Art Imitates Leaf: Immerse Yourself In Nature at the ‘Entwined: Plants and People’ Exhibition

Plant life: more than just a hashtag, our connections to our leafy pals go way back. Especially as the world continues to change around us, it’s become even more important to pause, breathe and connect with the natural world. Exploring our intrinsic relationship with plants through photography, illustrations, immersive projections and historical objects is the State Library of Queensland’s latest exhibition, Entwined: plants and people. Running through to Sunday 14 November, we caught up with curator and specialist librarian Joan Bruce to learn a little bit more about the free exhibition and the undeniable power of plants.

image (left to right) Illustration of a bunya cone in Flore des serres, 1875; Sydney Parkinson’s illustration of Banksia integrifolia from Banks’ Florilegium, 1983; Rosa Fiveash’s illustration of Pittosporum angustifolium from Forest Flora of South Australia, 1882. All courtesy of State Library of Queensland.

Tell us about the exhibition? What inspired it?

The original idea goes back almost a decade. We were planning an exhibition to showcase the extraordinary botanical illustration in State Library of Queensland’s collection – works like the Banks’ Florilegium. When the idea re-emerged in 2019, the scope was broadened to cover a much wider range of stories; contemporary as well as historical. We expanded upon the human connection to plants including connection to Country, stories of science, as well as art, and the practical uses of Queensland plants by First Nations peoples.

How can art help us understand plants and work towards a more sustainable future?

Many people in urbanised societies are disconnected from the natural world. Some people call this ‘green blindness’. Art can bridge that disconnect and help you to see the world of plants. One of the first works you see when you enter Entwined is a video installation by local artists Man&Wah. This immersive experience slows you down. You can feel the stress sliding off your shoulders. This is one way artists can help us understand plants – by feeling the pleasure of connection with the natural world. Donna Davis, another local multi-disciplinary artist, works in the area where art meets science. Her artwork is visually intriguing, but there’s a strong ecological message if you look more closely. The animated plant critters roaming all over State Library at the moment came out of her residency with a tropical mountain plant rescue project in North Queensland. These are some of the species at risk from climate change, plants which live in the cloud forests above 1000 metres.

What is the relationship between plant studies and the arts?

