So You Want to be a Citizen Scientist? Why Not Forge a New Relationship with Fungi

- Words by Peppermint

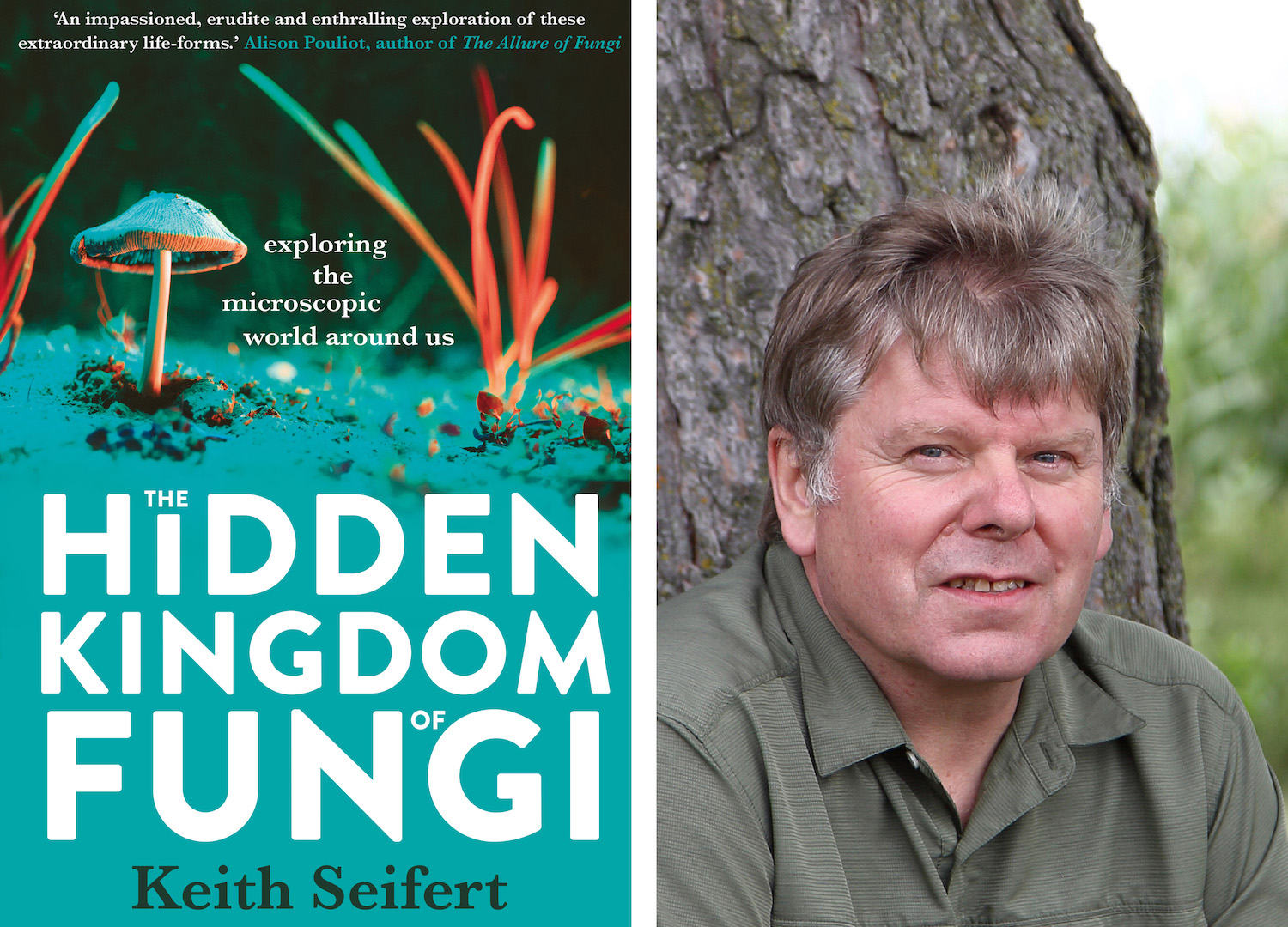

words KEITH SEIFERT photos UNSPLASH

Esteemed mycologist Dr Keith Seifert loves fungi. And fair enough. They’re essential to life on Earth – from releasing the carbon in plants to that delicious umami flavour we can’t get enough of. Revealing this world and all of its beautiful complexity in his latest book, The Hidden Kingdom of Fungi, here Keith posits how amateur naturalists can contribute to our knowledge of the world’s biodiversity and shares some of the things you can do to future-proof the biodiversity of your area.

Without realising it, some people already know quite a lot about fungi. Orchid growers, for example, quickly learn about mycorrhizae because without them they would have no orchids. Out of necessity, gardeners learn about plant diseases and how to avoid them. People who make bread get interested in sourdough starters. Homebrewers experiment with different strains of yeast. Anyone with access to a computer, a mobile phone and its camera, and an internet connection can take advantage of many of the scientific advances that have let us peer deeper into the microbial world.

