Shine On – We’re Feeling Summer Ready with the Release of Issue 60

- Words by Peppermint

words KELLEY SHEENAN, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

The Britannica Dictionary describes a diamond in the rough to be “a person who has talent or other good qualities but who is not polite, educated, socially skilled, etc”. As we hit 60 issues (and loosely borrow the diamond jubilee symbolism for this milestone without the monarchist implications), this description feels apt of Peppermint>’s beginnings (and likely myself).

Grammarist goes on to say that there is a similar Japanese saying, tama migakasareba hikari nashi, which translates as ‘a jewel, unless polished, will not sparkle’. The last 15 years have seen my precious, rough gem be tumbled, cut and polished by all the brilliant people who have worked with me to make it what it is today.

A diamond itself does not shine; its sparkle is the result of three things: reflection, refraction and dispersion. To put it simply, the light enters, is bounced around and is then sent out into the world as an array of rainbow colours. Much like how I have always seen the pages of this magazine – a vehicle for the brilliance around us.

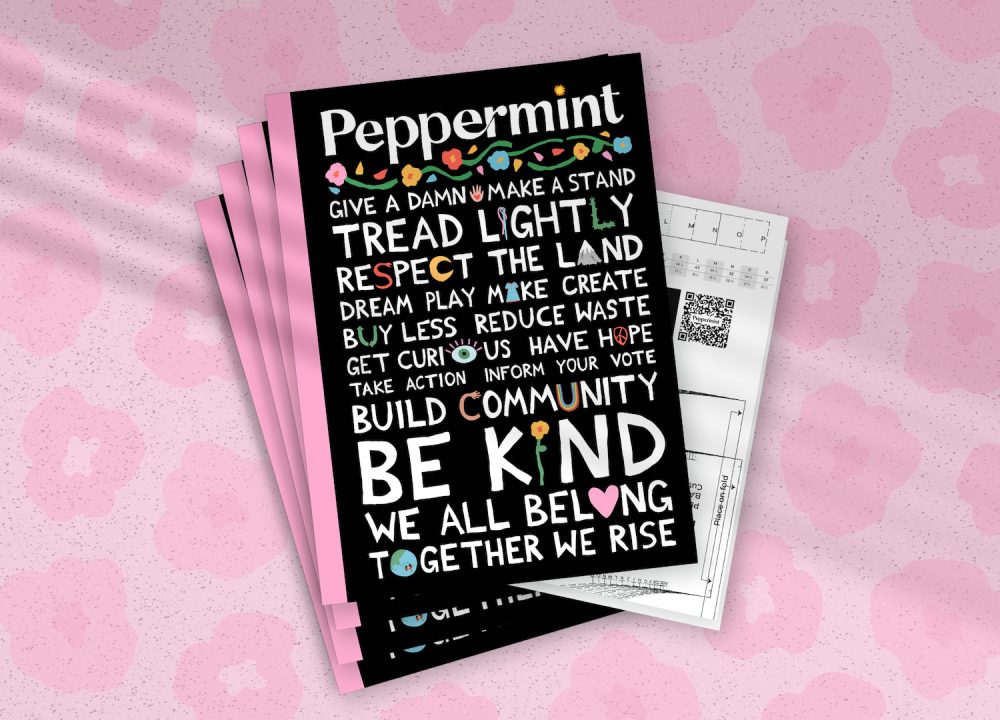

We wanted Issue 60’s special cover to shout to the world what our values are, what we care about and what we think matters. A manifesto of sorts. Luke John Matthew Arnold brought our carefully crafted words to life beautifully, words that we hope resonate with you too and inspire you to make change. Those changes can begin at home, with friends, family, your workplace, your community – and of course, ultimately – your world. I hope you find your own light to shine bright, and remember as Rihanna sang: “We’re beautiful like diamonds in the sky.”

– Kelley x

Subscribe (and never miss an issue).

Take a peek inside this issue!

‘PRESS ON’ “What will you be wearing tomorrow? Will your jacket have been grown in a lab, or your jeans coloured using bacteria? Will we still have shops? What does the future of work look like for the people who make our garments?” We explore fashion’s brave new world. Words by Clare Press.

IMAGINE: The fashion world is built on genuine beauty. The appeal of a garment extends right back through the process of making it, whether that’s by skilled hand or sophisticated machine. The people who make our clothes are treated with respect. Materials are regenerative and biodegradable, recycled or upcycled. The fashion industry exceeded its 2030 climate targets, and reached net zero a few years later. It operates safely within planetary boundaries. Sharing and repairing clothes is convenient and inviting. Slow, local fashion is flourishing. But if you prefer, there’s a high-tech digital solution for everything. Apps connect circular fashion services, or you can change your look every hour by dressing your avatar. Greater government regulation means that new clothing from global brands is much more sustainable than it used to be. There is also less of it. We used to pretend that fast fashion was a democratising force, simply because the price points were low. We’ve wised up, and now recognise that value means more than price.

