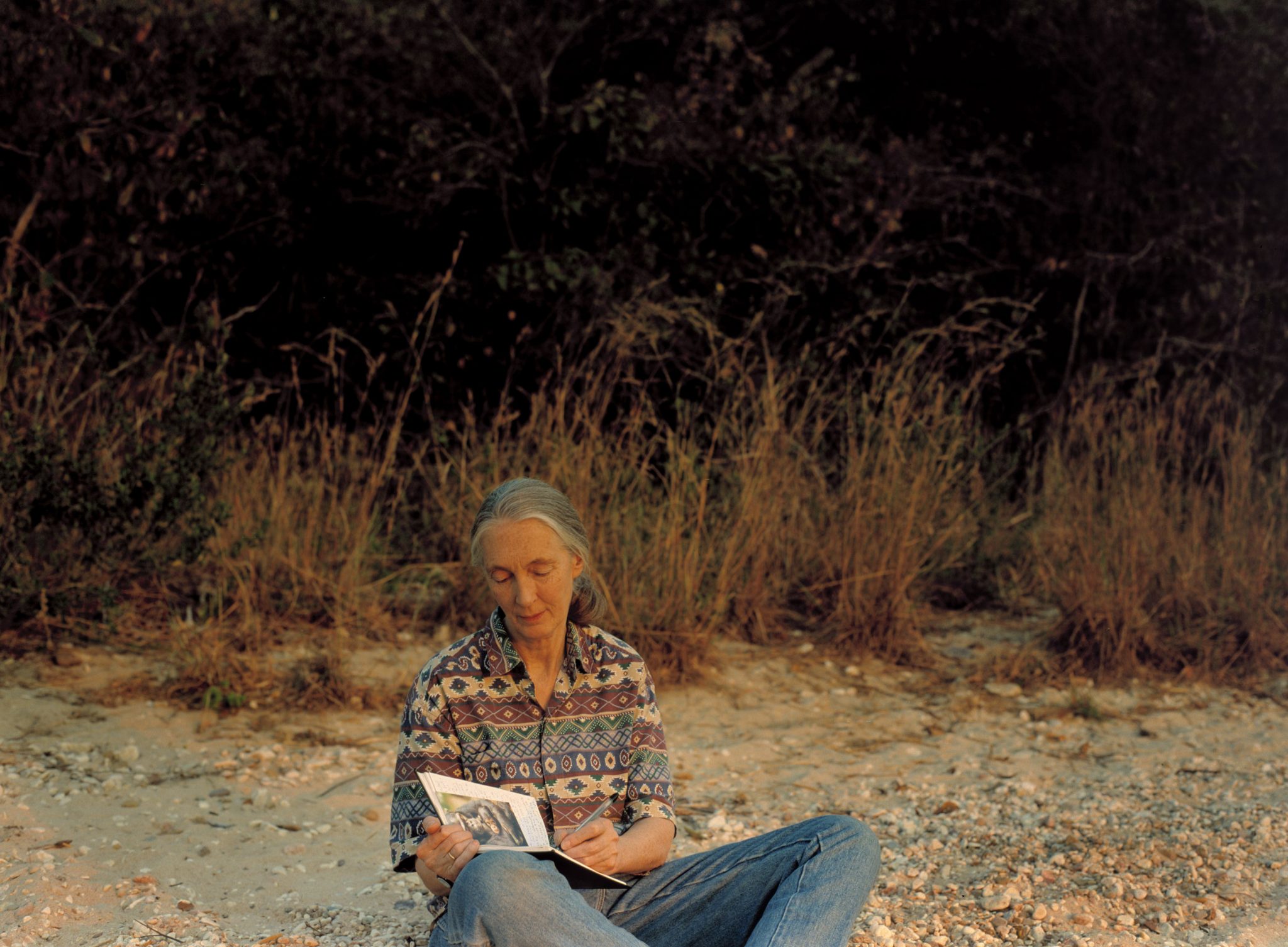

From the Archives // Jane Goodall

Jane Goodall’s favourite toy as a child was a plush chimpanzee given to her by her father after a baby chimpanzee was born at London Zoo. Goodall was enamoured with the toy and the duo soon became inseparable. No parent could ever have imagined then the impact that Jane Goodall as an adult would have on the primate world…

Jane Goodall’s mother was an unusual parent for her time. When five-year-old Jane went missing for hours and turned out to have been hiding in a henhouse conducting her own reconnaissance to discover the origins of eggs, her mother didn’t scold her. She sat down to hear her excited daughter’s discoveries. Similarly, when this small girl in London proclaimed that she wanted to go to Africa to see wild animals and write about them, her mother was encouraging.