Anyone with access to a computer, a mobile phone and its camera, and an internet connection can take advantage of many of the scientific advances that have let us peer deeper into the microbial world.

For a few hundred dollars you can purchase a pretty nice microscope with a built-in camera and start to document the microbes in your neighbourhood. You can even send specimens to commercial services and buy a DNA barcode. Contributing fresh observations and data to science is no longer restricted to people with PhDs in industry and academia – we can all take part.

Increasingly, citizen scientists – regular, everyday people in cities and rural communities around the globe – are documenting the biodiversity of their own surroundings and sharing it on digital platforms like the iNaturalist website and mobile app. You can upload photographs (with the GPS coordinates, time and date embedded in the image files), and the artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms will suggest the identity of the organism in the picture. The iNat community of specialists, both amateur and expert, check the results. After two people have confirmed the identification, it is considered “research grade” and a dot is added to the international map of that species’ distribution. At the moment the system works best for larger animals and plants and some groups of insects. Interest is growing and identifications of larger fungi, like mushrooms, lichens, and polypores, are improving. Special projects, such as time-limited bioblitzes (like the Continental MycoBlitz) or ongoing surveys, unite local, national or international naturalists with common interests, building a solid sense of community. When I travel, I use the app as a portable field guide, and at home, I lurk in the background and try to help people identify their moulds.

In recent years, information about historical specimens and cultures – previously only accessible to specialists through card catalogues and institutional databases – was put online at the behest of the Convention on Biological Diversity. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) database collates the catalogues of the world’s biological collections and complements the information collected by iNaturalist and similar citizen science initiatives. Combined, they show the distribution of species as verified by professional researchers and as observed by citizen scientists.

When I travel, I use the app as a portable field guide, and at home, I lurk in the background and try to help people identify their moulds.

If a species seems like it might occur in a particular area but we have no specimens or cultures, iNaturalist can mobilise local participants to try to fill the gap. This allows dedicated amateurs, who often become experts without formal academic training, to contribute specimens to public collections and work with taxonomists who can access state-of-the-art technology. New observations and specimens accumulate at an increasing rate, along with knowledge about where species live and what plants or animals they associate with. This enhances molecular detections made in DNA-based surveys. If potential impacts on biodiversity are well understood, they can be balanced against economic concerns when political decisions, such as imposing quarantines, are being made. And if you like, you can look to see when and where in your area you might hunt for a particular fungus – chanterelles, for example. It’s an exciting time. We are learning which species are truly rare and which just appeared that way because only a few specialists were looking for them. Eventually, we should be able to watch distribution maps of fungi shift in the same way we now watch weather patterns. A dispersed community of interested naturalists can monitor species of interest much more effectively than a small number of border officials and field scouts, something that is already happening with invasive plants. The energy of citizen scientists helps to carry knowledge about microfungi gained from the Petri dish back into nature to help find answers to that critical question: “What does it do?”

Apart from wandering in the wilds, there are other ways you can enjoy the benefits of the mycelial revolution. If you have a garden, growing native plants – which are ideally suited for conditions in your area – helps maintain the integrity of the ecosystem you call home. By cultivating these plants, you also preserve native microbial biodiversity. The mutualistic endophytes and mycorrhizae evolved along with these plants and should also be ideal for your local conditions.

To optimise growth and keep weeds at bay, look for biofertilisers and biocontrol agents at garden centres or online. You can also buy little tins and bags of AM inoculum for flowers and shrubs in your garden. And for your lawn, look for premium grass seed that includes endophytes that protect the plants from hungry insects without having to use insecticides. If you are able, contribute to the Trillion Tree Campaign. This project aims to reduce atmospheric carbon by locking it away in the cellulose and lignin of a trillion newly planted trees. One of the founders is a mycorrhizal researcher. The success of this initiative will depend on endophytes and ectomycorrhizae, of course. Eventually, the project will also benefit the wood decay fungi, but preferably after a few centuries pass and we have more leeway with our carbon budget.

Excerpt from The Hidden Kingdom of Fungi by Keith Seifert (UQP, 2022), out now at all good bookshops and online.

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Brighten up your inbox with our not-too-frequent emails featuring Peppermint-related news, events, competitions and more!

explore

More articles

It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas…. Which means we are officially entering party season. Work parties, friend-dos, family get-togethers and then we’re straight…

Hang out with us on Instagram

Calling all sewists! 📞

Have you made the Peppermint Waratah Wrap Dress yet? Call *1800 I NEED THIS NOW to get making!

This gorgeous green number was modelled (and made) by the fabulous Lisa of @Tricky.Pockets 🙌🏼

If you need a nudge, @ePrintOnline are offering Peppermint sewists a huge 🌟 30% off ALL A0 printing 🌟 when you purchase the Special Release Waratah Wrap Dress pattern – how generous is that?!

