This IPCC Report Is the Most Sobering Yet – Here’s What You Need to Know

Earth has warmed 1.09°C since pre-industrial times and many changes such as sea-level rise and glacier melt are now virtually irreversible, according to the most sobering report yet by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The report also found escape from human-caused climate change is no longer possible. Climate change is now affecting every continent, region and ocean on Earth, and every facet of the weather.

The long-awaited report is the sixth assessment of its kind since the panel was formed in 1988. It will give world leaders the most timely, accurate information about climate change ahead of a crucial international summit in Glasgow, Scotland in November.

The IPCC is the peak climate science body of the United Nations and the World Meteorological Organisation. It is the global authority on the state of Earth’s climate and how human activities affect it. We are authors of the latest IPCC report and have drawn from the work of thousands of scientists from around the world to produce this new assessment.

Sadly, there is hardly any good news in the 3900 pages of text released today. But there is still time to avert the worst damage, if humanity chooses to.

Pep Canadell, Chief research scientist, Climate Science Centre, CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere; and Executive Director, Global Carbon Project, CSIRO; Joelle Gergis, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, Australian National University; Malte Meinshausen, A/Prof., School of Earth Sciences, The University of Melbourne; Mark Hemer, Principal Research Scientist, Oceans and Atmosphere, CSIRO, and Michael Grose, Climate projections scientist, CSIRO.