As it turns out, Jane’s mother ended up travelling with her on her first expedition to Africa, as even as a 26-year-old in 1960, it wasn’t considered appropriate for a young lady to be travelling alone. The research Jane Goodall conducted in Gombe, Africa was groundbreaking on many levels. Just one breakthrough was the way that, despite being told she wouldn’t get close to wild chimpanzees, Jane was soon handing certain individuals bananas. This close observation uncovered many surprising learnings.

Jane’s 1963 article for National Geographic reports her initial findings, but in a way which could just as well be describing her human neighbours as her primate ones. The trajectory of her friendship with David Greybeard, the first chimpanzee she handed a banana to, is one such story. Each chimpanzee has its own name, and Jane an acute understanding of their personalities.

While perhaps not reported in the fashion in which the scientific community at the time thought appropriate (she was criticised for giving the chimpanzees names instead of numbers), there was no denying her findings were new and very valuable. Jane famously first discovered chimpanzees using tools – a skill which, until that time, had been considered uniquely human. She also discovered that chimpanzees would adopt the young of others, that they participate in warfare, sometimes for years, and that, although chimpanzees are considered vegetarians, they actively hunt and eat other animals on occasion.

Contrary to many in her field, Jane insists primates are very similar to humans in terms of what we call ‘feelings’. “Chimpanzees show emotions that are similar or identical to those that we call happiness, sadness, fear, despair and so on. Strong, affectionate and supportive bonds that develop among family members can last a lifetime of 60 years or more,” she reflects.

Goodall’s research has continued in Gombe since that first connection in 1960. “Fifty years since I first began my research at what is now Gombe National Park, we are still learning about the chimpanzees there. The Gombe research program is one of the longest running studies of animals in the wild, providing insights into our closest relatives’ emotions, behaviours and social structures. There is still much data from the past to be analysed and much more research to be conducted on the offspring of the chimpanzees that I originally studied.” The research covers a range of scientific disciplines, including evolution, ethnology, anthropology, behavioural psychology, sociology, conservation, disease transmission and aging. “I could go on and on about the research’s impact. The great apes still have so much more to teach us, as do many other animals, which is why it is so critical to address the threats to their survival and save these and other endangered creatures.”

Around the turn of last century, about one to two million chimpanzees lived in African forests. Today’s estimates are less than 300,000. Through habitat loss and bushmeat hunting, the chimpanzee’s numbers have been drastically reduced. “Right now, the chimpanzees of Gombe National Park are isolated on a narrow stretch of intact forest. Outside this corridor, the forests have been largely eliminated and the land is being used in unsustainable ways for agriculture and as living space for an exploding human population that lacks basic needs,” Jane explains. “The Jane Goodall Institute (JGI), which I founded in 1977, has several programs in Africa that address this loss of habitat. These include our program called TACARE (pronounced ‘take care’), which began in 1994. TACARE seeks to address the rapid degradation of natural resources in the area by focussing on community socio-economic development and offering training and education in sustainable natural resource management. Working in 24 villages near Gombe National Park, TACARE offers information on sustainable farming methods and hybrid higher-yield crops. Through its forestry initiative, it has created more than 100 tree nurseries, provided more than 750,000 trees and restored habitats around the park. In addition, TACARE has helped villages establish their own small loan [microfinance] programs and provides scholarships for girls, and family planning and HIV/AIDS education. These are Tanzanian programs run by local people and they work!”

The program is working so well that it has been extended to include the entire Gombe ecosystem, and an area to the south of Gombe. “We have engaged roughly 25 additional villages to the south in broad scale land-use planning; sharing information we have developed using state-of-the-art satellite technology. You see, the people living around Gombe need the forest, and regenerating the forest is beneficial to addressing climate change. And while the programs which are aimed at education, clean water, sanitation and so forth enable villagers to regenerate the forest, they also create more stable and healthy communities on a continent that has seen too much civil unrest and the transmission of infectious diseases. Needless to say, we’re really proud of our comprehensive approach to conservation and are replicating it in other parts of Africa.”