Head to the link in bio now 📞

*Not a real number in case that wasn`t clear 😂

#PeppermintWaratahWrapDress #PeppermintPatterns #SewingPattern #WrapDress #WrapDressPattern

8 Things to Know About January 26 - from @ClothingTheGaps:

Before you celebrate, take the time to learn the truth. January 26 is not a day of unity it’s a Day of Mourning and Survival for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It marks the beginning of invasion, dispossession, and ongoing colonial violence. It’s time for truth-telling, not whitewashed history.

Stand in solidarity. Learn. Reflect. Act.

✊🏽 Blog written by Yorta Yorta woman Taneshia Atkinson.

🔗 Link in bio of @ClothingTheGaps to read the full blog

#ChangeTheDate #InvasionDay #SurvivalDay #AlwaysWasAlwaysWillBe #ClothingTheGaps

As the world careens towards AI seeping into our feeds, finds and even friend-zones, it`s becoming increasingly hard to ignore.

We just wanted to say that here at Peppermint, we are choosing to not print or publish AI-generated art, photos, words, videos or content.

Merriam-Webster’s human editors chose `slop` as the 2025 Word of the Year – they define it as “digital content of low quality that is produced usually in quantity by means of artificial intelligence.” The problem is, as AI increases in quality, it`s becoming more and more difficult to ascertain what`s real and what`s not.

Let`s be clear here, AI absolutely has its place in science, in climate modelling, in medical breakthroughs, in many places... but not in replacing the work of artists, writers and creatives.

Can we guarantee that everything we publish is AI-free? Honestly, not really. We know we are not using it to create content, but we are also relying on the artists, makers and contributors we work with, as well as our advertisers, to supply imagery, artwork or words created by humans. AI features are also creeping into programs and apps too, making it difficult to navigate. But we will do our best to avoid it and make a stand for the artists and creatives who have had their work stolen and used to train AI machines, and those who are now losing work as they are replaced by this energy-sapping, environment-destroying magic wand.

Could using it help our productivity and bottom line? Sure. And as a small business in a difficult landscape, that`s a hard one to turn down. We know other publishers who use AI to write stories, create recipes, produce photo shoots... but this one is important to us.

`Touch grass` was also a Merriam-Webster Word of the Year. We`ll happily stick with that as a theme, thanks very much. 🌿

If your fingers are twitching for some crafting, take a peep at this massive list of marvellous makes that can be whipped up in a flash, put together by our Sewing Manager Laura. Ok yes, it was originally a roundup we created for easy Christmas gifts, but now it can be your blueprint for easy craft wins to go on your 2026 making must-do list!

If money and time are slim for you right now – as they are for many of us – these 22 projects will help you avoid the chaos and consumerism of the malls, scratch that creative itch and produce a fun me-made make that won’t break the bank.

Link in bio! 🪡🎨✂️

#PeppermintMagazine #MeMadeGifts #DIYs #EasyWins

"I, like so many of my fellow sewists, live a life of endless lists of ‘to-sew’ patterns, fabrics and garments. My stitchy to-do list is longer than my arm and it ain’t getting any shorter. There are just so many wonderful surface pattern designers, indie pattern-makers and small businesses who I want to support, that I am simply never short of inspiration for garments I’d like to sew. But you know what just does not seem to make its way to the top of the list? Pyjamas. Jimmy-jams, PJs, jarmies. They just don’t rate highly enough for me to commit time and fabric to them. I mean, barely anyone even gets to see them. The ratio of bang vs buck is low on the ‘thanks-I-made-it-ometer’."

You’ve probably heard it from your Nan: always wear nice undies, because you never know what might happen! (And who might catch a glimpse.) But just in case the unexpected happens while you’re slumming it at home in your washed out tracky dacks, Peppermint sewing manager Laura Jackson’s adding pretty PJs to her list of preferred ‘ghost outfits’… Because shuffling off this mortal coil can be perfectly stylish, too.

Read more of `Haunt Couture: Why Laura Jackson Decided To Up Her Pyjama Game` at the link in our bio!

Words and photos: @Laura_The_Maker 💤

#PJPatterns #MeMadePJs #Pyjamas #GhostOutfit

STAY SOFT ☁️

We love when some of our friends collide! And this collab between @SueChingLascelles and the legends at @DangerousFemales is a goodie.

From Sue-Ching:

New year, new mantra babes, because we tried being tough and it was exhausting. So now we’re going to lead with kindness and compassion and see what happens. We have nothing to lose! So let’s stay soft this year. Love ourselves and each other.

New limited edition tee designed by me for @DangerousFemales. 100% of the profits go to supporting DV services. Available NOW and did I mention limited edition? Such a cutie reminder for the year we’re going to have. The year we deserve to have.

BIG LOVE ya big SOFTIES 🤍

Sue-Ching x

Photos by @AMRPhotographer_

#DangerousFemales #DVAwareness #StaySoft