Ocean Optimism: Restoring the Great Barrier Reef One Coral Fragment at a Time

- Words by Peppermint

The decline of the Great Barrier Reef has become a household topic as news of mass bleaching events flood the media and climate strikes take to our streets. But with the expansion of innovative coral nurseries in Australia, there’s a solution in sight.

This month, the Reef Restoration Foundation – a not-for-profit social enterprise based in Far North Queensland – will install 10 coral tree frames at a new nursery, pending permit approval. The nursery, once installed, will be the foundation’s third; one containing 20 trees, is submerged 200 metres from Fitzroy Island and another, containing 10, is located at Hastings Reef. Each new tree brings a tidal wave of hope for the restoration of this natural wonder.

The foundation launched after the back-to-back coral bleaching events of 2016 and 2017, when soaring sea temperatures devastated two-thirds of our national treasure. A report published in the journal Nature in 2019 revealed that as the gap between bleaching episodes continues to shrink, so too does the window for corals to recover naturally.

The number of new corals settling on the Great Barrier Reef declined by 89 percent following the unprecedented loss of adult corals from global warming in 2016 and 2017.

“Dead corals don’t make babies,” lead author Professor Terry Hughes said at the time. “The number of new corals settling on the Great Barrier Reef declined by 89 percent following the unprecedented loss of adult corals from global warming in 2016 and 2017.”

Recognising the need for urgent action and intervention, the team of scientists and volunteers behind the Reef Restoration Foundation collaborated with coral conservation projects that were successful in Florida and the Caribbean to create the first coral farms Down Under.

Since late 2017, they have grown and out-planted 2000 coral colonies on the Great Barrier Reef, with 3000 resilient corals currently growing on their steel trees. This is a small but significant paddle in the right direction.