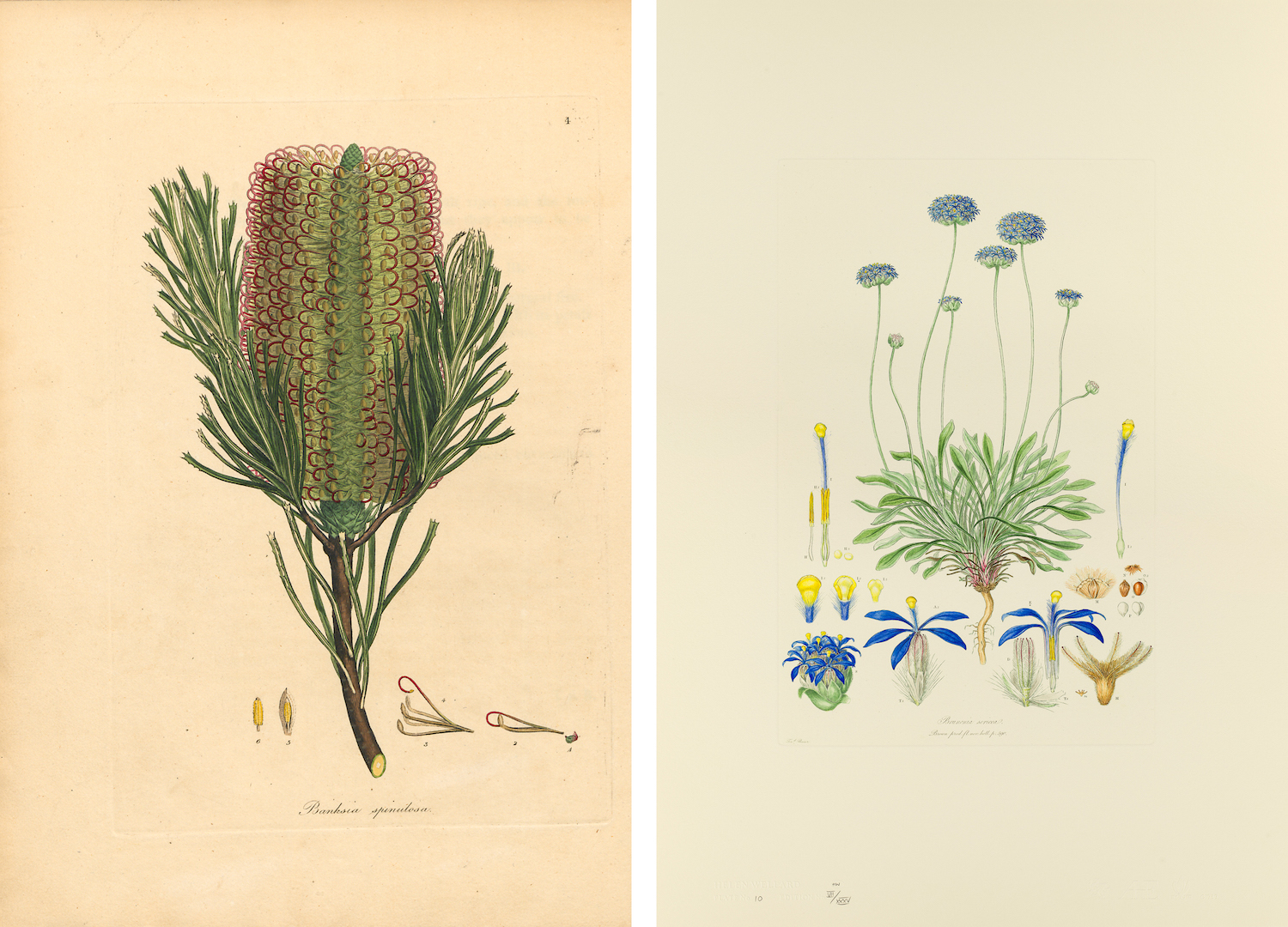

One area where art meets botany is in scientific botanical illustration. Entwined features the work of three of the greatest botanical illustrators of all time: twentieth century Australian artist Celia Rosser and eighteenth century artists James Sowerby and Ferdinand Bauer. In the twenty first century, herbariums and botanical gardens use art to communicate their message by offering residencies to artists like Donna Davis.