We’ve largely stopped talking about ‘sustainability’ but new words have come into fashion parlance – we link ‘empathy’ and ‘integrity’ to fashion, and consider ‘collective wellbeing’.

Success has been redefined. Companies now prioritise ethical production and purpose as well as profits. There is a new spirit of pre-competitive collaboration. This fairer fashion world is also an inclusive one. Design caters to every body, and fashion celebrates difference. Whether it’s DIY or AI-enabled, we get to play more with personal style. We’ve largely stopped talking about ‘sustainability’ but new words have come into fashion parlance – we link ‘empathy’ and ‘integrity’ to fashion, and consider ‘collective wellbeing’. The razzle dazzle remains – but the guilt is gone, since fashion no longer exploits. It is a positive influence on the planet, on culture, communities and mental health.

‘BREAST IN SHOW’ In 2023, the humble bra can signify many things. For some it’s a necessity; for others a sign of femininity. Some wear one as a means of comfort; some see it as yet another patriarchal tool of objectification. Overall, wearing a bra – and indeed what type of bra you wear – is entirely a personal choice. But it wasn’t always this way. Strap in, folks! We’re deep-diving into the history of the bra. Words by Bonnie Liston.

The humble bra. Brassiere. The ol’ over-the-shoulder boulder holder. The knocker lockers where you store your rack pack. Whatever you call them, they’re an item many of us keep close to our hearts. And not only because they provide necessary structural support for our chests.

As a garment designed to enshroud the breasts – a secondary sexual characteristic societally associated with the gender designated as ‘woman’ – bras hold a great deal of metaphorical significance whether being allegedly set alight by strident feminists or worn in provocative cone shapes by mononymous pop stars.

Bras hold a great deal of metaphorical significance whether being allegedly set alight by strident feminists or worn in provocative cone shapes by mononymous pop stars.

But bras, both the word and the garment we know today, are less than 100 years old, having emerged in the 1930s. Throughout history, however, humanity has turned to various means to restrain and reveal, support and supplement, its boobs. A closer look at this history may reveal to us interesting insights about fashion status, and society, as well as the human creativity and ingenuity that has been applied to buttressing said boobies.

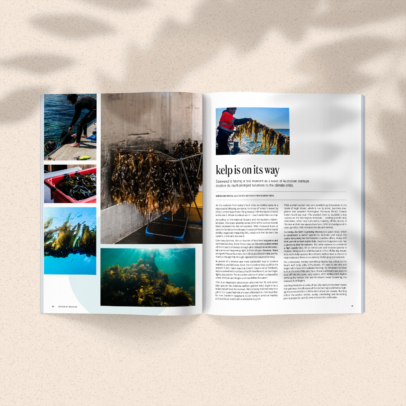

‘KELP IS ON ITS WAY’ Seaweed is having a real moment as a wave of Australian startups explore its multi-pronged solutions to the climate crisis. Words by Haley Kigbo.

As the wakame from today’s hunt dries on clothes racks in a repurposed shipping container, the irony of ‘Winter’s Warm’ by Eddy Current Suppression Ring playing in the background sticks in the mind. Winter is indeed warm – much earlier than normal.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the ocean absorbs about 30% of the carbon dioxide that’s released into the atmosphere. With increased levels of carbon dioxide come changes in ocean pH levels and increased acidity, negatively impacting fish, corals and shell builders like oysters, crabs and sea snails.

The irony of ‘Winter’s Warm’ by Eddy Current Suppression Ring playing in the background sticks in the mind. Winter is indeed warm – much earlier than normal.

Like many farmers, the co-founder of Southern Seagreens and commercial diver, Brent Cross, says you become acutely aware of the impacts of climate change when disruptive environmental events are happening right in front of you. However, Brent along with his co-founders, Cam Hines and Rob Brimblecombe, want to change that through regenerative seaweed farming.

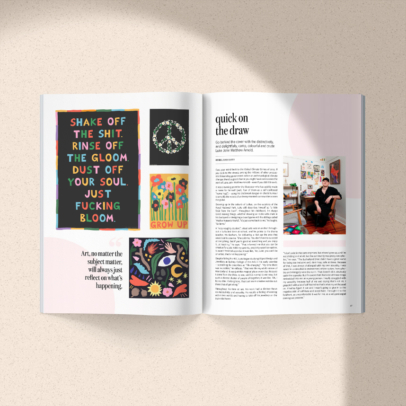

‘QUICK ON THE DRAW’ Go behind the cover with the distinctively, and delightfully, camp, colourful and crude Luke John Matthew Arnold. Words by Lauren Baxter.