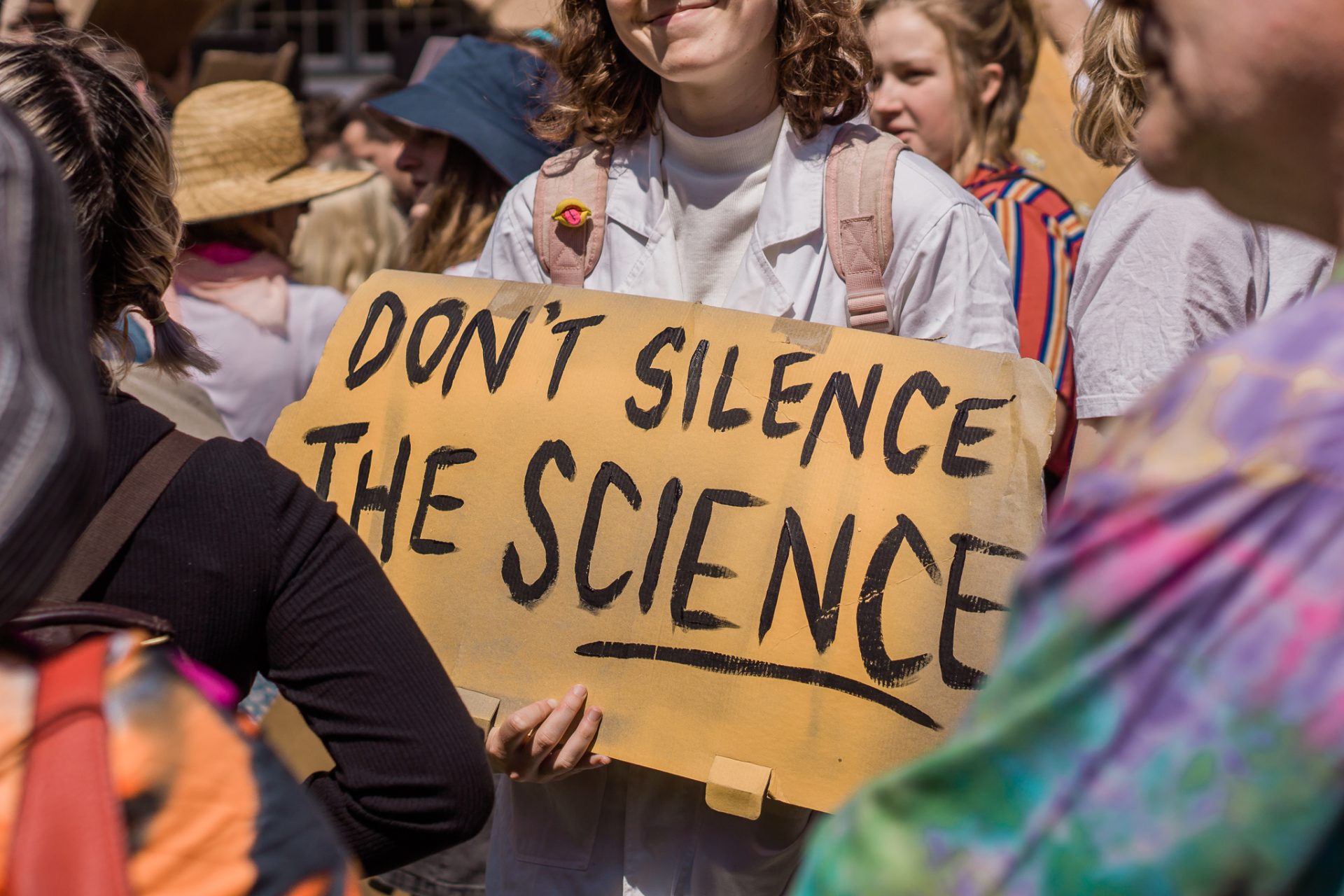

top image 2019 SCHOOL STRIKE FOR CLIMATE. PHOTO BY KELLEY SHEENAN

image ANDREA CREATIVE / PEXELS

It’s unequivocal: humans are warming the planet

For the first time, the IPCC states unequivocally – leaving absolutely no room for doubt – humans are responsible for the observed warming of the atmosphere, lands and oceans.

The IPCC finds Earth’s global surface temperature warmed 1.09°C between 1850-1900 and the last decade. This is 0.29°C warmer than in the previous IPCC report in 2013. (It should be noted that 0.1°C of the increase is due to data improvements.)

Read more: Monday’s IPCC report is a really big deal for climate change. So what is it? And why should we trust it?

The IPCC recognises the role of natural changes to the Earth’s climate. However, it finds 1.07°C of the 1.09°C warming is due to greenhouse gases associated with human activities. In other words, pretty much all global warming is due to humans.

Global surface temperature has warmed faster since 1970 than in any other 50-year period over at least the last 2000 years, with the warming also reaching ocean depths below 2000 metres.

The IPCC says human activities have also affected global precipitation (rain and snow). Since 1950, total global precipitation has increased, but while some regions have become wetter, others have become drier.

The frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events have increased over most land areas. This is because the warmer atmosphere is able to hold more moisture – about 7% more for each additional degree of temperature – which makes wet seasons and rainfall events wetter.

image PIXABAY / PEXELS

Higher concentrations of CO2, growing faster

Present-day global concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) are higher and rising faster than at any time in at least the past two million years.

The speed at which atmospheric CO2 has increased since the industrial revolution (1750) is at least 10 times faster than at any other time during the last 800,000 years, and between four and five times faster than during the last 56 million years.

About 85% of CO2 emissions are from burning fossil fuels. The remaining 15% are generated from land use change, such as deforestation and degradation.

Read more: More livestock, more carbon dioxide, less ice: the world’s climate change progress since 2019 is (mostly) bad news

Concentrations of other greenhouse gases are not doing any better. Both methane and nitrous oxide, the second and third biggest contributors to global warming after CO2, have also increased more quickly.

Methane emissions from human activities largely come from livestock and the fossil fuel industry. Nitrous oxide emissions largely come from the use of nitrogen fertiliser on crops.

Extreme weather on the rise

Hot extremes, heatwaves and heavy rain have also become more frequent and intense across most land regions since 1950, the IPCC confirms.

The report highlights that some recently observed hot extremes, such as the Australian summer of 2012–2013, would have been extremely unlikely without human influence on the climate.

Human influence has also been detected for the first time in compounded extreme events. For example, incidences of heatwaves, droughts and fire weather happening at the same time are now more frequent. These compound events have been seen in Australia, Southern Europe, Northern Eurasia, parts of the Americas and African tropical forests.