In 1999, the institute created an 18,000 acre reserve alongside Tchimpounga, a 65 acre sanctuary site in the Republic of Congo. In addition to reserving habitat for wildlife, the program provides education to raise residents’ environmental awareness. “We also employ local ecoguards to protect the area against poachers,” says Jane. “We have found that, if we address poverty and improve the lives of people residing in and around chimpanzee habitats in an environmentally sustainable way, we can better protect and preserve the remaining forests and their inhabitants. I see our comprehensive approach to conservation as a model and as the way forward.”

Whilst Jane still oversees research and education programs in Gombe, she realised long ago that her own time would be better invested in advocacy abroad rather than on the ground in Gombe. She now travels approximately 300 days per year, sharing her story and her vision for chimpanzees and humanity. She opens many talks with a chimpanzee greeting: a sound she is very familiar with, yet is foreign to many people. The sight of this well-groomed woman making animal noises could be absurd, but it is always moving, and sometimes haunting.

All up, Jane balances her environmental concerns with an inspiring sense of hope. “In spite of all the terrible things going on in the world, I do have hope. And my hope is based on three factors,” she explains. “First, we have at last begun to understand and work to solve the problems that threaten the survival of life on Earth. We can use our problem-solving abilities, our brains, and by joining hands around the world find ways to live in harmony with nature. Millions of people around the world are beginning to realise that we all have a responsibility to our environment and that every action we take, every day, makes a difference!

Millions of people around the world are beginning to realise that we all have a responsibility to our environment and that every action we take, every day, makes a difference!

“My second reason for hope lies in the tremendous energy, enthusiasm and commitment of a growing number of young people around the world. As they learn about the various environmental and social problems facing the planet, they want to change things and right the wrongs. Of course they do. They have a vested interest in this as they will inherit this world one day. They will be moving into leadership positions, into the workforce and become parents themselves. Young people, when informed and empowered, when they realise that what they do truly makes a difference, can indeed change the world.

“My third reason for hope lies in the indomitable nature of the human spirit. There are so many people who have dreamed seemingly unattainable dreams and, because they never gave up, achieved their goals against all the odds, or blazed a path along which others could follow. As I travel around the world I meet so many incredible and amazing human beings. They inspire me. They inspire those around them.”

At the end of the day, it’s the emotions that Jane Goodall has so often observed in human beings and chimpanzees alike which she sees as the key to a better future. “Without hope, all we can do is eat and drink the last of our resources as we watch our planet slowly die. Instead, let us have faith in ourselves, in our intellect, in our staunch spirit. Let us develop respect for all living things. Let us try to replace impatience and intolerance with understanding, compassion and love.”

Let us try to replace impatience and intolerance with understanding, compassion and love.

JANE GOODALL’S CAMPAIGNS

Roots & Shoots

“If we can involve young people, especially those from 18 to 24, who are going out in the world as the next politicians, the next lawyers, the next doctors, the next teachers, the next parents – then perhaps we create a critical mass of youth that have a different set of values. This is why Jane Goodall’s Roots & Shoots, the Jane Goodall Institute’s global humanitarian youth program, is so important to me.”

The program was started in 1991 and now brings together hundreds of thousands of members in more than 120 countries. Roots & Shoots provides a framework for young people to form groups and work on three projects. One project focuses on their community reaching out to other communities. The second project is for animals including domestic animals, and the third for the environment.

www.rootsandshoots.org

They’re calling on you

“Each time a mobile phone rings, coltan, a tiny piece of metallic ore from Africa, is making the call possible. The illegal mining of coltan within the Congo River Basin is contributing to forest loss and unrest in the region and is accelerating the loss of gorillas at an alarming rate.”

Jane launched the They’re Calling on You mobile phone recycling campaign in October 2008 at Melbourne Zoo. The campaign recycles mobile phones, diverting waste from landfill, reducing the demand for coltan and raising funds for the zoo’s conservation programs and the Jane Goodall Institute. Zoos all over Australia are now involved in the program together with over 150 organisations and 100 schools. More than 164,000 mobile phones have been collected raising over $271,000 for conservation.

“The component raised for the Jane Goodall Institute through the campaign has all gone directly to feed, clothe and buy equipment for Park Rangers at the Maiko National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo. These men are risking their lives to save these gorillas, but also in the Park they are also protecting chimpanzees, forest elephants, okapi and a huge variety of other mammals, birds, reptiles and insects.”

www.zoo.org.au/calling_on_you