Still Talking About a Fashion Revolution: 10 Years On From Rana Plaza

- Words by Peppermint

words ATHINA GREENHALGH

It’s been 10 years since the Rana Plaza factory building in Bangladesh collapsed, killing more than 1100 and injuring 2500. It was a tragedy that sent shockwaves around the world, drawing international media attention, and exposing to the public uncomfortable truths about how our clothes are made.

It was not the first industrial disaster to hit the fashion industry, and sadly it hasn’t been the last, but Rana Plaza started a conversation. It shone a light on not only the unsafe working conditions to which workers were often exposed but a suite of other concerns too including forced overtime, poverty pay, instances of modern slavery, child labour and limited freedom of association, as well as the environmental impact of fashion.

As Fashion Revolution Week kicks off, below we reflect on the 10 years that have passed since Rana Plaza – exploring what progress has been made to advocate for garment workers and ensure no one dies for fashion.

Calling for a #FashionRevolution

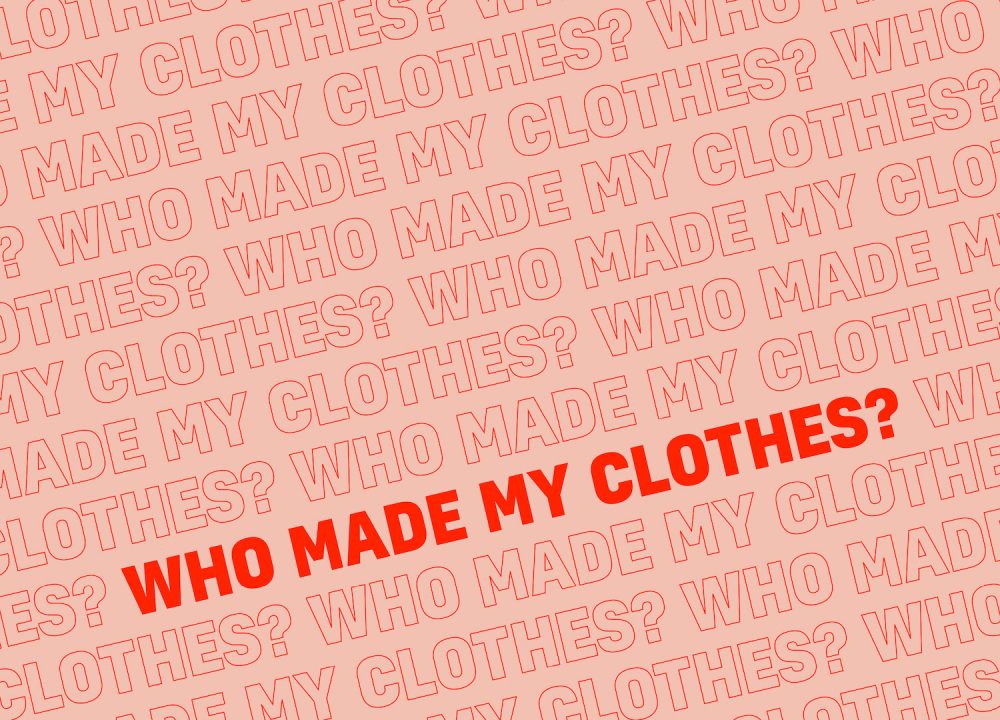

Founded by fashion designers and social advocates Carry Somers and Orsola de Castro, the annual Fashion Revolution Week campaign was established in the wake of Rana Plaza. Mustering consumers to become social campaigners, the movement encourages shoppers to ask their favourite brands “Who made my clothes?” – a simple call to action that puts significant pressure on brands to bridge the gap between garment workers and consumers.

Now, Fashion Revolution’s Transparency Index reviews 250 of the world’s largest brands, offering an annual snapshot of the industry’s progress. Of course, transparency doesn’t equal sustainability, but it is the first step in brands taking accountability and responsibility for their impact.

In the 2022 release, the index found only 48% of brands disclosed their first-tier suppliers (these are the suppliers only one step removed from the brand, where our clothes are sewn and finished). Details became cloudier further down the supply chain, where a mere 12% of brands disclosed some of their raw materials suppliers. Clearly, there is a long way to go, but Fashion Revolution says that brands are much more open to sharing this information than they were previously, reflecting that in 2017, 0% of brands reviewed were disclosing raw materials suppliers.

While up to 91% of luxury brands have committed to goals such as sourcing sustainable materials, protecting biodiversity and using renewable energy, only 35% publicly encourage suppliers to allow trade unions to form.

