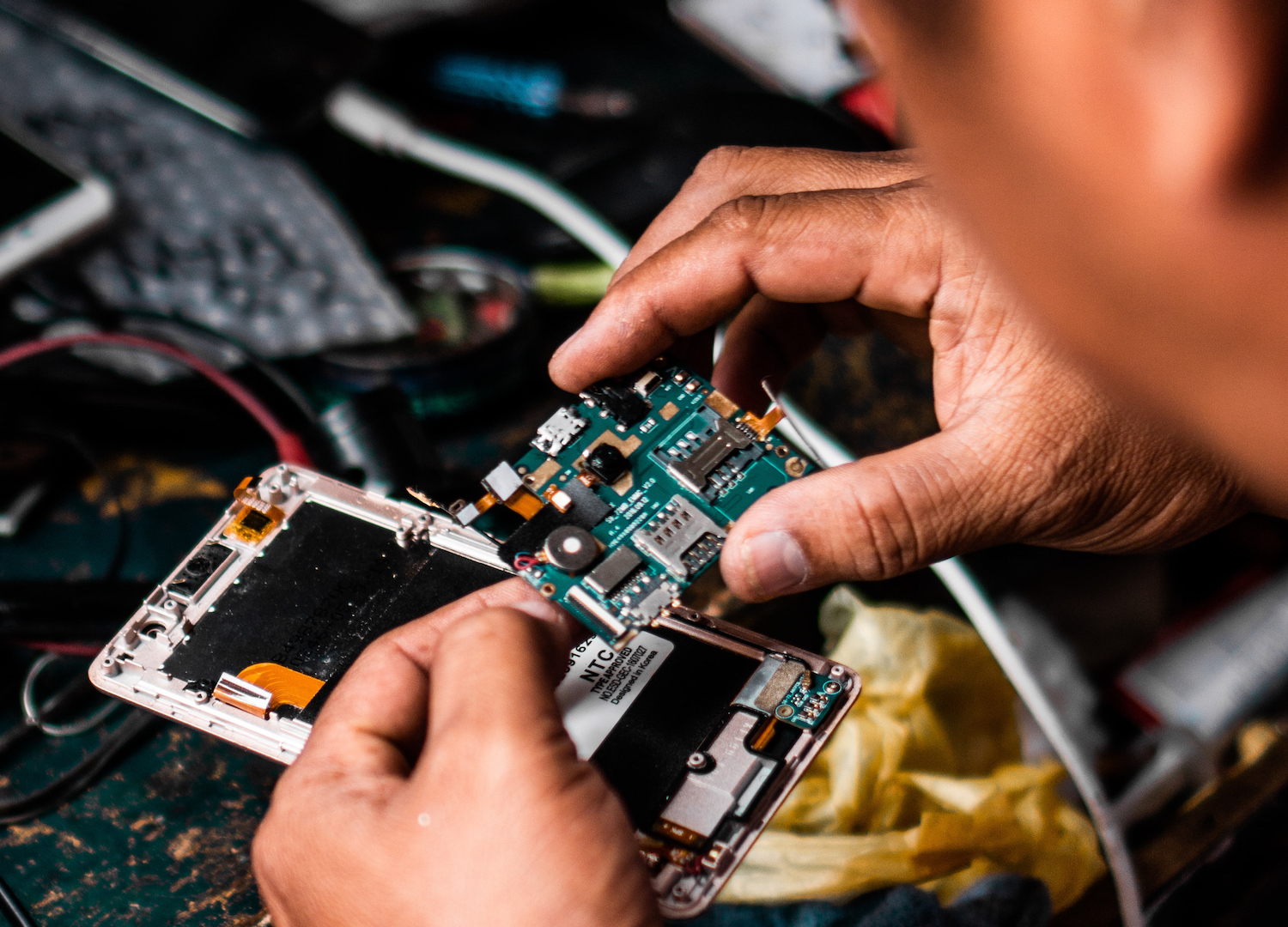

It relies on a simple principle: as the owner of an electronic device, you should be able to repair or modify it yourself, or at least choose a technician to do it for you. Switching a battery, fixing a cracked screen, swapping a faulty hinge – these are all small actions that can significantly increase the lifespan of an item and save it from landfill. Right to Repairers argue that fixing faulty electronics should be as easy and affordable as replacing the sole of a worn-down shoe or mending a split in your favourite trousers.

The Right to Repair movement encompasses everything from farming equipment to vacuums and washing machines, phones, laptops and printers. Through advocating for legislative change, it aims to make information (such as repair manuals and software updates), tools and parts more readily available. The movement also calls for ‘repairability’ to be baked into product design.

Despite concerns over cyber-security and intellectual property, Right to Repair is taking off around the globe, with most agreeing that the pros for our planet in terms of e-waste far outweigh concerns mounted by the tech companies.

READ MORE: SEVEN TECH TOOLS TO OFFSET YOUR ONLINE FOOTPRINT

Who’s leading on Right to Repair?

Right to Repair is a global movement that’s traditionally been centred in Europe. All that changed in the midst of the pandemic.

As hospitals scrambled to repair and maintain ventilator machines, IFixIt and the non-profit Public Interest Research Group joined forces to release the largest collection of manuals and service guides for medical equipment ever published. This filled the information gap left by manufacturers, allowing medical staff to make their own repairs on essential equipment – a move that ultimately helped save lives.

Since then, Right to Repair has been gaining momentum. On 1 July, the UK introduced rules requiring electronics manufacturers to make spare parts for household electronics more readily available to the public. The so-called ‘Right to Repair Law’ also asks companies to supply professional repair shops with parts needed for more complex jobs.

On 9 July, US President Biden signed an Executive Order instructing the Federal Trade Commission to design rules to make owner-repairs easier. On top of that, a national bill has been filed in congress, and the majority of US states have each proposed their own bills, with Massachusetts the first state to vote Right to Repair into law.

Giving Australians the Right to Repair

Australia is lagging behind the US and Europe on Right to Repair, but it’s not too late to catch up. The demand is there: according to Choice, 85% of Australians say that product longevity is important to them and 73% agree that repairability is important.

On 11 June, the Productivity Commission released a draft report on Right to Repair in Australia. Drawing on more than 300 submissions and comments from the public, it revealed frustration and discontent among consumers at the current state of the electronics repair industry.

The report recommends the ACCC introduce a “minimum expected durability for categories of household products”, which could pave the way for a labelling system that gives items a repairability score, similar to the one that’s currently used in France.

85% of Australians say that product longevity is important to them and 73% agree that repairability is important.

Laws that ban manufacturers from voiding warranties if customers use unauthorised repair services are also under consideration, along with changes to copyright law that would make it easier for third-parties to publish manuals and access pertinent manufacturer data when fixing items.

The draft report is a prelude to public hearings (now underway), with a final report due to be handed down to the Government by October.