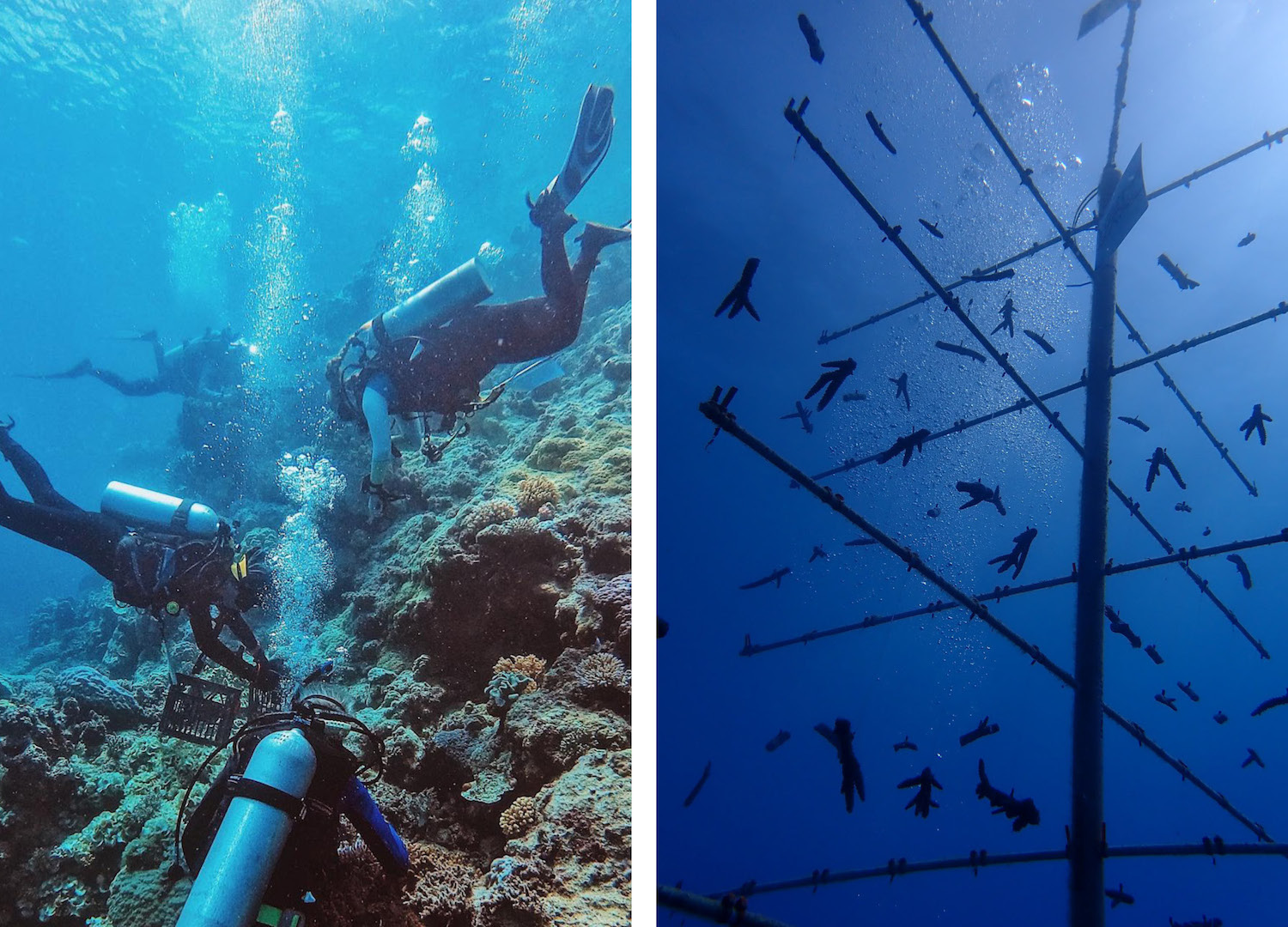

IMAGE: FITZROY ISLAND. PHOTO BY GARY MCKENNA.

So, how does it work?

Anyone with a green thumb will be familiar with the process of taking cuttings from a healthy plant to grow a new one elsewhere. Propagating coral follows a similar method, albeit underwater.

Marine biologist and senior member of the foundation, Azri Saparwan, says the first step involved “surveying Fitzroy Island for coral colonies that survived the mass bleaching event of 2017. If they survived, it meant they were resistant to warming temperatures”.

Once identified, fragments (no larger than 10% of the total coral size of each individual donor colony) from a specified section of reef were collected by volunteers and cut into mother colonies and fragments the size of a finger. These were then attached to horizontal bars on underwater steel frames to grow in size and strength, hung like ornaments on a Christmas tree.

“Corals are able to reproduce asexually through propagation,” Azri explains. After six to 12 months of growth, half of the coral fragments are removed from the nursery and out-planted to the reef using underwater glue, increasing coral coverage and introducing more heat-tolerant colonies to the marine ecosystem.

“The other half are propagated again into smaller pieces, so there are no more collections from the wild,” Azri says. This means that these corals will regrow on the frames, ensuring a continuous cycle and creating thousands of new corals from a single cutting.

IMAGES: DIVERS COLLECTING CORAL FRAGMENTS; A STEEL CORAL TREE.

Is it enough to save the Great Barrier Reef?

Due to the effects of climate change, coral reefs have changed so dramatically that conservation efforts can no longer aim to restore the marine environment to its historical splendour. The new goal? To preserve the reef in its current state and ensure its survival for many generations to come.

There’s only one way to fix this problem and that’s to tackle the root cause of global heating by reducing net greenhouse gas emissions to zero as quickly as possible.

Another report co-authored by Terry last year, Rebuilding Marine Life, stated that the aim of conservation interventions is to “rebuild depleted populations rather than sustaining the status quo”, but more needs to be done on a global scale.

“There’s only one way to fix this problem,” he warns, “and that’s to tackle the root cause of global heating by reducing net greenhouse gas emissions to zero as quickly as possible.” Should climate change prevail, the Great Barrier Reef will cease to exist by the end of the century. Every action – and coral fragment – counts.

IMAGE: SPECIALIST NURSERY DIVER.

What can you do?

“No matter where you are in the world, every effort to control global warming will help, from choosing a sustainable energy provider, to walking or cycling to work, saying no to single-use plastics and supporting non-profit organisations like us,” Azri says.

To support the Reef Restoration Foundation, it’s as easy as adopting a coral via their website. With each adoption – starting at $50 for a single coral – the team can plant another colony and keep fighting for the future of the Great Barrier Reef, one coral fragment at a time.

words KAYLA WRATTEN images COURTESY OF REEF RESTORATION FOUNDATION

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Brighten up your inbox with our not-too-frequent emails featuring Peppermint-related news, events, competitions and more!

explore

More articles

Look, I don’t want to make anyone panic but IT’S DECEMBER!!! If you’re planning to give homemade gifts, you’re going to have to act fast. …

Hang out with us on Instagram

“In the 1940’s, Norwegians made and wore red pointed hats with a tassel as a form of visual protest against Nazi occupation of their country. Within two years, the Nazis made these protest hats illegal and punishable by law to wear, make, or distribute. As purveyors of traditional craft, we felt it appropriate to revisit this design.”

Crafters have often been at the heart of many protest movements, often serving as a powerful means of political expression. @NeedleAndSkein, a yarn store in Minnesota, are helping to mobilise the craftivists of the world with a ‘Melt The Ice’ knitting pattern created by @Yarn_Cult (with a crochet pattern too), as a way of peaceful protest.