In terms of living wages, disappointingly the report shows no progress in the past three years, with just 27% of brands disclosing their approach to achieving living wages for supply chain workers. They report that policy is consistently the area where brands achieve the highest average score, and yet when it comes to taking action or disclosure of practices, even the highest-ranking brands are not meeting expectations.

Vogue Business, in their recent index of luxury fashion brands, also found a significant imbalance between the industry’s labour rights and environmental goals, suggesting that both are not being prioritised equally: “While up to 91% of luxury brands have committed to goals such as sourcing sustainable materials, protecting biodiversity and using renewable energy, only 35% publicly encourage suppliers to allow trade unions to form, according to the index. Just over half of brands say they ensure workers in their supply chain are paid at least minimum wage.”

Landmark collaboration, regulation, and legislation

It’s impossible to talk about Rana Plaza without talking about the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, which was established in response to the disaster. Now updated to the International Accord, this agreement between local trade unions and 192 signatory brands enforces independent workplace safety audits, adequate safety training for staff and protects the worker’s right to raise safety concerns. The legally binding nature of the accord, as well as the fact that it was backed by all key local labour rights bodies, made it a landmark, trailblazing agreement for the industry. This year, Pakistan is preparing to adopt its own similar agreement with 35 brands on board so far.

Brands and consumers cannot re-engineer the fashion industry on their own which is why it’s promising to see governments step up to the plate by introducing legislation that targets the industry’s biggest players.

The United Kingdom Modern Slavery Act (2015) and Australian Modern Slavery Act (2018) require large brands to report on the risk of modern slavery within their supply chains, as well as the actions they are taking to address it. Modern slavery and worker exploitation are not the same thing, but these regulations will require businesses to take a magnifying glass to their supply chains – the first step in identifying exploitation of any kind.

While there will never be a silver lining to Rana Plaza, we can’t ignore the legacy this event left, influencing change at a government, industry and consumer level – driving sustainability out of the shadows to the forefront of the conversation.

There is also pending legislation in the EU (the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive) as well as in New York (the Fashion Sustainability and Social Accountability Act) which will require large brands to report on both their social and environmental impact.

Further, the Garment Worker Protection Act in California has been effective since 2022, demanding garment workers receive a standard hourly rate rather than piece-rate pay. Fashion Revolution, Fair Wear, and ASN Bank have also teamed up to form the Good Clothes, Fair Pay campaign in the EU, which demands living wage legislation across the garment, textile and footwear sectors.

While there will never be a silver lining to Rana Plaza, we can’t ignore the legacy this event left, influencing change at a government, industry and consumer level – driving sustainability out of the shadows to the forefront of the conversation. Even still, it’s clear that nowhere near enough has been done to protect the people that make our clothes.

Get Involved

Consumers play an important role in driving positive change. Here are a few ways you can get involved this Fashion Revolution Week:

ONE // Sign the manifesto for a Fashion Revolution

Join together with like-minded fashion lovers globally in signing the Fashion Revolution Manifesto which also includes a range of small but significant steps you can take to take action.

TWO // Ask “Who made my clothes?”

Take to social media, email or even the post office to let your favourite brands know, while you like their clothes, you’d really love to know that they were made in a way that reflects your values.

THREE // Gather ‘round

Keep an eye out for in-person or online Fashion Revolution events in your neighbourhood.

WANT MORE SUSTAINABLE FASHION CONTENT? RIGHT THIS WAY!

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Brighten up your inbox with our not-too-frequent emails featuring Peppermint-related news, events, competitions and more!

explore

More articles

Look, I don’t want to make anyone panic but IT’S DECEMBER!!! If you’re planning to give homemade gifts, you’re going to have to act fast. …

Hang out with us on Instagram

🌻 The Paddington 🌻

This is a much-loved staple, created for Issue 50 in 2021. We love seeing the #PeppermintPaddingtonTop continually popping up in our feeds!

How stunning is our model Elon MelaninGoddessEfon – she told us it was one of the first times she had been asked to come to a shoot with her natural hair. 🌻

We worked with South African patternmaker Sarah Steenkamp of @FrenchNavyNow_ to create this wardrobe essential – the perfect puff-sleeve blouse. Raglan sleeves make it the ultimate beginner sew, plus the gorgeous back buttons let you add your own personal twist.

Pattern via the link in bio! 🪡

Photos: @KelleySheenan

Fabric: @Spoonflower

Model: MelaninGoddessEfon

“In the 1940’s, Norwegians made and wore red pointed hats with a tassel as a form of visual protest against Nazi occupation of their country. Within two years, the Nazis made these protest hats illegal and punishable by law to wear, make, or distribute. As purveyors of traditional craft, we felt it appropriate to revisit this design.”