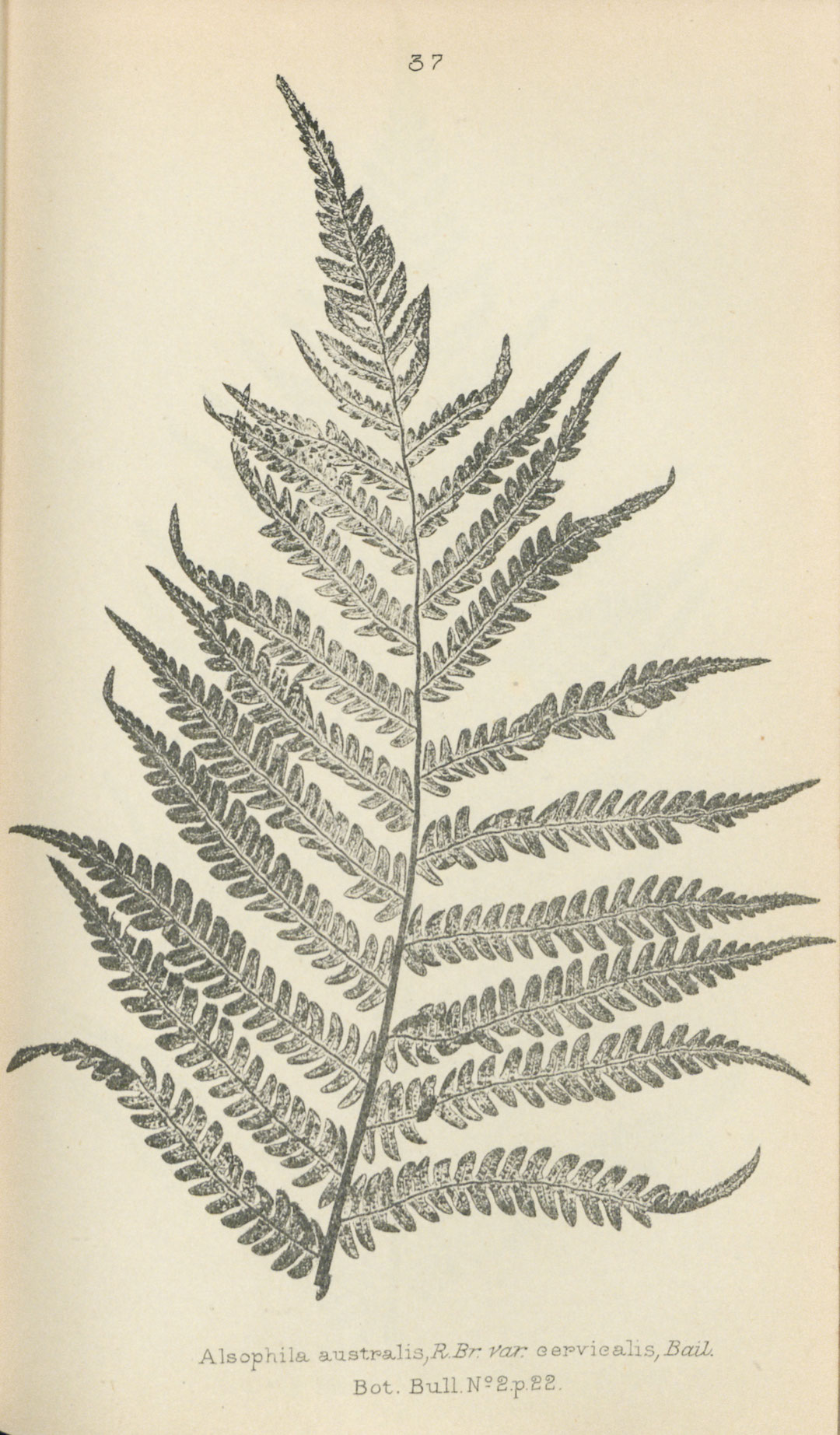

image Nature print from Lithograms of the ferns of Queensland, 1892. Courtesy of State Library of Queensland.

What is your favourite story that has come to light from curating the exhibition?

I am rather fond of the ‘nature printing’ story. Nature printing was cutting-edge technology in the second half of the nineteenth century. It’s basically a process where the plant itself is used to create an illustration, bypassing the need for botanical artists and engravers. At its simplest, you take something like a fern leaf, apply pigment, and press it onto a surface. But that’s only good for one or two, maybe six prints at the most. In the nineteenth century, ways were developed to make an actual printing plate from the plant. The specimens were often pressed between a lead plate and one of harder metal so the grass left an impression in the soft lead. It gets complicated after that, but an essential part of the process was electrotyping the plate.

Our quest for examples of the very latest form of botanical illustration, microscopy, came together at the end of 2020 with University of Queensland research into the infamous Gympie Stinger [a shrub in the nettle family]. Professor Irina Vetter and her team isolated the neurotoxin which causes its ferocious sting, a whole new family of toxins which are surprisingly similar to those of spiders and cone snails. As a result, we were able to tell almost the whole history of botanical illustration through one plant – from an eighteenth century Banks’ Florilegium copperplate engraving, through a watercolour painting by Ellis Rowan to Scanning Electron Microscope photographs of the needles which inject the toxin.

image (left to right) Banksia spinulosa by James Sowerby, 1793. Courtesy of State Library of Queensland; Ferdinand Bauer’s painting of a blue pincushion flower. Courtesy of Natural History Museum.

What do you hope people come away from the exhibition feeling?

Entwined has something for everyone, beautiful art works and many stories for the curious mind. It’s also an experience of the senses. More than anything, I hope people come away full of the pleasure of immersing themselves in the natural world. It’s a timely reminder of how essential plants are to our survival – without them there would be no food to eat or even air to breathe. It’s free, so you can come back whenever you need another healing experience.