Oceans: hotter, higher and more acidic

Oceans absorb 91% of the energy from the increased atmospheric greenhouse gases. This has led to ocean warming and more marine heatwaves, particularly over the past 15 years.

Marine heatwaves cause the mass death of marine life, such as from coral bleaching events. They also cause algal blooms and shifts in the composition of species. Even if the world restricts warming to 1.5-2°C, as is consistent with the Paris Agreement, marine heatwaves will become four times more frequent by the end of the century.

Read more: Watching a coral reef die as climate change devastates one of the most pristine tropical island areas on Earth

Melting ice sheets and glaciers, along with the expansion of the ocean as it warms, have led to a global mean sea level increase of 0.2 metres between 1901 and 2018. But, importantly, the speed sea level is rising is accelerating: 1.3 millimetres per year during 1901-1971, 1.9mm per year during 1971-2006, and 3.7mm per year during 2006-2018.

Ocean acidification, caused by the uptake of CO2, has occurred over all oceans and is reaching depths beyond 2000m in the Southern Ocean and North Atlantic.

image RON LACH / PEXELS

Many changes are already irreversible

The IPCC says if Earth’s climate was stabilised soon, some climate change-induced damage could not be reversed within centuries, or even millennia. For example, global warming of 2°C this century will lead to average global sea level rise of between two and six metres over 2000 years, and much more for higher emission scenarios.

Globally, glaciers have been synchronously retreating since 1950 and are projected to continue to melt for decades after the global temperature is stabilised. Meanwhile the acidification of the deep ocean will remain for thousands of years after CO2 emissions cease.

Read more: We mapped the world’s frozen peatlands – what we found was very worrying

The report does not identify any possible abrupt changes that would lead to an acceleration of global warming during this century – but does not rule out such possibilities.

The prospect of permafrost (frozen soils) in Alaska, Canada and Russia crossing a tipping point has been widely discussed. The concern is that as frozen ground thaws, large amounts of carbon accumulated over thousands of years from dead plants and animals could be released as they decompose.

The report does not identify any globally significant abrupt change in these regions over this century, based on currently available evidence. However, it projects permafrost areas will release about 66 billion tonnes of CO2 for each additional degree of warming. These emissions are irreversible during this century under all warming scenarios.

How we can stabilise the climate

Earth’s surface temperature will continue to increase until at least 2050 under all emissions scenarios considered in the report. The assessment shows Earth could well exceed the 1.5°C warming limit by early 2030s.

If we reduce emissions sufficiently, there is only a 50% chance global temperature rise will stay around 1.5°C (including a temporary overshoot of up to 0.1°C). To get Earth back to below 1.5°C warming, CO2 would need to be removed from the atmosphere using negative emissions technologies or nature-based solutions.

Global warming stays below 2°C during this century only under scenarios where CO2 emissions reach net-zero around or after 2050.

Read more: We’ve made progress to curb global emissions. But it’s a fraction of what’s needed

The IPCC analysed future climate projections from dozens of climate models, produced by more than 50 modelling centres around the world. It showed global average surface temperature rises between 1-1.8°C and 3.3-5.7°C this century above pre-industrial levels for the lowest and highest emission scenarios, respectively. The exact increase the world experiences will depend on how much more greenhouse gases are emitted.

The report states, with high certainty, that to stabilise the climate, CO2 emissions must reach net zero, and other greenhouse gas emissions must decline significantly.

We also know, for a given temperature target, there’s a finite amount of carbon we can emit before reaching net zero emissions. To have a 50:50 chance of halting warming at around 1.5°C, this quantity is about 500 billion tonnes of CO2.

At current levels of CO2 emissions this “carbon budget” would be used up within 12 years. Exhausting the budget will take longer if emissions begin to decline.

The IPCC’s latest findings are alarming. But no physical or environmental impediments exist to hold warming to well below 2°C and limit it to around 1.5°C – the globally agreed goals of the Paris Agreement. Humanity, however, must choose to act.