The proceeds from the $5 pattern will go to local immigrant aid organisations – or you can donate without buying the pattern.

Raise those needles, folks – art and craft can change the world. 🧶

Link in bio for the pattern.

Images: @Gather_Fiber @NeedleAndSkein @a2ina2 @KyraGiggles Sandi.204 @WhatTracyMakes AllieKnitsAway Auntabwi2

#MeltTheIce #Craftivism #Knitting #CraftForChange

TWO WEEKS TO GO! 🤩

"The most important shift is moving from volume-led buying to value-led curation – choosing fewer, better products with strong ethics, considered production and meaningful stories. Retailers have real influence here: what you buy signals what you stand for. At Life Instyle, this means using the event to discover and invest in small-scale, planet-considerate brands that align with your values and your customer’s conscience. Consumers don’t need more things; they need better things, and retailers play a key role in selecting, contextualising, and championing why those products matter."

Only two more weeks until @Life_Instyle – Australia`s leading boutique retail trade show. If you own a store, don`t miss this event! Connect with designers, source exquisite – and mindful – products, and see firsthand why this is Australia’s go-to trade show for creatives and retailers alike. And it`s free! ✨️

Life Instyle – Sydney/Eora Country

14-17 February 2026

ICC, Darling Harbour

Photos: @Samsette

#LifeInstyle #SustainableShopping #SustainableShop #RetailTradeEvent

Calling all sewists! 📞

Have you made the Peppermint Waratah Wrap Dress yet? Call *1800 I NEED THIS NOW to get making!

This gorgeous green number was modelled (and made) by the fabulous Lisa of @Tricky.Pockets 🙌🏼

If you need a nudge, @ePrintOnline are offering Peppermint sewists a huge 🌟 30% off ALL A0 printing 🌟 when you purchase the Special Release Waratah Wrap Dress pattern – how generous is that?!

Head to the link in bio now 📞

*Not a real number in case that wasn`t clear 😂

#PeppermintWaratahWrapDress #PeppermintPatterns #SewingPattern #WrapDress #WrapDressPattern

8 Things to Know About January 26 - from @ClothingTheGaps:

Before you celebrate, take the time to learn the truth. January 26 is not a day of unity it’s a Day of Mourning and Survival for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It marks the beginning of invasion, dispossession, and ongoing colonial violence. It’s time for truth-telling, not whitewashed history.

Stand in solidarity. Learn. Reflect. Act.

✊🏽 Blog written by Yorta Yorta woman Taneshia Atkinson.

🔗 Link in bio of @ClothingTheGaps to read the full blog

#ChangeTheDate #InvasionDay #SurvivalDay #AlwaysWasAlwaysWillBe #ClothingTheGaps

As the world careens towards AI seeping into our feeds, finds and even friend-zones, it`s becoming increasingly hard to ignore.

We just wanted to say that here at Peppermint, we are choosing to not print or publish AI-generated art, photos, words, videos or content.

Merriam-Webster’s human editors chose `slop` as the 2025 Word of the Year – they define it as “digital content of low quality that is produced usually in quantity by means of artificial intelligence.” The problem is, as AI increases in quality, it`s becoming more and more difficult to ascertain what`s real and what`s not.

Let`s be clear here, AI absolutely has its place in science, in climate modelling, in medical breakthroughs, in many places... but not in replacing the work of artists, writers and creatives.

Can we guarantee that everything we publish is AI-free? Honestly, not really. We know we are not using it to create content, but we are also relying on the artists, makers and contributors we work with, as well as our advertisers, to supply imagery, artwork or words created by humans. AI features are also creeping into programs and apps too, making it difficult to navigate. But we will do our best to avoid it and make a stand for the artists and creatives who have had their work stolen and used to train AI machines, and those who are now losing work as they are replaced by this energy-sapping, environment-destroying magic wand.

Could using it help our productivity and bottom line? Sure. And as a small business in a difficult landscape, that`s a hard one to turn down. We know other publishers who use AI to write stories, create recipes, produce photo shoots... but this one is important to us.

`Touch grass` was also a Merriam-Webster Word of the Year. We`ll happily stick with that as a theme, thanks very much. 🌿

If your fingers are twitching for some crafting, take a peep at this massive list of marvellous makes that can be whipped up in a flash, put together by our Sewing Manager Laura. Ok yes, it was originally a roundup we created for easy Christmas gifts, but now it can be your blueprint for easy craft wins to go on your 2026 making must-do list!

If money and time are slim for you right now – as they are for many of us – these 22 projects will help you avoid the chaos and consumerism of the malls, scratch that creative itch and produce a fun me-made make that won’t break the bank.

Link in bio! 🪡🎨✂️

#PeppermintMagazine #MeMadeGifts #DIYs #EasyWins