Cast your mind back to the Global Climate Strikes of 2019. If you took to the streets among the millions of other protesters demanding government action on anthropological climate change, there’s a good chance you might have come across the work of Luke John Matthew Arnold – even if you didn’t know it.

It was a turning point for the illustrator who has quickly made a name for himself (well, four of them as a self-confessed “name hog”) – using his trademark tongue-in-cheek humour to amplify the voices of underrepresented communities across the globe.

You don’t have to succeed at everything, but if you’re good at something and you enjoy it, at least try.

Growing up in the suburb of Loftus, on the outskirts of the Royal National Park, Luke still describes himself as “a little feral from the bush”. Throughout his childhood, he always loved making things, whether drawing on rocks with chalk in his backyard or designing a board game with his siblings called ‘Mother Nature’s World’. “It’s just come back to me,” he laughs. “So lame.”

A “very naughty student”, visual arts was an anchor throughout a turbulent time at school, and he points to his drama teacher, Ms Gorham, for delivering a kick up the arse that would set his course. “She told me, ‘You don’t have to succeed at everything, but if you’re good at something and you enjoy it, at least try,’” he says. “That informed me that you can be creative for a job. With my parents, creativity wasn’t an option. It wasn’t frowned upon but it was like, ‘No, Luke, you can’t be an artist, that’s not happening.’”

‘BY A WHISKER’ He’s spent the past ten years of his life dedicated to their protection. But marine biologist Dirk Holman needs help to save the Australian sea lion. Words by Harriet Spark.

In the rugged and wild Great Australian Bight, at the base of plunging sandstone cliffs where the desert meets the sea, lives one of the rarest marine mammals on Earth – the Australian sea lion.

But these adorable ‘puppies of the sea’ face an uncertain future due to decades of overfishing, habitat destruction and anthropological climate change, and one marine park ranger, Dirk Holman, has devoted his life to turning the situation around.

He realised their populations were declining rapidly, and they urgently needed help.

Growing up in the small coastal town of Port Lincoln, Dirk spent his youth surfing along South Australia’s coastline. It’s home to the largest commercial fishing fleet in the southern hemisphere, and after finishing high school, Dirk started working on these boats. Unsurprisingly, fishermen who have witnessed the threats facing our oceans firsthand can often become some of the fiercest marine advocates, and at 28, Dirk decided to switch career paths and enrolled in a marine biology degree.

Dirk moved to Coffin Bay, on the southern tip of the Eyre Peninsula, to raise a family and began work as a marine park ranger. He had plans to complete a PhD on great white sharks but after doing a stint of fieldwork monitoring colonies of Australian sea lions, he realised their populations were declining rapidly, and they urgently needed help.

‘VISIBILITY IS POSSIBILITY’ Appearance activist Carly Findlay rewrites a childhood yearning for disabled representation with her own seven icons. Words by Carly Findlay.

When I was a kid, I used to put posters of my idols on my bedroom walls – pop stars, actors, models, even a cricketer! I wanted to know everything about them – and dreamed of becoming a journalist so I too could write articles about my idols. I looked to them to show me what was possible. But none of them were disabled… yet I was.

Although I have lived with ichthyosis, a severe rare skin condition, since birth, I didn’t identify as disabled until I came to know other disabled people and saw how much we had in common. While I had a different diagnosis, we experienced similar barriers – inaccessible spaces, discrimination and significant time off work and school because of illness, and hospital appointments and stays. I also admired the strong sense of pride many of the disabled people I came to know had.

I would have been reassured that I could lead both an ordinary and extraordinary life.

If I had known more disabled people when I was younger, I would have found disability pride sooner. I would have seen that disability isn’t shameful or limiting. I would have been reassured that I could lead both an ordinary and extraordinary life.

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Brighten up your inbox with our not-too-frequent emails featuring Peppermint-related news, events, competitions and more!

explore

More articles

Look, I don’t want to make anyone panic but IT’S DECEMBER!!! If you’re planning to give homemade gifts, you’re going to have to act fast. …

Hang out with us on Instagram

🌻 The Paddington 🌻

This is a much-loved staple, created for Issue 50 in 2021. We love seeing the #PeppermintPaddingtonTop continually popping up in our feeds!

How stunning is our model Elon MelaninGoddessEfon – she told us it was one of the first times she had been asked to come to a shoot with her natural hair. 🌻

We worked with South African patternmaker Sarah Steenkamp of @FrenchNavyNow_ to create this wardrobe essential – the perfect puff-sleeve blouse. Raglan sleeves make it the ultimate beginner sew, plus the gorgeous back buttons let you add your own personal twist.