Crafters have often been at the heart of many protest movements, often serving as a powerful means of political expression. @NeedleAndSkein, a yarn store in Minnesota, are helping to mobilise the craftivists of the world with a ‘Melt The Ice’ knitting pattern created by @Yarn_Cult (with a crochet pattern too), as a way of peaceful protest.

The proceeds from the $5 pattern will go to local immigrant aid organisations – or you can donate without buying the pattern.

Raise those needles, folks – art and craft can change the world. 🧶

Link in bio for the pattern.

Images: @Gather_Fiber @NeedleAndSkein @a2ina2 @KyraGiggles Sandi.204 @WhatTracyMakes AllieKnitsAway Auntabwi2

#MeltTheIce #Craftivism #Knitting #CraftForChange

TWO WEEKS TO GO! 🤩

"The most important shift is moving from volume-led buying to value-led curation – choosing fewer, better products with strong ethics, considered production and meaningful stories. Retailers have real influence here: what you buy signals what you stand for. At Life Instyle, this means using the event to discover and invest in small-scale, planet-considerate brands that align with your values and your customer’s conscience. Consumers don’t need more things; they need better things, and retailers play a key role in selecting, contextualising, and championing why those products matter."

Only two more weeks until @Life_Instyle – Australia`s leading boutique retail trade show. If you own a store, don`t miss this event! Connect with designers, source exquisite – and mindful – products, and see firsthand why this is Australia’s go-to trade show for creatives and retailers alike. And it`s free! ✨️

Life Instyle – Sydney/Eora Country

14-17 February 2026

ICC, Darling Harbour

Photos: @Samsette

#LifeInstyle #SustainableShopping #SustainableShop #RetailTradeEvent

Calling all sewists! 📞

Have you made the Peppermint Waratah Wrap Dress yet? Call *1800 I NEED THIS NOW to get making!

This gorgeous green number was modelled (and made) by the fabulous Lisa of @Tricky.Pockets 🙌🏼

If you need a nudge, @ePrintOnline are offering Peppermint sewists a huge 🌟 30% off ALL A0 printing 🌟 when you purchase the Special Release Waratah Wrap Dress pattern – how generous is that?!

Head to the link in bio now 📞

*Not a real number in case that wasn`t clear 😂

#PeppermintWaratahWrapDress #PeppermintPatterns #SewingPattern #WrapDress #WrapDressPattern

8 Things to Know About January 26 - from @ClothingTheGaps:

Before you celebrate, take the time to learn the truth. January 26 is not a day of unity it’s a Day of Mourning and Survival for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It marks the beginning of invasion, dispossession, and ongoing colonial violence. It’s time for truth-telling, not whitewashed history.

Stand in solidarity. Learn. Reflect. Act.

✊🏽 Blog written by Yorta Yorta woman Taneshia Atkinson.

🔗 Link in bio of @ClothingTheGaps to read the full blog

#ChangeTheDate #InvasionDay #SurvivalDay #AlwaysWasAlwaysWillBe #ClothingTheGaps

As the world careens towards AI seeping into our feeds, finds and even friend-zones, it`s becoming increasingly hard to ignore.

We just wanted to say that here at Peppermint, we are choosing to not print or publish AI-generated art, photos, words, videos or content.

Merriam-Webster’s human editors chose `slop` as the 2025 Word of the Year – they define it as “digital content of low quality that is produced usually in quantity by means of artificial intelligence.” The problem is, as AI increases in quality, it`s becoming more and more difficult to ascertain what`s real and what`s not.

Let`s be clear here, AI absolutely has its place in science, in climate modelling, in medical breakthroughs, in many places... but not in replacing the work of artists, writers and creatives.

Can we guarantee that everything we publish is AI-free? Honestly, not really. We know we are not using it to create content, but we are also relying on the artists, makers and contributors we work with, as well as our advertisers, to supply imagery, artwork or words created by humans. AI features are also creeping into programs and apps too, making it difficult to navigate. But we will do our best to avoid it and make a stand for the artists and creatives who have had their work stolen and used to train AI machines, and those who are now losing work as they are replaced by this energy-sapping, environment-destroying magic wand.

Could using it help our productivity and bottom line? Sure. And as a small business in a difficult landscape, that`s a hard one to turn down. We know other publishers who use AI to write stories, create recipes, produce photo shoots... but this one is important to us.

`Touch grass` was also a Merriam-Webster Word of the Year. We`ll happily stick with that as a theme, thanks very much. 🌿