Pattern via the link in bio! 🪡

Photos: @KelleySheenan

Fabric: @Spoonflower

Model: MelaninGoddessEfon

“In the 1940’s, Norwegians made and wore red pointed hats with a tassel as a form of visual protest against Nazi occupation of their country. Within two years, the Nazis made these protest hats illegal and punishable by law to wear, make, or distribute. As purveyors of traditional craft, we felt it appropriate to revisit this design.”

Crafters have often been at the heart of many protest movements, often serving as a powerful means of political expression. @NeedleAndSkein, a yarn store in Minnesota, are helping to mobilise the craftivists of the world with a ‘Melt The Ice’ knitting pattern created by @Yarn_Cult (with a crochet pattern too), as a way of peaceful protest.

The proceeds from the $5 pattern will go to local immigrant aid organisations – or you can donate without buying the pattern.

Raise those needles, folks – art and craft can change the world. 🧶

Link in bio for the pattern.

Images: @Gather_Fiber @NeedleAndSkein @a2ina2 @KyraGiggles Sandi.204 @WhatTracyMakes AllieKnitsAway Auntabwi2

#MeltTheIce #Craftivism #Knitting #CraftForChange

TWO WEEKS TO GO! 🤩

"The most important shift is moving from volume-led buying to value-led curation – choosing fewer, better products with strong ethics, considered production and meaningful stories. Retailers have real influence here: what you buy signals what you stand for. At Life Instyle, this means using the event to discover and invest in small-scale, planet-considerate brands that align with your values and your customer’s conscience. Consumers don’t need more things; they need better things, and retailers play a key role in selecting, contextualising, and championing why those products matter."

Only two more weeks until @Life_Instyle – Australia`s leading boutique retail trade show. If you own a store, don`t miss this event! Connect with designers, source exquisite – and mindful – products, and see firsthand why this is Australia’s go-to trade show for creatives and retailers alike. And it`s free! ✨️

Life Instyle – Sydney/Eora Country

14-17 February 2026

ICC, Darling Harbour

Photos: @Samsette

#LifeInstyle #SustainableShopping #SustainableShop #RetailTradeEvent

Calling all sewists! 📞

Have you made the Peppermint Waratah Wrap Dress yet? Call *1800 I NEED THIS NOW to get making!

This gorgeous green number was modelled (and made) by the fabulous Lisa of @Tricky.Pockets 🙌🏼

If you need a nudge, @ePrintOnline are offering Peppermint sewists a huge 🌟 30% off ALL A0 printing 🌟 when you purchase the Special Release Waratah Wrap Dress pattern – how generous is that?!

Head to the link in bio now 📞

*Not a real number in case that wasn`t clear 😂

#PeppermintWaratahWrapDress #PeppermintPatterns #SewingPattern #WrapDress #WrapDressPattern

8 Things to Know About January 26 - from @ClothingTheGaps:

Before you celebrate, take the time to learn the truth. January 26 is not a day of unity it’s a Day of Mourning and Survival for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It marks the beginning of invasion, dispossession, and ongoing colonial violence. It’s time for truth-telling, not whitewashed history.

Stand in solidarity. Learn. Reflect. Act.

✊🏽 Blog written by Yorta Yorta woman Taneshia Atkinson.

🔗 Link in bio of @ClothingTheGaps to read the full blog

#ChangeTheDate #InvasionDay #SurvivalDay #AlwaysWasAlwaysWillBe #ClothingTheGaps

As the world careens towards AI seeping into our feeds, finds and even friend-zones, it`s becoming increasingly hard to ignore.

We just wanted to say that here at Peppermint, we are choosing to not print or publish AI-generated art, photos, words, videos or content.

Merriam-Webster’s human editors chose `slop` as the 2025 Word of the Year – they define it as “digital content of low quality that is produced usually in quantity by means of artificial intelligence.” The problem is, as AI increases in quality, it`s becoming more and more difficult to ascertain what`s real and what`s not.

Let`s be clear here, AI absolutely has its place in science, in climate modelling, in medical breakthroughs, in many places... but not in replacing the work of artists, writers and creatives.

Can we guarantee that everything we publish is AI-free? Honestly, not really. We know we are not using it to create content, but we are also relying on the artists, makers and contributors we work with, as well as our advertisers, to supply imagery, artwork or words created by humans. AI features are also creeping into programs and apps too, making it difficult to navigate. But we will do our best to avoid it and make a stand for the artists and creatives who have had their work stolen and used to train AI machines, and those who are now losing work as they are replaced by this energy-sapping, environment-destroying magic wand.

Could using it help our productivity and bottom line? Sure. And as a small business in a difficult landscape, that`s a hard one to turn down. We know other publishers who use AI to write stories, create recipes, produce photo shoots... but this one is important to us.

`Touch grass` was also a Merriam-Webster Word of the Year. We`ll happily stick with that as a theme, thanks very much. 🌿